Alan Wade and Dannielle Harden

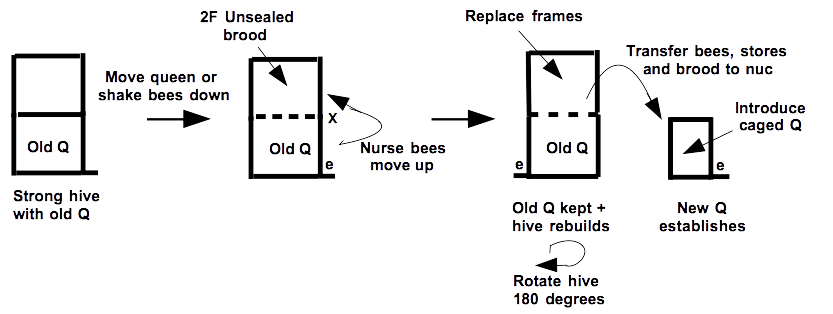

Last month we discussed a couple of simple ways to get caged mailed queens safely into hives. We looked at some nifty tricks (Figure 1) to avoid having to find the old queen, that is just when the postie delivered your caged queen.

We now turn to the slightly more challenging task of raising a few queens and employing the raised cells to requeen hives.

Since visiting the topic of requeening in the last newsletter https://actbeekeepers.asn.au/bee-buzz-box-september-2019 [Yes it does have a ‘false’ September label that that’ s OK.] we’ve come across a hive in the early stages of requeening itself. The jargon term for this common process of self-queening is called supersedure. All that means is that the colony is replacing its queen without swarming.

Had we simply left the colony to its own devices, a new unmarked queen would have ‘magically’ appeared. Apart from then marking her a distinctive ‘ring-in’ colour, and checking that she was laying well, every detail of the job of requeening would have been done by the bees themselves.

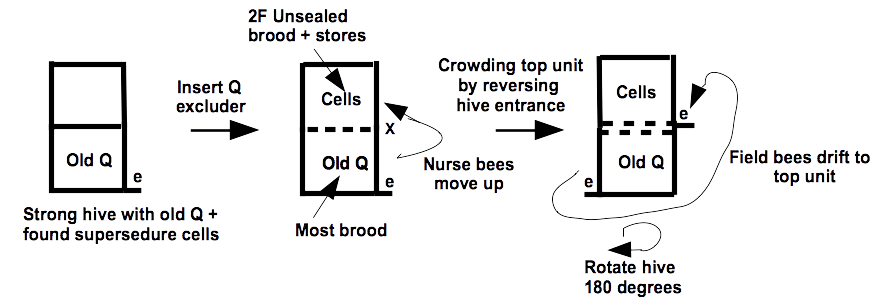

On this occasion, however, we decided to intervene gently. We did this purely to make quite sure the just started queen cells got the very best attention. We fed them liberally with 2:1 sugar water and artificially strengthened them – by inserting a double screen and changing hive entrance locations – so that the bees would return to the unit with started supersedure cells – and fully focus on queen cell building.

Here, as you can see, we have employed the mother colony as the cell builder using the aforementioned double screen. The colony has been reorganised to capture returning forager bees, maximising the nutrition of attendant nurse bees (Figure 2) .

Commercial queen breeders adopt the same strategy but start the process by grafting day-old larvae into plastic queen cell cups. They then transfer racks of thirty or more of these started queen cells into strong queen-right builder colonies above queen excluders.

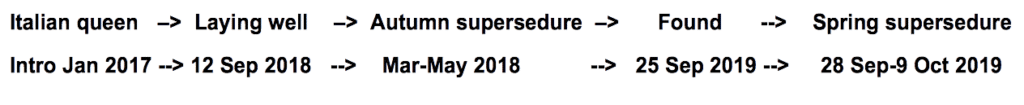

When we checked the lineage records of the queen, we found that our newly developing gynes (potential queens) had by now out-crossed a couple of times.

Since the old queen was failing anyway we thought it best to allow the bees to select a queen cell and mate independently of the old queen below. Around the end of October, once we’ve checked the new queen is OK, we will remove the failing queen below and simply take out the double screen. Keeping two queens for a stint more or less guarantees that requeening will be successful and that the colony won’t be set back.

A more deliberate effort to raise queens

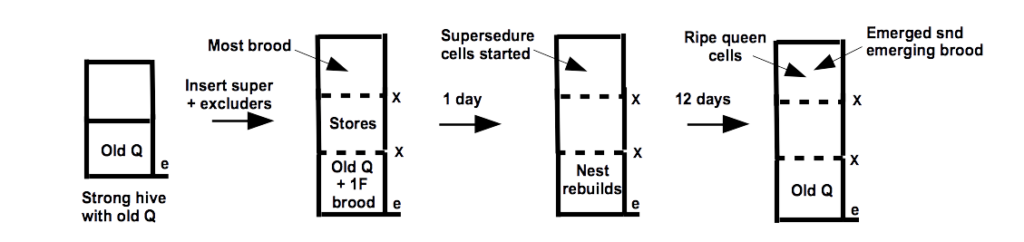

Encouraged by the finding of a colony taking on the task of requeening itself, the 28 September ‘Colony Building and Swarm Prevention Class’ set out to try the old swarm control trick of separating the queen from her brood in another strong colony. Under good conditions, such as those prevailing at the time, you get much more than you bargained for. A strong colony sets to and raises less than a handful of high quality supersedure queen cells (Figure 3).

[Demaree swarm control in colony J05]

On careful inspection of this image you will notice that the cell shown is attached to the surface of the comb and has been built from scratch. Emergency queens, raised from colonies made queenless and built in a hurry, originate from a modified worker cell larvae buried deep in the worker cells matrix.

Left entirely to its own devices this strong colony headed by its old queen would almost certainly have swarmed. In this instance we achieved the double whammy, achieving swarm control and obtaining a few new queens raised from a high calibre queen, that is employing a queen that had already performed well over two seasons.

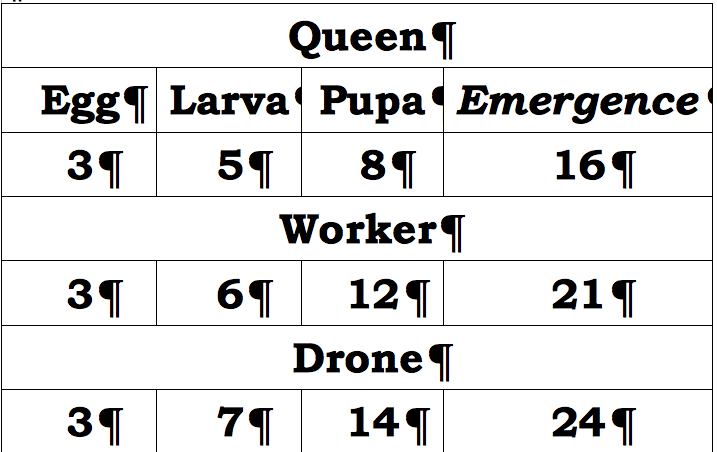

It’s nice to have some control over the calibre of our queens, if not the free-ranging drones of Jerrabomberra that will mate with them. The handy table below has helped us plan both colony buildup and our mini-requeening program: add in a month for drones to mature and about ten days for a new queen to mate and start laying.

Source: Oldroyd and Wongsiri (2016)

One lesson we learnt was that supersedure cells are produced progressively not as a single, if small, all-at-once batch. This staged queen raising increases the chance of successful queen replacement if a daughter queen either fails to mate or to return to the parent hive.

Left to their own devices, however, only one of the raised queens ever survives the inter-queen (technically gyne) rivalry. We simply got in and harvested the cells before this fatal battle occurred. This scenario is reminiscent of the feud between Cain, the keeper of sheep, and his brother Able of Old Testament and Q’ran fame. Cain slew Able so we are the sons and daughters of Cain, not Able (see Readings).

At time of going to print three out four colonies had established supersedure queens though two had not commenced laying. One colony became queenless.

Lessons learnt

We hope we have demonstrated that a few new queens might be raised successfully in your backyard.

We’ve also learnt that, while supersedure results in seamless queen replacement, raising of such queens is progressive. Not all queens are started at once so queen mating of harvested cells is staged. Queens may emerge over a period or a week or more, not on the same day as occurs where queens are mass produced.

A case for requeening

This brings us round to the eternal topic of requeening hives, whether to do so or not. There are many advocates of never requeening your hive, though we are not of that persuasion.

Natural beekeeping has its place, that is amongst people who own bees for their own keeps’ sake. However we are of the view that a mixture of nuisance and colony-debilitating swarming, a greater susceptibility to disease – if colonies are weak – and an expectation of a poor honey crop is the more likely outcome.

This said, there are few hard and fast rules to beekeeping, though a colony without a queen, one with a queen on her last legs or one with a queen heading a heavily diseased colony is destined for the dustbin.

In our experience practicing beekeeping by regular requeening with productive stock of gentle disposition and with a modicum of disease resistance, combined with good hive nutrition, makes beekeeping a whole lot more productive and less problem prone.

Join us for future requeening events, that is if you want to check out seamless matriarchal succession, one designed pep up colonies blighted by failing or clapped out queens.

Readings

Old Testament and Qur’an readers will be well acquainted with the story of Adam and Eve and their errant offspring. See Genesis 4:8-9 https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Genesis+4%3A8-9&version=KJV and the Qur’an 5:27-32. https://quran.com/5/27-32

Oldroyd, B.P. and Wongsiri, S. (2006). Asian honey bees: Biology, conservation and human interactions. Harvard University Press. http://trove.nla.gov.au/version/45924294 Australian National Library Dewey Number N 595.799 044

Be the first to comment