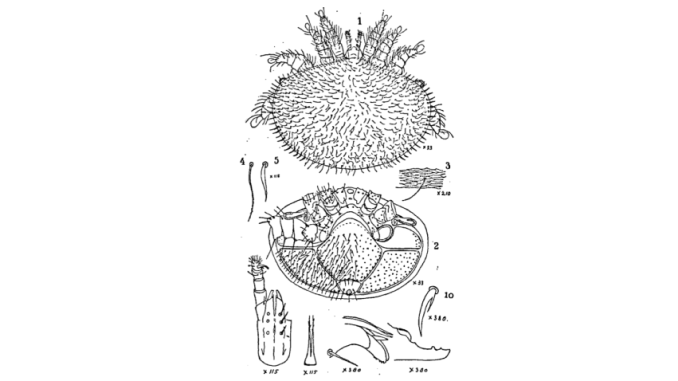

First ever drawing of a honey bee mite, Varroa jacobsoni from Semarang in Java.

Source: Oudemans (1904b)

Alan Wade

Parasites, in a phrase, are predators that eat prey in units of less than one. Tolerable parasites are those that have evolved to ensure their own survival and reproduction but at the same time with minimum pain and cost to the host.

Edward O. Wilson (2014)

One hundred and twenty years ago highly revered Dutch zoologist and mite taxonomist Anthonie Cornelis Oudemans (1904b) proclaimed:

The Museum above mentioned [Zoological Museum at Leyden] received these mites (four females) and the bees, from Mr. Edward Jacobson at Semarang [Java]…

At all events the discovery of these female mites is a fortunate one and a brilliant contribution to parasitism.

This is an understatement. The parasite Oudemans so described (Frontispiece) was none other than the genus type species Varroa jacobsoni, later split off from the now widespread mainland Asian species Varroa destructor: Together the two varroa species, both parasites of their native honey bee host Apis cerana, are emphatically not natural predators of the honey bees we keep. Indeed both mites did not parasitise Apis mellifera until the mid 20th Century. As a footnote, Varroa destructor was not recognised as separate from the Varroa jacobsoni taxon, that was not until the pioneering study of Anderson and Trueman (2000).

The first and only parasitic mite of the western honey bee known to science – and beekeepers – was not discovered until 1921. The role of this parasite, the tracheal mite, as the ‘cause of Isle of White disease’ led to one of the great disputes of bee disease science. The aetiological role Acarapis woodi (the tracheal mite) as a parasite was sadly and badly overstated.

The tracheal mite enigma

You may not have read John Rennie’s account of the parasitic mite Tarsonemus woodi (Acarapis woodi) associated with western honey bees. Published as a lengthy memoir by the North of Scotland College of Agriculture (Rennie, 1923), it was anticipated by an earlier note published in Bee World as ‘Short Notes on Acarine Disease’ (Rennie, 1921a) and by a taxonomic dissertation in the Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (Rennie 1921b). The published 1923 narrative tells us much of what we might want to know about tracheal mite biology and its beekeeping import. As Bailey (1961) later recounted:

The mite Acarapis woodi (Rennie) is often assumed to be highly pathogenic for its host, the honeybee, but recent field and laboratory experiments have shown that, although individual bees have their lives shortened by infestation, the effect is very slight and may always have been so. Disease was not usually visible in summer, even in very heavily infested colonies, but the mortality of colonies in winter was correlated with their infestation (Bailey, 1958; Bailey and Lee, 1959).

So we might assume that early and foreboding notes in the austere journal Nature – and popular press – attributing mass colony mortality to the tracheal mite Acarapis woodi (Anon, 1912, 1916, 1917; Ellis, 1918) were in error. We must conclude that this mite is hosted naturally by Apis mellifera and that the parasite and host had long learnt to live with one other. There were other, if not well defined, causes of the wholesale 1910s losses of colonies in the United Kingdom and in Europe later in the 1920s.

To digress and nearer to home we again recall Uncle Harry’s uncanny, if mistaken, observations of wild bush creatures and the maladies that befall them (Figure 1):

‘It was just after a big flood and all the gilguys were full. Plenty of fish in them too. I threw a few lines in one day and had just sat down when I heard a frog croaking just near me. I looks around and here’s a big carpet snake with the frog in his mouth.

‘I decided to try and get that frog for a cod bait. Had a flask of rum in me pocket, so I poured a drop into the crown of me hat and puts it in front of the snake. Sure enough he dropped the frog at my feet, then looks at me in a real appealing sort of way. I poured him a big dose this time and he downed it straight away. It made him cough a bit, then he staggers up to a wilga and collapses in the shade. He was as drunk as a brewer’s donkey.

‘There was no shortage of bait after that. Day after day he brought frogs to pay for his rum. I had a big supply in the hut, and after the first month he got lazy and just hung about bludging. I decided to do something about it.

Figure 1 The proof is in the pudding.

Keith Garvey (1981)

All good things must come to an end so Uncle Harry got his snake thoroughly drunk and packed him off to Taronga Zoo:

Uncle Harry paused to light his pipe. He took a long pull of smoke, and the noise was like a toilet regurgitating when the chain is pulled.

‘And you never heard of the snake again’ I prompted.

Uncle Harry’s leathery countenance assumed a sad expression. ‘Yes,’ he said mournfully. ‘The zoo wrote to me and told me he died on arrival. Too long without a drink in that box, and the DTs killed him. He was doomed anyway, as the post-mortem showed. He was in bad physical shape with silicosis of the liver.’

‘You mean cirrhosis of the liver’ I corrected.

‘That’s what I said, ‘chrissos of the liver’ replied Uncle Harry. ‘I’m well read on diseases, even if I didn’t study medicine. Anyhow, boy, it proved to me that rum is a dangerous drink for those that can’t handle it. There’s still a couple of nips there in the bottle, we better finish her off.’

Invertebrates in general are host to a range of Acarapis species. Of these only A. woodi, A. dorsata and A. externus are associated with honey bees. Another putative species Acarapis vagans (Schneider, 1941; Delfinado-Baker and Baker, 1982; Sapcaliu et al., 2015) has since been shown to be synonymous with Acarapis woodi so there remain just three bothersome and rather similar parasites. You may not realise it but both A. dorsata and A. externus are known in Australia, but neither are common nor known to inflict significant damage.

I have long taken the view that A. woodi is relatively harmless, noting that Denmark et al. (2004), Carreck and Neuman (2010), and Johnston (2023) are similarly dismissive of the mite causing much damage mainly based on the findings of Dr Leslie Bailey [1922-2017] (1958, 1959, 1961, 1963, 1964a, 1964b).

I recently encountered informed views that we should not be so complacent about the potential impact of the tracheal mite though it’s also hard to argue against such sober opinions. Brother Adam (1968) was certainly not of the now consensus view. He carefully referenced several reports (Cooper, 1905, 1906; Editorial, Notices, &c. 1906a, 1906b, 1907; Silver, 1907) that indicated that factors such as weather could not be attributed to wholesale bee losses, the Swiss Bee Research Unit (Sammataro 2006; Sammataro et al., 2023), in conjunction with the USDA, reflecting a similar view. I have no informed opinion beyond suggesting that the tracheal mite, appears to be causing mortality in Apis cerana japonica in Japan (Kojima et al., 2011). As a parasite A. woodi does take some toll on honey bees so we should be vigilant in ensuring this mite is not brought into Australia or New Zealand. It is certainly now very widespread, for example seemingly rampant in Mexico (Lozano et al., 1989).

Concerning mites

Though Varroa is in the spotlight we might hope that our bees will not someday be put at further risk from other predacious mites. In surveying the spectrum of honey bee phoretics that may come our way we may conclude that only Euvarroa (mite bee parasites of the dwarf honey bees) and Acarapis will not bring our bees down. So what might these other mites be?

The world of mites and microbes are forever a mystery to all but those who spend their lives peering down the eponymous microscope, an instrument that satirist Hilaire Belloc was wont to purloin (Figure 2):

Figure 2 The microbe

Hilaire Belloc

On each of which a pattern stands,

Composed of forty separate bands

His eyebrows of a tender green

All these have never yet been seen—

But Scientists, who ought to know,

Assure us that they must be so—

Oh! let us never, never doubt

What nobody is sure about.

The Microbe

Hilaire Belloc

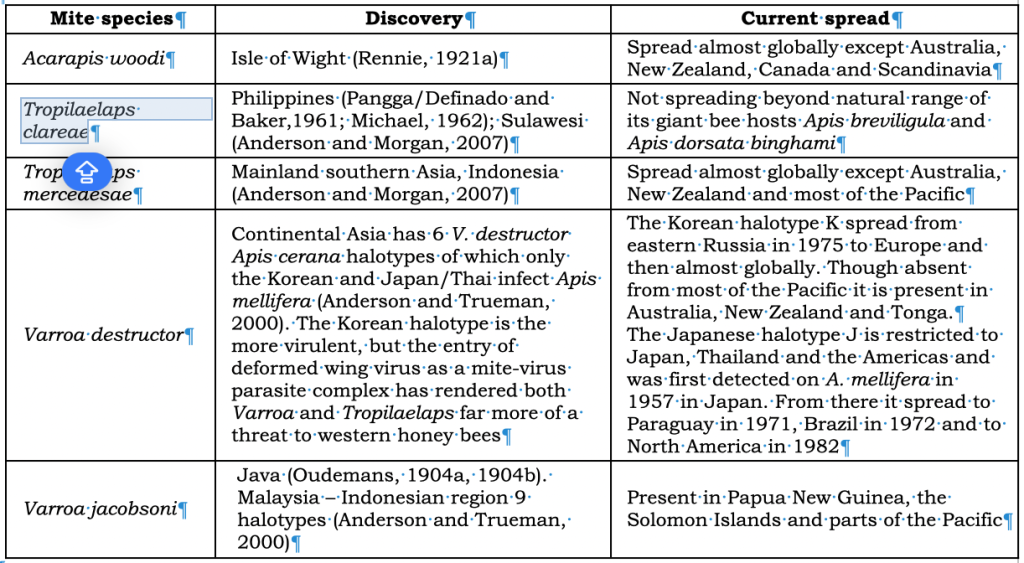

Table 1 lists the parasitic mites we know to be of concern. Of considerable interest will be the eventual fallout of the present Australian invasion of Varroa destructor and the potential import of Varroa jacobsoni (now present widely in the Pacific) and Tropilaelaps mercedesae (present in Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and Fiji).

Table 1 Discovery and spread of destructive honey bee mites.

* The various routes of spread of the two Varroa halotypes on Apis mellifera are detailed by Solignac et al. (2005). Navajas et al. (2010) map the K and J halotypes including variants and indicate that there are additional halotypes infecting Apis mellifera that are yet to move out of Asia.

Studies by the CSIRO (Roberts and coworkers, 2019, 2020a, 2020b) showed that while these two mites initially caused major damage to beekeeper enterprises in Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands that bees have now adapted in the absence of deformed wing virus and are operating without treatment. We now know much about measures to control Varroa, while others such as Woyke (1987) have begun the long process of finding ways to control Tropilaelaps (Pettis, et al., 2017). What may happen in Australia, also in the present absence of deformed wing virus, is conjectural though Roberts et al. (2020b) note:

We conclude from these findings that A. mellifera in PNG may tolerate V. jacobsoni because the damage from parasitism is significantly reduced without DWV. This study also provides further evidence that DWV does not exist as a covert infection in all honey bee populations, and remaining free of this serious viral pathogen can have important implications for bee health outcomes in the face of Varroa.

Will Acarapis, Varroa, Tropilaelaps or a new species of Nosema (Chemurot et al., 2017) come to bother our bees? It seems fairly certain that Euvarroa and the south American parasite of Apis mellifera scutellata, Leptus ariel, are of little concern but others – two species each of Varroa and Tropilaelaps – may well plague our bees and that Varroa destructor is spreading in Australia and doing so now.

But from a honey bee perspective the problem with mites is not new. Ben Oldroyd and Siriwat Wongsiri (2006) tell us that the mites troubling our honey bees came from a suite of Asian honey have been in a long battle with their native hosts: these are of course the longstanding parasites of the Apis cerana, Apis dorsata and Apis florea clades. Now and then pockets of these bees get stressed and they, too, like the unloved street dog, fall victim to their free-loading parasites.

In a ‘real appealing sort of way’, let’s hope our bees can learn to live with Varroa and urge our quarantine guardians to keep out lurking fates worse than (or as bad as) Varroa destructor, not least the honey bee deformed wing virus, the insidious Tropilaelaps mites, Varroa jacobsoni and sundry other pests such as Asian hornets.

In the likely event that our bees will end up with several parasitic mites, one really hopes that our bees learn to adapt and that ‘the suckers’ end up in units of less than one. In such a very optimistic scenario our bees might be operated, well provisioned, treatment free. More likely the parasites will present themselves in E.O. Wilson’s terminology of ‘units greater than one’ and we, together with our bees, will be in for a battle royale.

Readings

Anon (20 June 1912). The Isle of Wight bee disease. Nature 89:410. https://doi.org/10.1038/089410a0

Anon (20 April 1916).F. Isle of Wight disease in bees. Nature 97:161. https://www.nature.com/articles/097161a0#citeas

Anon (23 August 1917).The Isle of Wight bee disease. Nature 99:507-508. https://doi.org/10.1038/099507a0

Adam, Brother. (1968). Isle of Wight or acarine disease: Its historical and practical aspects. Bee World 49(1):6-18. http://www.pedigreeapis.org/biblio/artcl/BAacarine68en.pdf

Anderson, D.L. and Morgan, M.J. (2007). Genetic and morphological variation of bee-parasitic Tropilaelaps mites (Acari: Laelapidae): New and re-defined species. Experimental and Applied Acarology 43(1):1-24. https://doi:10.1007/s10493-007-9103-0

Anderson, D.L. and Trueman, J.W.H. (2000). Varroa jacobsoni (Acari: Varroidae) is more than one species. Experimental and Applied Acarology 24:165-189. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Denis-Anderson/publication/283318630_Anderson_and_Trueman_2000/links/5632c7c908ae242468da00af/Anderson-and-Trueman-2000.pdf

Bailey, L. (1958). The epidemiology of the infestation of the honey bee, Apis mellifera L., by the mites Acarapis woodi (Rennie), and the mortality of infested bees. ParasitoIogy 48(3-4):493-506. https://www.wellesu.com/10.1017/s0031182000021430

Bailey, L. and Lee, D.C. (1959). The effect of infestation with Acarapis woodi (Rennie) on the mortality of honey bees. Journal of Insect Pathology 1(1):15-24. Cited by Bailey (1961).

Bailey, L. (1961). The natural incidence of Acarapis woodi (Rennie) and the winter mortality of honeybee colonies. Bee World 42(4):96-100. https://doi:10.1080/0005772x.1961.11096851

Bailey, L. (May 1963). ‘The Isle of Wight Disease: The origin and significance of the myth’ presented to the Central Association of Bee-Keepers, 8 Gloucester Gardens, Ilford, Essex, 10pp. http://www.dave-cushman.net/bee/baileyiow.pdf

Bailey, L. (1964a). The Isle of Wight disease: The origin and significance of the myth. Bee World 45(1):32-37. https://doi:10.1080/0005772X.1964.11097032 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0005772X.1964.11097032

Bailey, L. (1964b). The Isle of Wight disease: The origin and significance of the myth. Bee World 42(4):96-100. https://repository.rothamsted.ac.uk/item/8w51y/

Bailey, L. (2002). The Isle of Wight disease. Central Association of Bee-Keepers, Poole, UK. 11pp. https://www.nature.com/articles/089410a0 abstract only

Bailey, L. and Ball, B.V. (1991). Honey bee pathology (2nd Edition), Chapter 7, Parasitic mites pp.78-93. Academic Press, London, UK. 193pp. https://sci-hub.sidesgame.com/10.1016/b978-0-12-073481-8.50011-4

Burgett, M., Akratanakul, P. and Morse, R.A. (1983). Tropilaelaps clareae: A parasite of honeybees in South-East Asia. Bee World 64(1):25-28. https://doi:10.1080/0005772X.1983.11097904 https://www.wellesu.com/10.1080/0005772X.1983.11097904

Carreck, N. and Neumann, P. (2010). Honey bee colony losses. Journal of Apicultural Research 49(1):1-6. https://doi:10.3896/IBRA.1.49.1.01

Chemurot, M., De Smet, L., Brunain, M., De Rycke, R. and de Graaf, D.C. (2017). Nosema neumanni n. sp.(Microsporidia, Nosematidae), a new microsporidian parasite of honeybees, Apis mellifera in Uganda. European Journal of Protistology 61(Part A):13-19. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0932473917301001

Cooper, J.M. (per Eds) (1905). Homes of the honey bee: The apiaries of our readers. British Bee Journal and Bee-Keepers’ Adviser 33(801):175-176. https://ia601307.us.archive.org/23/items/britishbeejourna1905lond/britishbeejourna1905lond.pdf

Cooper, H.M. (1906). Bee paralysis: Is its cause known? [6200.] British Bee Journal and Bee-Keepers’ Adviser 34(1233):56-57. https://dn790000.ca.archive.org/0/items/britishbeejourna1906lond/britishbeejourna1906lond.pdf

Delfinado, M.D. and Baker, E.W. (1961). Tropilaelaps, a new genus of mite from the Philippines (Laelapidae [s. lat.], Acarina). Fieldiana Zoology 44(7):53-56. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/partpdf/36189

Delfinado, M.D. (1963). Mites of the honeybee in South-east Asia. Journal of Apicultural Research 2(2):113-114. https://www.wellesu.com/10.1080/00218839.1963.11100070

Delfinado-Baker, M. and Baker, E.W. (1982). Notes on honey bee mites of the genus Acarapis Hirst (Acari: Tarsonemidae). International Journal of Acarology 8(4):211-226. https://doi:10.1080/01647958208683299

Denmark, H.A., Cromroy, H.L. and Stanford, M.T. (2004). Honey bee tracheal mite, Acarapis woodi (Rennie) (Arachnida: Acarina: Tarsonemidae): EENY-172/IN329, 11/2000. EDIS, 2004(2). https://agrilife.org/masterbeekeeper/files/2015/04/Honey-Bee-Tracheal-Mite.pdf

Editorial, Notices, &c. (1906a). The latest bee scare. British Bee Journal and Bee-Keepers’ Adviser 34(1256):281. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/83073#page/291/mode/1up

Editorial, Notices, &c. (1906b). The latest bee scare: Bee-paralysis. British Bee Journal and Bee-Keepers’ Adviser 34(1260):321-323. https://dn790000.ca.archive.org/0/items/britishbeejourna1906lond/britishbeejourna1906lond.pdf

Editorial, Notices, &c. (1907). The bee-epidemic in The Isle of Wight. British Bee Journal and Bee-Keepers’ Adviser 34(1260):321-323. https://ia601301.us.archive.org/35/items/britishbeejourna1907lond/britishbeejourna1907lond.pdf

Ellis, D. (1918). Bee Disease. Nature 101:103-104. https://www.nature.com/articles/101103c0

Garvey, K. (1981). The alcoholic snake. In Tales of my Uncle Harry. ABC Books, Sydney.

Kojima, Y., Toki, T., Morimoto, T., Yoshiyama, M., Kimura, K. and Kadowaki, T. (2011). Infestation of Japanese native honey bees by tracheal mite and virus from non-native European honey bees in Japan. Microbial Ecology 62(4):895-906. https://doi:10.1007/s00248-011-9947-z

Laigo, F.M. and Morse, R.A. (1968). The mite Tropilaelaps clareae in Apis dorsata colonies in the Philippines. Bee World 49(3):16-118. https://doi.org/10.1080/0005772X.1968.11097211 https://www.wellesu.com/10.1080/0005772X.1968.11097211

Lozano, L.G., Moffett, J.O., Campos P, B., Guillen M, M., Perez E, O.N., Maki, D.L. and Wilson, W.T. (1989). Tracheal mite Acarapis woodi (Rennie) (Acari: Tarsonemidae) infestations in the honey bee, Apis mellifera L. (Hymenoptera: Apidae) in Tamaulipas, Mexico. Journal of Entomological Science 24(1):40-46. https://jes.kglmeridian.com/view/journals/ents/24/1/article-p40.xml

Michael, A.S. (1962). Tropilaelaps clareae, a mite infesting honeybee colonies. Bee World 43(3):81-82. Cited by Burgett, M., Akratanakul, P. and Morse, R.A. (1983). Tropilaelaps clareae: A parasite of honeybees in South-East Asia. Bee World 64(1):25–28. https://doi:10.1080/0005772X.1983.11097904

Navajas, M., Anderson, D.L., de Guzman, L.I., Huang, Z.Y., Clement, J., Zhou, T. and Le Conte, Y. (2010). New Asian types of Varroa destructor: A potential new threat for world apiculture. Apidologie 41(2):181-193. https://www.apidologie.org/articles/apido/pdf/2010/02/m09007.pdf

Oldroyd, B.P. and Wongsiri, S. (2006). Asian honey bees: Biology, conservation and human interactions. Harvard University Press.

Oudemans, A.C. (1904a). Nog iets aangaande de Afbeeldingen met beschrijving van insecten, schadelijk voor naaldhout. Entomologische Berichten 18:156–164. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/8982540#page/191/mode/1up

Oudemans, A.C. (1904b). On new genus and species of parasitic acari. Note VIII Varroa nov. gen: Notes from the London Museum 24:216-222. https://ia802907.us.archive.org/14/items/notes-from-leyden-museum-24-216-222/notes-from-leyden-museum-24-216-222.pdf https://archive.org/details/notes-from-leyden-museum-24-216-222

Pettis, J.S., Rose, R. and Chaimanee, V. (2017). Chemical and cultural control of Tropilaelaps mercedesae mites in honeybee (Apis mellifera) colonies in Northern Thailand. PloS ONE 12(11):p.e0188063. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0188063&type=printable

Rennie, J. (1921a). (4) Isle of Wight Disease in hive bees—Acarine disease: The organism associated with the disease — Tarsonemus woodi, n. sp.. Chapter 29 Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 52(4):768-779. https://doi:10.1017/s0080456800016008 https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/116596#page/5/mode/1up

Rennie, J. (1921b). Notes on acarine disease.–V. Bee World 3(4):95-96. https://sci-hub.sidesgame.com/10.1080/0005772x.1921.11095153 https://doi:10.1080/0005772x.1921.11095153

Rennie, J. (1923). Acarine disease explained. North of Scotland College of Agriculture, Memoir No.6, 50pp. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924003709619&seq=5

Roberts, J.M., Schouten, C.N., Sengere, R.W., Jave, J. and Lloyd, D. (2019). Different strategies to manage Varroa jacobsoni and Tropilaelaps mercedesae in Papua New Guinea. BioRxiv 2019-12. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/biorxiv/early/2019/12/19/2019.12.17.880393.full.pdf

Roberts, J.M.K., Schouten, C.N., Sengere, R.W., Jave, J. and Lloyd, D. (2020a). Effectiveness of control strategies for Varroa jacobsoni and Tropilaelaps mercedesae in Papua New Guinea. Experimental and Applied Acarology 80(3):399-407. https://doi:10.1007/s10493-020-00473-7

Roberts, J.M., Simbiken, N., Dale, C., Armstrong, J. and Anderson, D.L. (2020b). Tolerance of honey bees to Varroa mite in the absence of deformed wing virus. Viruses 12(5):575. https://sci-hub.sidesgame.com/10.3390/v12050575

Sammataro, D. (2006). An easy dissection technique for finding the tracheal mite, Acarapis woodi (Rennie) (Acari: Tarsonemidae), in honey bees, with video link. International Journal of Acarology 32(4):339-343. https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/31186/Sammataro-VP(32-4)-November%204.pdf

Sammataro, D., Hayden, C., de Guzman, L., George, S. and Ochoa, R. (accessed 21 May 2025). Tracheal mites: Tracheal mite, Acarapis woodi (Rennie) (Acari: Tarsonemidae). In Beebook, Swiss Bee Research Centre, Federal Department of Economic Affairs, Research Station, Agroscope Liebefeld-Posieux ALP, Bern, Switzerland. https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/60500500/PDFFiles/501-600/503-Sammataro–Tracheal%20Mite%20Chapter.pdf

Sapcaliu, A., Savu, V., Mateescu, C. and Rădoi, I. (2015). Case study on a possible external mite infestation (A. externusor A. dorsalisor A. vagans) at drone brood of Apis mellifera carpathica bees in a(n) apiary from southern Romania. Agriculture and Agricultural Science Procedia 6:82-386. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S221078431500234X

Schneider, H. (1941). Untersuchungen über die Acarapis-Milben der Honigbiene. Die Flügel- und Hinterleibsmilbe. Vorläufige Mitteilung. Mitteilungen der Schweizerischen Entomologischen Gesellschaft 18(6):318-327. https://ira.agroscope.ch/fr-CH/publication/16050

Sevilla, V.J. (1963). Observations on the life history and habits of three new acarine pests of honeybees in the Philippines. University of the Phillipines, BSc thesis, 42pp. Tropilaelaps clareae Delfinado & Baker, Varroa jacobsoni Oudm. and Aceosejus sp. Cited by Laigo and Morse (1968) loc. cit.

Silver, J. (1907). The Isle of Wight Bee-Disease. [6731.] British Bee Journal and Bee-Keepers’ Adviser 34(1260):223-224. https://ia601301.us.archive.org/35/items/britishbeejourna1907lond/britishbeejourna1907lond.pdf

Solignac, M., Cornuet, J.M., Vautrin, D., Le Conte, Y., Anderson, D., Evans, J., Cros-Arteil, S. and Navajas, M. (2005). The invasive Korea and Japan types of Varroa destructor, ectoparasitic mites of these Western honeybee (Apis mellifera), are two partly isolated clones. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 272(1561):411-419. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1634981/

Wilson, E.O. (2014). The meaning of human existence. W.W. Norton & Company. p.112.

Woyke, J. (1987). Length of stay of the parasitic mite Tropilaelaps clareae outside sealed honeybee brood cells as a basis for its effective control. Journal of Apicultural Research 26(2):104-109. https://www.wellesu.com/10.1080/00218839.1987.11100745