Alan Wade and Frank Derwent

In this two-part series we examine first the lost art of skepping and its transition to the modern and robust frame hive. To begin we trace the origins and practice of skep operation.

[Note: This article did not quite make the June club newsletter but here it is anyway. These ‘novelty papers’ are planned for publication in The Australasian Beekeeper.]

Basics

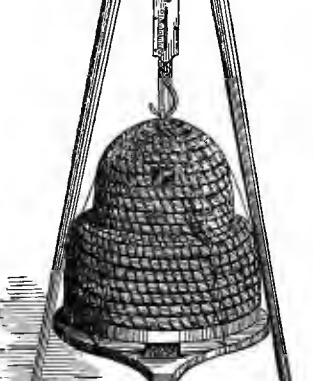

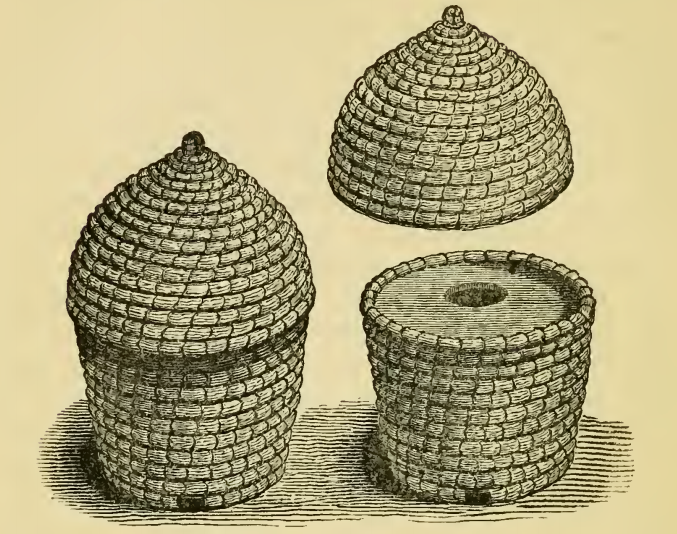

Skepsi, contrived from woven wicker or reeds, or coiled sheathes of straw daubed with mud and animal dung, are ‘bee house baskets’ (Figure 1) placed open-end-down. They date back to Egyptian civilisation some 2400 years agoii.

Figure 1 A 1634 setup of a skepiii

In their simplest form, skeps had a single bottom entrance, their free-formed combs being fixed. Initially, at least, honey and wax could only be obtained by complete destruction of the hive. Like earlier clay pot and log hives they could be neither closely inspected nor could their size be regulated.

Skeppers were and remain skep builders. Many were skilled artisans producing a wide variety of skep designs ranging from simple domes to peaked structures with weather protecting hackles through to flat-topped skeps, over-supered with honey-storing bell glasses or ancillary ‘cap’ chambers made of the same materials as the skeps themselves. Skeps are still used to capture but not keep swarms in.

Skeppists were beekeepers, sometimes equally innovative and also highly skilled employing readily built natural fiber hives.

The origins of skeps and the keeping of bees

Eva Craneiv in her famous books The Archaeology of Beekeeping and The history of Beekeeping and Honey Hunting traces the history of the keeping of bees back to the Egyptians 4400 BP. Over time skep beekeeping (Figure 2) gradually supplanted traditional log (or in the USA black gum, Nyssa sylvatica gum) hives, bark and clay hives, though all these traditions persisted across Europe and North America until as late as the 1960s. Skeps, particularly straw and reed skeps were cheaper to construct than all other hives facilitating their transport to and sale in markets. They were much lighter and less likely to shed their protective and gap filling ‘cow cloome’ required of unsealed wicker skeps.

Figure 2 Middle Ages skeps: and c. 1200v and 1236-c.1250v i

Traditional hives can be viewed as replicas of the natural cavities, tree hollows and rock crevices, that honey bees employ in the wild. Those cavities, providing shelter, allowed honey beesvii to radiate naturally from the tropics to temperate climes where they were insulated from extremes of cold and where they could safely store reserves of honey and pollen that would enable them to survive over the long period of winter dearth. Combs attached to the roof were inaccessible to predators and, in some measure, from the predations of honey hunters whose history goes back to Mesolithic depicted in cave drawings dating back at least 10,000 yearsviii

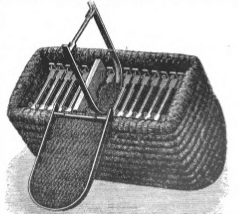

To this day the skep hive symbolises not only the indefatigable bee, but also the industrious and busy beekeeper. The skep also tells the tale of long gone beekeeping practice and, perhaps, the yearnings of beekeepers seeking a more authentic way of making apiculture more sustainable. For a charming accounts of old skep practice see A.H. Bowen’s 1923 account of skep beekeeping in Englandix and Granvenhorts 1907 moveable frame wicker hive (Figure 3) in Germanyx.

Figure 3 Images of Gravenhorts wicker skeps with moveable frames.

It is equally interesting to reflect on the cultural origins of the contemporary inclination of some natural beekeepers to allow bees to swarm freely. Tradition swarming beekeeping was integral to skepping. The practice encouraged bees to swarm and engendering an annual swarm catching frenzy. Very active swarm collection, largely supplanted wild honey hunting, the raiding of natural tree hives often involving tree and hive destruction alike. The list of casualties might have also extended to include the occasional honey hunter misjudging the many hazards of raiding wild bees. In swarm beekeeping, some skeps were deliberately restricted in size to encourage swarming, cast swarms being eagerly chased and watched for much as a nomadic shepherd guarded his flock.

In the skep era large numbers of swarms, equating to plentiful queenright colonies, allowed the progressive establishment of hives until the swarming season was over. The theory was that the more swarms one could collect the more honey one could get. Much of the putative success of swarm beekeeping can be attributed to late season blooms, notably of heather, a time lag that allowed honey bee colonies to build and become populous enough to be reasonably productive. End of season hive destruction was also a factor in encouraging the culture of promotion of swarming driven to produce new replacement colonies and thwarted the natural inclination of bees to survive over winter to become very productive colonies each spring.

In his classic treatise Swarm Control, Geo. S. Demuthxi anticipated swarm prevention, a practice we strongly advocate. It would appear that this message is lost on many contemporary amateur beekeepers:

Gradually methods were devised for the prevention of afterswarms, and systems of management were worked out whereby the actual working force of the colony is not divided by the issuing of the prime swarm. During more recent years methods have been devised by which swarming is either prevented entirely or the act of swarming is anticipated by the beekeeper, which permits the control of swarming without constant attendance. This has made it possible for a beekeeper to operate a series of apiaries without an attendant in each to watch for and hive the issuing swarms.

Since weak hives would not survive winter they were sacrificed as were the most productive hives, the latter so that honey could be harvested. The practice of ‘killing the poor bees’ gradually drew wide-spread condemnation forcing, as we shall see, a good deal of reform and innovation.

So by the early 19th Century skeppists were encouraged to limit hive destruction by preserving medium weight colonies likely to successfully overwinter. Such measures were complemented by skep modification practices that increased the effective size of the skep or which encouraged bees to store more honey.

The art of skep construction is a wondrous and varied tradition. For a glimpse of actual skep making we cannot recommend highly enough the rustic Irish video Hands: Of bees & bee skepsxii.

With the benefit of hindsight, we can now see that skep beekeeping presented two intrinsic problems. Firstly beekeepers could not inspect the comb for diseases and pests. Secondly as, apart from structural bracing, there is no internal structure provided for the bees to attach their combs. Honey combs were attached to the inside of the skep making harvest so difficult that it most often resulted in the destruction of the entire colony.

Skeps were all the rage when we were boys. Way back then keeping bees in skeps was very fashionable. But only thirty of forty years ago, even owning of bees was very much contentious amongst naturalists. Then, though their reward to the agricultural community and our food chain was accepted, they were treated with suspicion as competitors to native birds and insects. We suspect that story has not changed amongst purists though the public sentiment for ‘rescuing bees’ and fervour for actually having a hive certainly has.

Setting up and operating of skeps

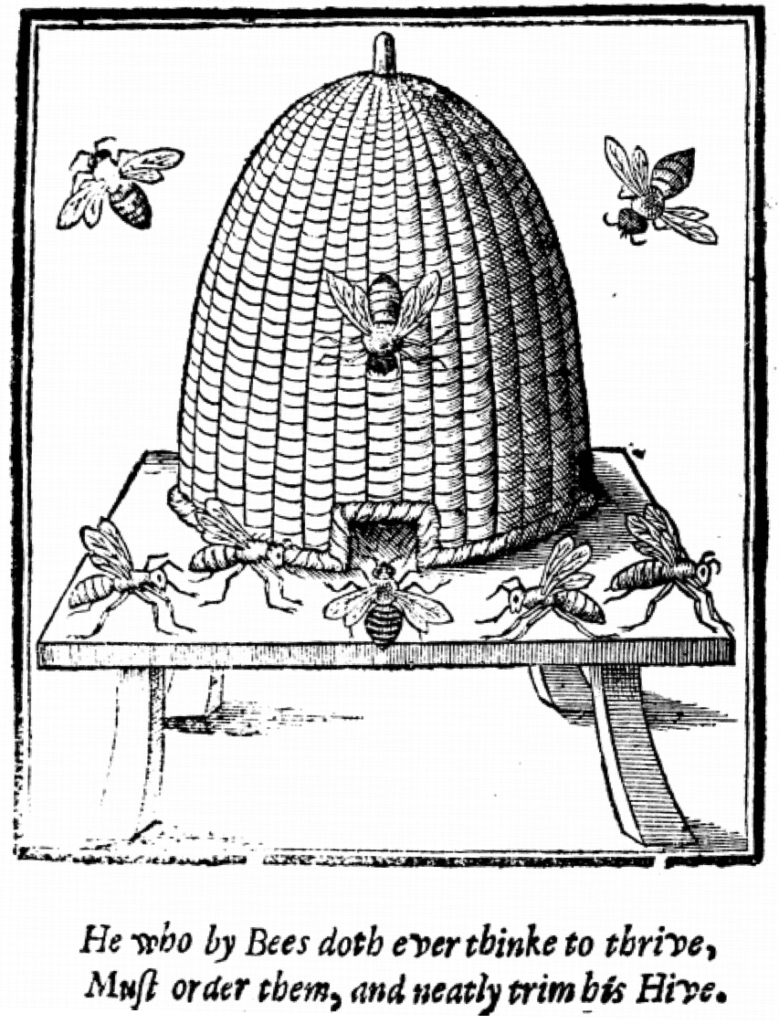

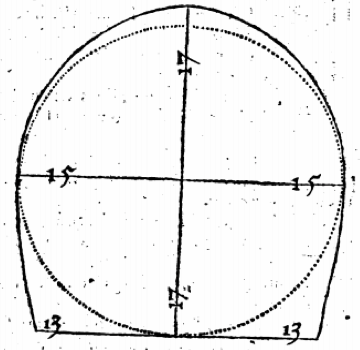

Charles Butler (1609) provides a comprehensive account of skep construction (Figure 4) and operation of skeps in his Feminine Monarchiexiii:

In some countries they use straw hives bound with briar: in some wicker Hives made of Privet, Withy or Hazel, dawbed visually with Cow cloome tempered with gravelly dust, sand or ashes.

The strawne Hives when they are olde and loded, so visually sinke on one side, (specially if they take wet), and so break the combes and let out the hony; and then spleec them strong with a Cop, v. fitted to the top of the Hive.

The Wicker Hives will still be at fault, and lie open, (if they be not often repaired), unto Waspes,Robbers&Mise. Any of these if they find a little chap, will dig her way in: and the Mouse (unless the twigs be close wrought) though she find none.

Both these Hives, if they be not well covered, are subject to wet: which maketh them musty, and if it be much, rotteth the combes, and destroyeth the Bees. But the heat in the Summer, and the cold in the Winter, and the raine at all times doth soonest pierc the Wicker Hives: which is double cause to double dawb them.

All things considered, the strawne Hives are better, specially for small swarmes.

The Bees do best defend themselves from cold, when the hang round together in manner of a Sphere or Globe (which the Philosophers account for the most perfect figure) and the neerer the Hive commeth to the fashion thereof, the warmer and safer the Bees. But of necessitie the bottom must be broad, for the upright and sure standing of the Hive, and for the better taking of the combs: and the top must be rise some two or three inches from then just forme of the Globe, to stay the hackle, and to shunne the raine: which yet, where the hives are covered with panns, is not necessary. Otherwise let your Hives vary no more from this round figure, then needs must, as where it is in the top skirts to the skirts seventeene inches, in the middle or the widest place through the center fifteene inches, and at the skirts thirteene, after this forme.

Hives are to be made of any size between a bushell and half a bushell; that any swarme, of any quantity or time soever, may be fitly hived. v. less than half a bushell will not containe a competent stall; and more than a bushell is found too bigge for any company to continue, and thrive together.

The middling size of three pecks, or within a pottle, under or over, as fitly conteining the naturall quantity of a good stall, is most profitable.

Have alwaies Hives of all sorts (but most of the middling size) in store, lest they be to seeke when you should use them.

The best time for making them, whether they should be Strawne of Wicker, is in the three full moneths of Winter, Sagittar. Capre. and Aquar. v: for then the straw, briers, and twigs are best in season: and then is it best to provide them, because they are best cheape.

Figure 4 Skep dimension instructions: This forme with his dimensions will conteine three pecks: and the abating of one inch in each dimension abateth gawne in the content.

Other detailed instructions are recorded in widely circulated almanacs of good agricultural practice such as those of Edmund Southerne’s 1593 Bee Culturexiv in 1593 in a section on pages two and three entitled ‘The manner how to dresse Hives before you put in Bees’:

…When you have trimmed your Hive, then take Sallow, Willow or Hasell stickes, which being cleft in the middle and cleane shaven, you may put five pearls into a Hive, that is to say, two a crosse foure fingers breadth within side, and the other foure parcels from the top to the mouth, being sticked fast betweene the squares of the cross stickes, is the best way you can splay your Hive, both for ease for the Bees, and also for splaying the Combes within side.

To make a size comparison with the currently used Langstroth eight-frame box in common use, we see that today’s beehives are on the whole larger. An imperial bushel has a volume of thirty six litres, so the recommended skep sizes were between eighteen and thirty six litres: the skep stood approximately 860 mm high and was 760 mm wide at the base.

Our eight-frame box has an internal volume of thirty five litres, quite close to the maximum recommended skep size. It is also approximates the size of wild bee hives remarkably optimised to survive Varroa destructorxv. In practice the set-up volume of a single eight-frame hive will be at least forty litres when allowance is made for migratory lid and bottom board space. For the recommended minimum two-box hive that volume increases to about seventy five litres.

The later invention of keeping bees in sturdy moveable frame hives meant that the colony did not need sulphuring (smoking to death) or drowning of bees to harvest the crop and that advances in queen breeding to produce more tractable and productive bees could be made. To otherwise harvest honey from skeps beekeepers had either to drive the bees out of the skep into a facing empty skep or, by the use of a bottom extension called an eke or a top extension called a cap, create compartments – the predecessor of the honey super – where honey alone was stored.

The driving of bees – drumming them from a mature skep of bees into an empty skep rather than always killing them to harvest honey and wax – was popularised by poet Thomas Tusserxvi in the 1550s.

Driving of hives and preserving of bees

Now burne up the bees that ye mind for to driue,

at Midsomer drive them and save them alive:

Place hive in good ayer, set southly and warme,

and take in due season wax, honie, and swarme.

Set hive on a plank, (not too low by the ground)

where herbe with the flowers may compas it round:

And boordes to defend it from north and north east,

from showers and rubbish, from vermin and beast.

In another Renascence Edition, Tusserxvii advocated the feeding bees to save their lives:

Saint Mihel byd bes, to be brent out of strife:

saint Iohn bid take honey, with fauour of life.

For one sely cottage, set south good and warme:

take body and goodes, and twise yerely a swarme.

At Christmas take hede, if their hiues be to light:

take honey and water, together well dight.

That mixed with strawes, in a dish in their hiues:

They drowne not, they fight not, thou sauest their liues.

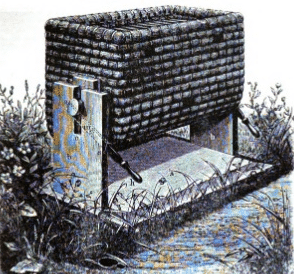

By the middle ages, skep design advanced considerably, notably though the use of ekes or nadirs, typically coils of wreathed straw made into rings (Figure 5) that could be ‘undersupered’ to expand their capacity to store honey.

Figure 5 Eking, imping or nadiring of skeps sometimes using multiple ringsxviii

But as we all know, these advances, with the ready transport of bees, came many maladies. While skep beekeeping did not allow for disease control other than by natural attrition, modern beekeeping has resulted in bee diseases being spread simply by interchanging gear both within and between beekeeping operations. Honey bee queen exports and long distance movement of bees for pollination services has resulted in global disease spread and mixing of the honey bee gene poolxvix, the latter, for example, occasioning the killer bee phenomenon in the United Statesxx. If you are not quite convinced about the unintended impact of free trade on bees, neither chalkbrood nor small hive beetle were even contemplated as problems in Australia thirty years ago. Yet both are now widespread and AFB is far more common and we are set to be affected by the likes of Asian hornets, the African large hive beetle and a suite of arachnid mites. We are reminded an apiary owned by one of the authors that was quarantined following a suspected American Foul Brood outbreak back in the early 1980s. Fortunately turned out to be EFB and all hives recovered.

Skeppists were often skilled and knowledgable beekeepers, more than capable of managing fixed comb hives far better than the many present day back yarders who own but who largely neglect their bees. If you have any doubt about the skilled art of skepping, we strongly recommend you watch the late 1970’s videoxxi of a 700-strong skep bee yard in NW Germany. It demonstrates the remarkable understanding of the swarm issuing season, the capturing and mating of virgin queens, skep surveillance to both unite swarms and to make queenless colonies queenright, and to operate hundreds of skeps.

Readings

iBeehive. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beehive#Skeps

iiKritsky, G. (2017). Beekeeping from antiquity through the middle ages. Annual Review of Entomology 62:249-264. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-031616-035115

iiiLevett, J. (1634). The ordering of bees: or, the history of managing them. From time to time, with their hony and waxe, shewing their nature and breed. As also what trees, plants, and hearbes are good for them, and namely what are hurtfull: together with the extraordinary profit arising from them. Set forth on a dialogue resolving all doubts whatsoever. Thomas Harper, for John Harison. Accessible online through the National Library of Australia at http://gateway.proquest.com/openurl?ctx_ver=Z39.88-2003&res_id=xri:eebo&rft_val_fmt=&rft_id=xri:eebo:image:203420

ivCrane,

E. (1963) in The

archaeology of beekeeping,

Basket

hives used open end down (skeps), pp. 99-111. Gerald Duckworth &

Co. Ltd, The Old Piano Factory, London.

Crane, E. (1999). The

world history of beekeeping and honey hunting.

Routledge, New York,

Chapter 27,

pp. 238-257. Murphy, P. (2018). Galway Beekeepers’ Association

[Cumann Beachairi na Gaillimhe] Skeps.

http://galwaybeekeepers.com/skeps/

vHarley MS 3244 (1236-c 1250). Bestiary. Rubric: ‘Incipit liber de natura bestiarum’, incipit: ‘Leo fortissimus bestiarum’.Decoration: Bees f. 57v. http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=harley_ms_3244_f057v

viUniversity of Aberdeen special collections and museums. The Aberdeen Bestiary – ms 24 (c. 1200). The Aberdeen Bestiary. Creation of the animals Folio 63r – De apibus; Of bees. https://www.abdn.ac.uk/bestiary/ms24/f63r

viiOnly two species of honey bees, Apis mellifera and Apis cerana, from the Apis subgenus Apis have been successfully cultivated. Thomas Seeley argues they have never been truly domesticated.

viiiDams, M. and Dams, L. (1977). Spanish rock art depicting honey gathering during the Mesolithic. Nature 268 (5617): 228–230. doi:10.1038/268228a0 See also Beekeeping. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beekeeping

ixBowen, A.H. (1923). The old straw skep. American Bee Journal 63(3):126-127. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=wu.89043710201;view=1up;seq=686

xMorrison, W.K. (1907). Gravenhorsts system in Germany. The peculiar form of his hive and frame. Gleanings in Bee Culture 35(1):30-31. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.31951d00953180r;view=1up;seq=24

xiDemuth, G.S. (1921). Swarm Control. Farmers Bulletin 1198:1-45. https://ia601401.us.archive.org/32/items/CAT87202908/farmbul1198.pdf

xiiWatch video with Jack Cary an 80 year old Irish beekeeper with Tommy Donovan. Jack has kept bees for seventy years and is steeped in the art of skep making and keeping bees. Hands: of bees & bee skeps https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=99MBkslFhGU&feature=youtu.be

xiiiButler, C. (1609). The feminine monarchie: or a treatise concerning bees, or a hive ordering of them: wherein, the truth found out by experience and diligent observation, discovereth the idle and sound concepts which may have written about this subject. Printed by Joseph Barnes, Oxford. Also titled and reprinted as Butler, C. (1623). The historie of bees. Shewing their admirable nature, and properties, their generation, and colonies, their government, loyaltie, art, industrie, enemies, warres, magnamimitie, &c. together with the right ordering of them from time to time: and the sweet profit arising thereof. Printed by John Haviland for Roger Jackson, Fleetstreet London, 217 pp. Chapter 3, Of the hives, and the dressing of them, pp. 62-79. Book downloadable at https://books.google.com.au/books/about/The_Feminine_Monarchie_Or_the_Historie_o.html?id=f5tbAAAAMAAJ&redir_esc=y

xivSoutherne, E. (1593). Bee Culture: A treatise concerning the right use and ordering of bees: newlie made and set forth according to the authors owne experience: (which by any heretofore hath not been done). Orwin for Thomas Woodcocke, 18 pp. http://find.galegroup.com.rp.nla.gov.au/mome/quickSearch.do?now=1558780323606&inPS=true&prodId=MOME&userGroupName=nla

xvSeeley, T.D. and Morse, R.A. (1976). The nest of the honey bee (Apis mellifera). Insectes Sociaux 23(4):495-512. DOI: 10.1007/BF02223477 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/269996264_The_nest_of_the_honey_bee_Apis_mellifera_L Loftus, J.C., Michael L. Smith, M.J. and Thomas D. Seeley, T.D. (2016). How honey bee colonies survive in the wild: testing the importance of small nests and frequent swarming. PLoS One11(3):e0150362 Published online 2016 Mar 11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150362 Seeley, T.D. (2017). Life-history traits of wild honey bee colonies living in forests around Ithaca, NY, USA. Apidologie48: 743-754. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-017-0519-1

xviTusser, T. (1557a). A Hundreth Good Pointes of Husbandrie http://www.archive.org/stream/fivehundredpoint08tussuoft/fivehundredpoint08tussuoft_djvu.txt

xviiTusser, T. (1557b). A Hundreth Good Pointes of Husbandrie http://www.luminarium.org/renascence-editions/tusser1.html

xviiiRichardson, H. D. (1849). The Hive and the Honey-bee: with plain directions for obtaining a considerable annual income from this branch of rural economy. J. McGlashan, p.58. https://ia800200.us.archive.org/26/items/hivehoneybeewith00rich/hivehoneybeewith00rich.pdf

xvixDespite claims to the contrary, the open mating nature of honey bee queens has not led to any significant decline in their gene pool, rather it is now more mixed and regional subspecies are not the pure strains they once were.

xxWinston, M.L. (2014). Bee time: Lessons from the hive, Chapter 3, Killer Bees, pp. 40-56. Harvard University Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England.

xxiGalle, H.-K. (Ed): Fuchs, P. and Nemes, Z. (Co-Eds) E2962. IWF 9 (1986). Skep beekeeping: Work during the cast swarm period/Summer work during the heather bloom (1979 and 1983). [Mitteleuropa Nördliches Niedersachsen – Arbeiten zue Zeit der Nachschwärme in einer Korgimkerei] Encyclopaedia Cinematographer iwf.de https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ns2HMtFJRaE

Be the first to comment