Alan Wade

Can colonies with two queens fend off Varroa better than single-queen colonies? Or because of the size of their broodnests will two-queeners be more vulnerable to mite infestation?

These are important questions since there is preliminary evidence to suggest that stronger colonies with Varroa are, well managed, less mite prone and hence healthier and more productive.

To address such uncertainty we need to know what colonies headed by an extra queen actually comprise. Only then can we turn to how such colonies with Varroa will perform.

Part A Hives with Two Queens

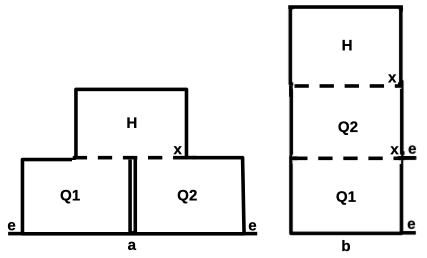

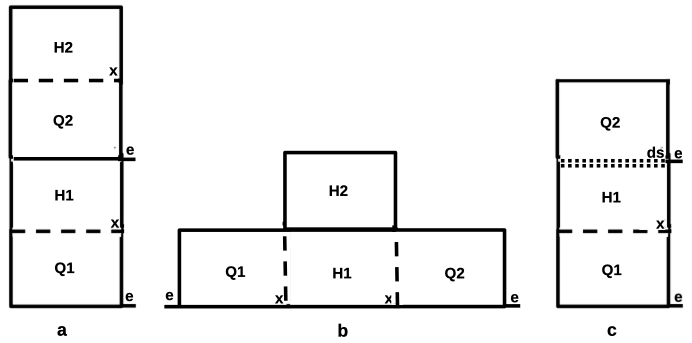

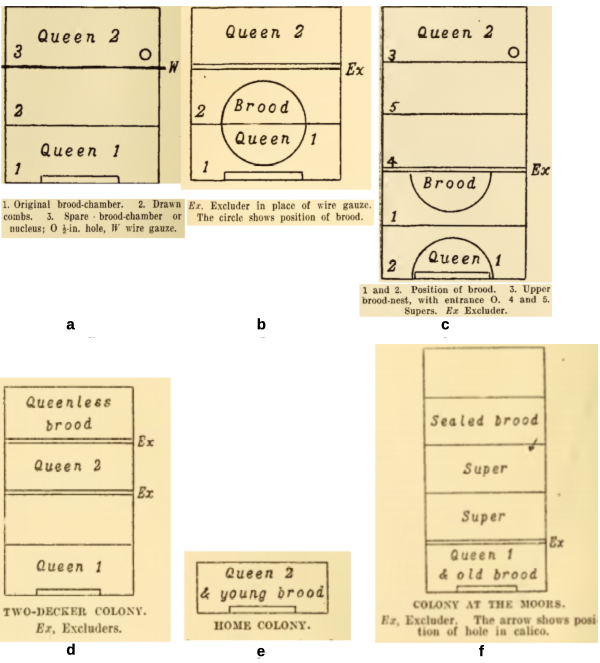

There are two types of colonies that run with an extra queen – or less commonly with additional queens. There are those that operate just as single-queen colonies do but where two or more hives simply share honey supers (Figure 1a). Then there are those hives with more than one queen in the same colony (Figure 1b) shown here with the broodnests nests juxtaposed.

In all setups the queens are kept apart by one or more excluders. Since honey bee colonies with two queens produce a whole lot more honey than equivalent pairs of single-queen hives, the question becomes one of how will colonies with that extra queen loaded with Varroa perform?

Figure 1 Two distinctive hive types with an extra queen: Q = queen; H = honey; x = excluder; e = entrance:

(a) doubled hive with common super storage; and

(b) two-queen hive with shared brood raising and common super storage.

In a forward to an account of running hives with two queens, Medicus (1910) made a clear distinction between what constituted a doubled hive and what a two-queen hive actually was:

…there has nearly always been misunderstanding as to what is meant by a two-queen system, owing to its confusion with the system advocated by the late Mr George Wells… Mr Wells did not advocate working a colony with two (or more) queens, but advocated giving to two stocks a super, or supers, to which both colonies had access. [They] profited by the mutual warmth which two colonies in such close proximity must derive from each other, and this enabled them to build up more rapidly in the spring. This advantage was increased during the honey-flow, when, by having a super common to the two colonies, a larger proportion of nectar-gatherers were able to be liberated from home duties.

…A true double [two-queen] or multiple queen system is one in which a single colony with a single entrance has two or more queens laying at the same time, and the workers of which have access to every part of the hive. The queens may be either loose in a common brood chamber, or kept apart from each other by queen excluders.

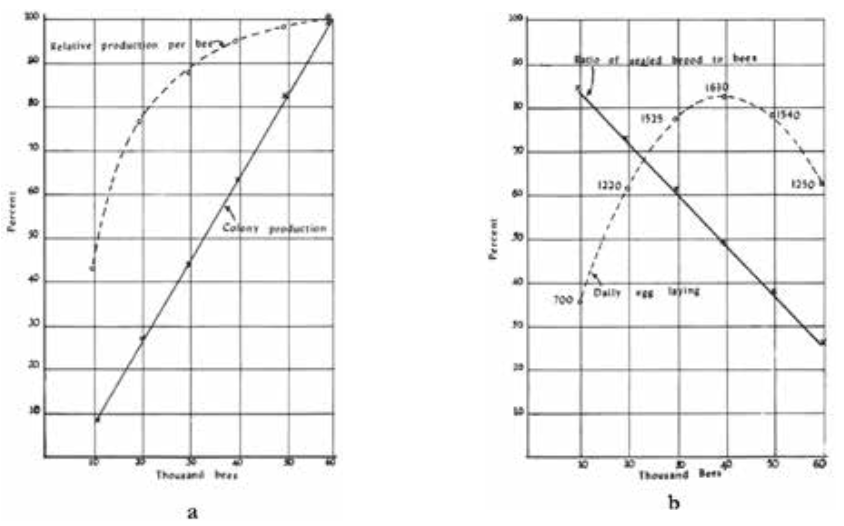

That colonies with that extra queen are disproportionately productive comes down to two queens laying in tandem. They produce almost double the number of bees found in a standard single-queen hive. Clayton Farrar (1968a, 1968b) also showed that as the population grows the average worker bee becomes far more efficient. Fewer bees are needed to raise brood, more bees are freed up to forage and scouts more quickly locate sources of nectar, pollen, propolis and water (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Farrar’s plots of colony performance relative to colony size:

(a) colony production in relation to colony strength and increased productivity per bee grows as the population increases; and

(b) increasing ratio of total bee numbers to amount of brood (expressed as ratio of decreasing brood to adult bees) grows as the population expands freeing up bees to become foragers.

So can outsized colonies, those powered by an extra laying queen, be employed to better outcompete Varroa and overcome the losses in colony productivity attributable to parasitism? Two case studies reflect this surprising supposition?

A doubled hive exemplar from Türkiye

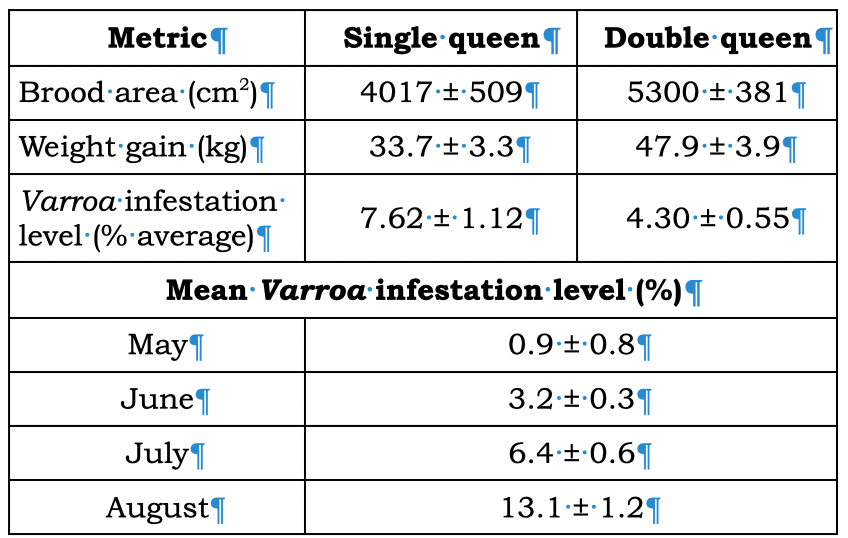

Cengiz, Genç and Cengiz (2019) established forty six single and forty six doubled hives colonies equalising them with a similar number of starting bees and low numbers of Varroa mites. These researchers recorded differences in brood area, weight gain and level of mite infestation as their study progressed (Table 1) concluding that the doubled hive setup:

…had a positive effect on both lowering the Varroa infestation levels and significantly increasing the number of bees found on the honeycomb, the brood area, and the weight gain of the hive in the nectar flow period, resulting in higher honey yields per colony.

Table 1 Relative performance of single queen and doubled hives. Note that the Varroa infestation levels were reported back to front, the level in single-queen hives being roughly twice that found in doubled hives.

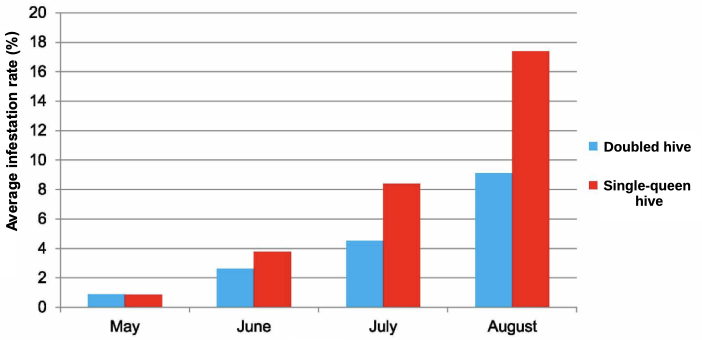

The relative levels of Varroa infestation in single and doubled hives they recorded are shown in Figure 3 though it is not clear how the respective colonies were actually managed.

Figure 3 Average Varroa infestation rate of single versus double hives (%). After Cengiz and co-workers. (2019). Note the authors mislabeled the cohorts so doubled hive and single-queen hive mite levels are simply reversed to match their stated conclusion.

A two-queen hive exemplar from Mexico

In an earlier study, Valle and coworkers (2004) compared the performance of single-queen with two-queen hives on the Mexican High Plateau. Their study was undertaken to address problems associated with declining honey yields, the arrival of the Varroa mite and Africanisation of local honey bees. In summary:

The study was similar in design to that of Cengiz and coworkers. Valle et al. also employed ninety two colonies (forty six colonies with one queen and forty six with two queens), the two-queen units being set up in the Floyd Moeller [1976] consolidated brood nest style. They lost many queens but, of the colonies that survived, the two-queen hives doubled honey yields.

Establishment and operation of hives containing two queens, though not overly difficult, requires considerable acumen. Traditionally two-queen hives are established from strong overwintered single-queen colonies, split in early-to-mid spring to arrest swarming. They are then built and united as two-queen colonies before the main summer honey flows.

Since we need to take full advantage of early fruit flow and regular late spring red box (Eucalyptus polyanthemos) flows we jump start the process by making splits in autumn rather than in spring. We split colonies as the main summer flow concludes, ideally also requeening both units. The colonies are then united – as doubled or two queen hives – very early in spring. The imperative to establish colonies as early as possible is reflected in the timeless maxim of Clayton Farrar (Cale, 1952):

Colony populations must be built before the flow if a crop is produced, not on the honeyflow.

Before launching into how colonies with an extra queen are managed in the presence of Varroa, let us examine their distinctive architectures. As Jeff Ott and Becky Masterman at Beekeeping Today put it controlling mites in hives with giant brood nests will be a big learning curve.

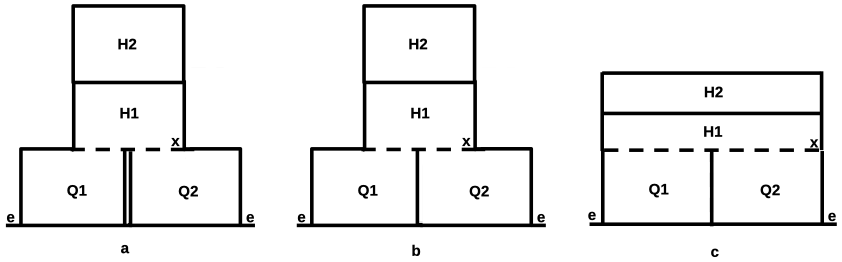

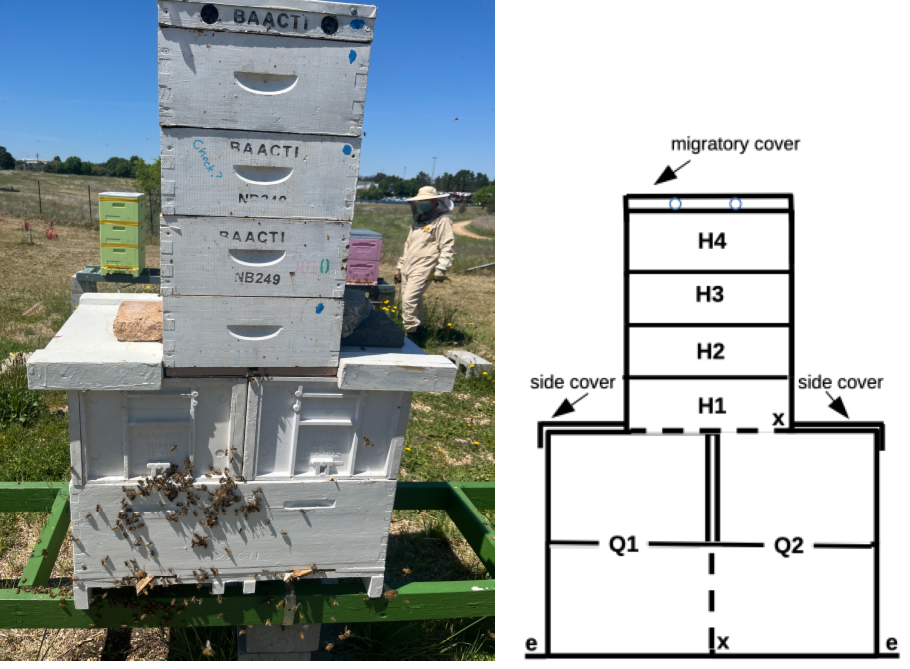

The doubled hive

Doubled hive setups are configured as juxtaposed single brood chambers. This is achieved by either abutting standard brood boxes (Figure 4a) or by equally dividing a long (oversized) brood chamber (Figure 4b and 4c): the colonies are united by bridging honey supers over an excluder. We have operated a 16 F long brood chamber by dividing the chamber with a close-fitting solid follower board (Figure 4b); Elsewhere we have employed a rimmed vertical queen excluder (Figure 5b) in the two-queen style of operation discussed below.

Figure 4 Doubled hives: Q = queen; H = honey; x = excluder; e = entrance:

(a) standard side-by-side hives supered centrally; and less commonly

(b) divided long hives with standard supers; or

(c) divided long hives with coffin supers.

Doubled hives are easily setup and dismantled. If perchance either queen fails a new single-queen nucleus colony can be papered in. Since each brood nest operates more or less independently both can be treated individually to reduce mite loads. In the 2024-2025 season – well prior to arrival of Varroa – we were able to demonstrate building and removal of drone comb (discussed below) by the simple expedient of removing side covers (Figure 4a and 4b) without needing to remove honey supers.

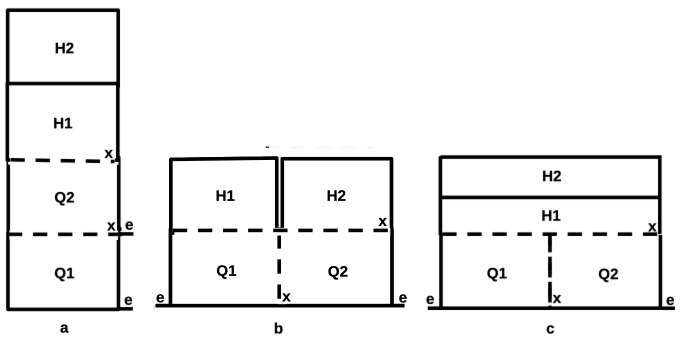

The two-queen hive

Modern two-queen hives are operated with brood nests juxtaposed (Figure 5). With brood below and honey supers atop they are managed much as single-queen hives are.

Figure 5 Two-queen consolidated broodnest setups: Q = queen; H = honey; x = excluder; e = entrance:

(a) tower or vertical hive with standard honey supers;

(b) horizontal long hive with standard honey supers; and

(c) horizontal long hive with coffin honey supers.

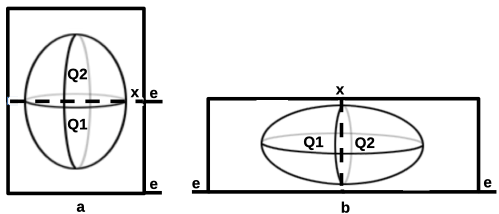

A defining condition of these consolidated two-queen hives is the formation of large and thermally efficient ellipsoid broodnests (Figures 6a and 6b).

Figure 6 Ellipsoid broodnest architecture of consolidated two-queen hives: Q = queen; x = excluder; e = entrance:

(a) vertical stack hive; and

(b) horizontal long hive.

Major advances in the development of two-queen systems were made between the 1930s and 1960s, but were predicated on keeping the individual queen nests well apart (Figure 7a and 7b). With the common tower arrangement (Figure 7a) further supering between the brood nests as well as above the upper brood nest was a difficult endeavour, one too complex for sustained Varroa surveillance and treatment, while the flanking horizontal setup (Figure 7b) has proved to be thermally inefficient and ill-suited to all but tropical climes. Bees can only thrive in well insulated horizontal hives, Horr (1998) noting disparagingly:

The long hive is no longer a bee hive, but may become a recycled planter box with a glass top for early spring or winter vegetables. I cannot say it did not work, the bees did fine but the beekeeper came up short of a crop. There is no way I know of to economically keep a horizontal three-hive body colony of bees…

Likewise Émile Warré (1948), singing the design merits of his hive with built-in top-insulation, emphasises the importance of minimising the hive cover surface area and of having a thermal blanketing store of honey above the brood nest:

In winter, there is no risk of the bees getting cold, provided that the stores are above the cluster of bees.

We can also note that a common variant of the original two-queen hive (Figure 7c) has been employed to accelerate the establishment of a new queen, to evaluate the calibre of a newly raised queen or more routinely to establish a second queen.

Figure 7 Historical disjunct two-queen setups: Q = queen; H = honey; x = excluder; e = entrance; ds = double screen:

(a) original Farrar hive, typically with many supers above each brood nest;

(b) uncommon Leroy Bell duo horizontal long hive centrally supered; and

(c) common starting setup also for accelerated top nuc development for either the two-queen top-bottom setup (Figure 7a) or to initiate the consolidated two-queen (Figure 5a) setup.

Part B Varroa management of colonies with two or more queens

Having closely examined the architecture and essential operational requirements of multi-queened colonies, we can now turn to practical measures that may be applied to control parasite mite numbers.

Doubled hives

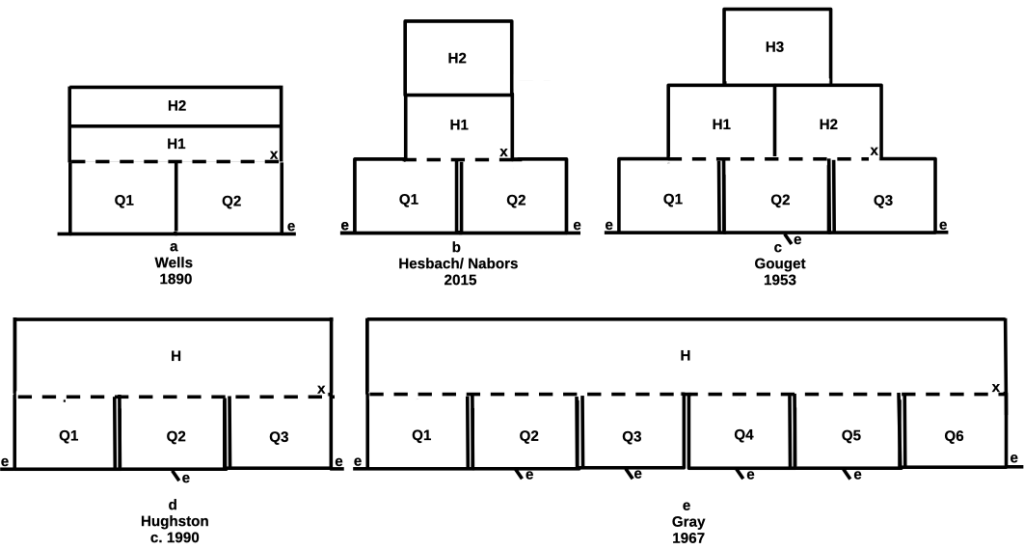

Historical exemplars of doubled and multiple single-queen hives with independent brood chambers and shared common honey storage are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8 Historical multi single-queen hive setups: Q = queen; H = honey; x = excluder; e = entrance:

(a) George Wells doubled hive with perforated division board and coffin supers;

(b) Bill Hesback/Ron Nabors doubled hive using standard supers throughout;

(c) Charles Gouget’s tripled hive using standard supers throughout;

(d) Stringy Hughston’s tripled hive using standard brood chambers and coffin super(s); and

(e) Ken Gray’s sextuplet hive using standard brood chambers and coffin super(s).

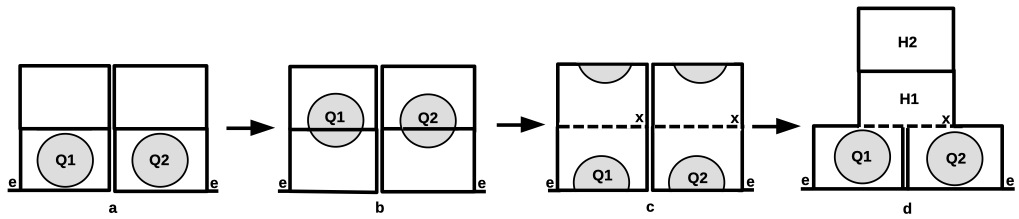

Doubled hives are best setup by splitting strong colonies in autumn (Figure 9a) and uniting them in early spring (Figure 9d). However the vertical hive split (Figure 7c) is the most widely practiced method of establishing a second queen when instigated in spring.

Figure 9 Alternative doubled hive setup: Q = queen; H = honey; x = excluder; e = entrance:

(a) a colony split late in season, ideally requeened and built to overwinter as abutted single colonies with stores;

(b) by late winter queens and brood nest migrate into upper chambers;

(c) each broodnest is reversed shaking bees down below an excluder in very early spring; and within a few weeks

(d) brood nests fully reestablished are united and built as a doubled hive for the flow.

If any single brood chamber in a doubled hive operation proves to be ‘Varroa susceptible’ or as already noted fails, it can be removed and replaced by papering in a ‘Varroa controlled’ support nucleus colony.

With the approach of autumn and winter both doubled and two-queen hives are collapsed to abutted single-queen hives or consolidated to form single-queen hives but left with good stores. All queen excluders are removed and the brood nests are simply united, the better queen normally prevailing. Alternatively, if the colonies are exceptionally strong, they may be simply split. Further brood chambers can be checked for mite levels, where needed treated, at both the setup stage and during the later season colony dismantling process.

Mite control employing long acting arachnicides, oxalic acid-glycerine or flumethrin (Bavarol) strips with or without honey supers on would appear to be the best general treatment. Special attention paid to mite control, after removal of the crop and collapse of colonies to single-queen hives, is essential if they are to successfully overwinter.

With doubled hive operation, mite control can – in principle – be effected at any time during the whole year as each brood nest acts independently of the other. With the typical side cover arrangement (Figure 9d, see Figure 8 for side cover detail), these can be removed, drone comb can be inserted and mite laden drone brood removed at three weekly intervals.

Two-queen hives

In the historical context two-queen colonies, though difficult to manage, way outperformed equivalent pairs of single-queen colonies. Under normal flow conditions they produce rivers of honey. Eva Crane (2002) reporting on Don Peer’s famed Canadian two-queen hives, signalled that they were bringing in 20 kg of honey per day. Ron Miksha (2001) visiting the same outfit observed:

We stood on cold concrete in near darkness, facing row after row of neatly painted honey drums, Don Peer and I. Don pointed to a label: ‘Water White, 16.6%, moisture 664 pounds’: three hundred forty two barrels of water white honey. That was the season’s gathering: a quarter of a million pounds [133 tonnes] of honey from around 1000 two-queen hives.

Closer to home, Frank Derwent a beekeeping pal operating a horizontal four-queen hive over the poor summer season of 2022-2023 obtained half a tonne of honey. In theory, colonies with two or more queens – well managed to control mites – should easily outperform equivalent single-queen colonies. However how mites will behave in an oversized broodnest is by no means clear.

While Farrar’s maxim was always to build for the flow, not on the flow, in the two-queen system of beekeeping there is always the imperative of avoiding overproduction of bees. Since idle bees consume precious stored honey and pollen, and since excessive amounts of brood provide a fertile breeding ground for mites, it makes sense to curtail brood production once the main honey flow is under way.

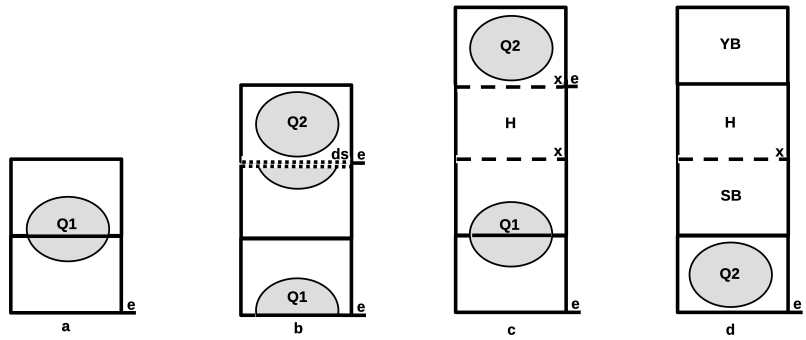

In the late 1940s Winston Dunham (1947, 1948) published full details of a distinctly new two-queen hive arrangement, the Ohio modified two-queen system (Figure 10). He realised that brood development might best be cut back once the honey flow had commenced. He used two queens to build his colonies to maximum strength by the commencement of the main flow, then removed one queen eliminating the difficult process of managing two queens during the flow. He maximised the number of foraging bees at the same time limiting brood rearing in stating:

First, it is essential to understand the difference between the standard two-queen system and the Ohio modified two-queen system. The standard two-queen system utilizes two queens at least during a part of the building-up period and throughout the harvest period. During the harvest period supering involves going through the colonies every ten days and supering the lower and upper units, which are each headed by a queen. This system is best adapted for a region characterized by a long honey flow, and represents an intensive type of beekeeping, where maximum yields of honey are harvested.

The Ohio modified two-queen system embodies the use of two queens in a colony during the building-up period; then reducing of such colonies to a single-queen system, during the early part of the clover flow; and the arrangement of supers at this time, so that top supering is necessary only during the remainder of the harvest period… The fact that the colony is reduced to a single-queen system, when the equipment is light in weight, insures rapid manipulation and makes this system practical to the honey producer…and that super manipulations are completed at this time, except for later top supering.

The challenge of Varroa control in colonies with two queens, either in the double hives or in the two-queen mode of operation relates, in part, to the large amount of gear employed and to the overwhelming number of bees. In the past I have operated colonies with as many four brood boxes and up to as many as six full depth honey supers: Dunham’s system, at least, makes Varroa treatment during the honey flow far more feasible.

Figure 10 Winston Dunham’s Ohio modified two-queen system: OQ = old queen; NQ = new queen; H = honey; SB = sealed brood; YB = young brood; x = excluder; e = entrance; ds = double screen:

(a) overwintered strong double hive with brood moving to upper chamber;

(b) brood chamber reversed and a new queen is introduced with some stores and brood above a double screen;

(c) double screen is replaced with an excluder to form a two-queen colony, supered as needed and built for the flow; and

(d) the new queen is moved to the bottom board to effect requeening while the old queen is removed at the commencement of the flow. Excess brood is placed strategically above brood to draw bees up to start honey storage and to keep the new queen laying well.

In a much earlier scheme, Medicus (1910) also built his bees to maximum strength using two queens. He and others like Ellis (1908a, 1908b) migrated their bees together with sealed brood – but with only a single queen – to gather honey from the late flowering ling heather (Calluna vulgaris). We are fortunate in having detailed records of their setup and operation (Figure 11).

Figure 11 Medicus scheme using two queens to build bees, switching to single queen operation, for the late heather honey flow: ex = excluder; w = wire screen:

(a) new queen established with brood and stores above a wire screen;

(b) excluder replaces wire screen to establish two-queen colony;

(c) lower brood chambers reversed and colony supered for summer flow:

(d) colony reorganised and summer crop removed;

(e) one queen offset with young brood in home apiary; while

(f) single queen colony with most of the bees as well as sealed and emerging brood and empty drawn comb is migrated to the heather.

So we see that in both two-queen schemes hive operation during the principal flow is greatly simplified if one queen is removed for the actual flow assuming of course that multiple flows are not anticipated. Hive manipulation to augment brood presents a chance to check mite levels and treat using a long acting miticide. Further we see that with two-queen hive management, where brood boxes are juxtaposed, mite managment is straightforward and can mirror that of mite control in single-queen hives.

Since two-queen colonies require intensive management, success in operating them with Varroa will also come down to additional effort to control mites. Ready access to brood, and hence treatment, in the horizontal two-queen configuration (Figure 12) setup is a good starting point. We practised raising removable drone comb over the pre-Varroa season of 2024-2025.

Figure 12 A recent setup of horizontal two-queen hive, Jerrabomberra Wetlands apiary 19 October 2024 depicting removable telescopic side covers. Note double broodnests for each queen, a common requirement for brood boxes containing less than nine-frames.

Once the major flows are nearly over colonies not already split should be broken down not only to avoid overproduction of bees but also to make bees amenable to mite surveillance and treatment. In the two-queen setup end of season operational requirements are more nuanced than those for doubled hives. With doubled hives colonies are simply set apart. Since, however, two-queen colonies will revert to the single-queen condition during any period of dearth and certainly of their own accord in autumn, it is best to anticipate this eventuality and remove one queen or divide the hive. Overall we are reminded that multi-queen colonies are never managed for the purpose of maintaining an extra queen or queens. Rather, well managed, an additional queen produces more workers and minimises swarming potential.

Left in limbo

Where does this all leave us? It seems that running colonies with an extra queen, assuming good management practice, will offset the loss of productivity occasioned by parasitism for the following reasons

- several, usually two, queens have the potential to raise more bees than does a single laying queen signalling a reproductive advantage relative to that of mites;

- spitting of hives is standard practice for establishment of a second queen and is a well known mite suppression strategy. For example spitting of overly strong colonies at the end of the season, treating each of them to reduce mite loads and feeding them well will, of itself, improve their overwintering potential; and

- nuanced management of colonies with an extra queen, for example maximal removal of mite loaded drone comb, is potentially more sustainable than with colonies dependent on a single laying queen.

Let’s look at a few examples. Conrad (2025) describes a strategy to control Tropilaelaps mites, one likely of general mite control application, involving an asymmetric colony split. Each unit becomes broodless so mite control can be very effective:

Another easy way to take advantage of this Achilles heel [brood cycle interruption] is to simply divide the colony, moving all brood combs and adhering bees into a new box and leaving the queen and broodless combs and bees in the original hive. The queenless colony will begin rearing a new queen, but the resulting interruption in brood production will kill off all the Tropilaelaps mites. Meanwhile, the mites will also all die out in the queenright half of the hive since there will be no brood to feed on and it will be approximately three days before any new eggs the queen lays can hatch and form larvae that the mites need for food. If this process is carried out at the end of the nectar flow, no honey production need be sacrificed and colony numbers can either be expanded by keeping the newly created hives or hive populations can be maintained by recombining the colonies.

A similar scheme to reduce both Varroa and Tropilaelaps levels, splitting single-queen colonies, has been proposed by the US Department of Agriculture (de Guzman et al., 2016, 2017). Their scheme makes use of a Cloake board, a multi-entrance division board, keeping all bees on the one stand:

To avoid destruction of brood while at the same time allowing continuous brood production, the same outcomes can probably be achieved by using a Cloake board placed between two hive boxes. This consists of a queen excluder mounted to a wooden frame with grooves that allow for a removable sheet of thin metal (Cobey, 2005a, 2005b). The metal sheet is installed to separate the upper (containing emerging brood frames only) from the lower box (containing the queen and precapped brood frames), and also serves as a temporary floor with an upper entrance. The lack of suitable hosts in the upper box will lead to starvation and death of Tropilaelaps mites that emerged with the bees. After one week, bees in both boxes can be reunited by removing the metal sheet. The queen excluder prevents the queen from laying eggs in the upper box. This process can be repeated when capped brood in the lower box is about to emerge.

These schemes, effective in suppressing mite reproduction in single-queen hive operations are best suited to end of season management when colonies have done their seasons’ work. Other brood break systems, notably those outlined by Büchler et al. (2020) and Uzunov et al. (2023) applied after the honey flows, will return colonies to their single-queen condition, at the same time dinting mite numbers.

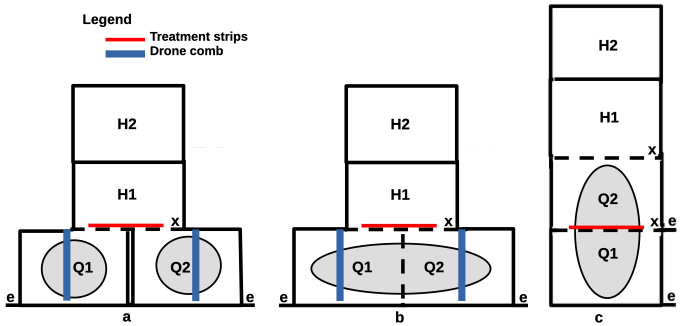

Most mite control procedures are too disruptive to be applied during the double hive or two-queen hive phase of operation: they require removal of many honey supers and safe handing of two or more broodnests. However with some horizontal setups (Figure 13a and 13b) treatment with oxalic acid-glycerine or flumethrin strips, both permitted with honey supers in place, should be straightforward and effective though handling the standard tower two-queen setup (Figure 13c) will be more challenging. The spring of 2024, long before mites arrived in our district, provided us opportunity to trial mass drone production as a prelude to drone-mite trapping. Since we were monitoring drone comb production, and were keen to observe the effect of uninhibited drone production, we left the combs in place and were not surprised to observe colonies with exceptionally high drone numbers. Installing and removing far more drone comb that could be sustained by single queen colonies may prove be a very effective way of interrupting mite production (van Engelsdorp et al., 2009).

Figure 13 Doubled hive and two-queen hive treatment options during buildup and honey flow: red = miticide strips; blue = removable mite laden brood, e.g. drone brood; e = entrance; x = excluder; Q = queen; H = honey super:

(a) standard doubled hive setup;

(b) atypical two-queen hive setup in oversized brood chamber; and

(c) standard two-queen setup.

These musings pose further questions, mainly the problems that Tropilaelaps will some day present. Tropilaelaps is widely viewed as presenting a threat much greater than Varroa largely because of its extraordinary reproductive potential (de Guzman et al., 2017; Burlew, 2023; Conrad, 2023). It takes only a week for an egg to develop into an adult mite. For a colony infested with vanishingly low levels of Tropilaelaps mites and a typical number of overwintered Varroa mites, Varroa numbers may grow quickly but then be overtaken by Tropilaelaps, a double jeopardy. Any marginal protection against Varroa afforded by an extra laying queen may be quickly lost if Tropilaelaps comes into the equation.

Perhaps we should look beyond Tropilaelaps mercedesae and Tropilaelaps clareae to other phoretic mites including Leptus ariel and a few other suspects such as the phoretic Melittiphis alvearius (Barreto et al., 2004) – that has turned out to be a cosmopolitan kleptoparasite pollen mite – and a furtive genus Blattisocius mites including one, B. keegani,that is best known as a coleopteran parasite but is also found in bee hives (Morales, 1995).

So what does the uncertain record of operating multiple queen hives with Varroa actually tell us? We don’t know. However beekeepers, forced to manage their hives more closely with the arrival of the mite, might well continue to keep healthy productive bees and we might all keep a lookout for new invaders.

Maybe tossing in an extra queen to boost bee numbers could be part of the answer to Varroa.

Readings

Barreto, M., Burbano, M.E. and Barreto, P. (2004). The bee mite Melittiphis alvearius (Berlese)(Acari: Laelapidae) in Colombia, South America. Neotropical Entomology 33(1):107-108. https://www.scielo.br/j/ne/a/fSpnrsY4KCcP9nsfpVPLdVd/?lang=en&format=html

Büchler, R., Uzunov, A., Kovačić, M., Prešern, J., Pietropaoli, M., Hatjina, F., Pavlov, B., Charistos, L., Formato, G., Galarza, E., Gerula, D.,Gregorc, A., Malagnini, V., Meixner, M.D., Nedić, N., Puškadija, Z., Rivera-Gomis, J., Rogelj Jenko, M., Smodiš Škerl, M.I., Vallon, J., Vojt, D., Wilde, J. and Nanetti, A. (2020). Summer brood interruption as integrated management strategy for effective Varroa control in Europe. Journal of Apicultural Research 59(5):764-773. https://sci-hub.sidesgame.com/10.1080/00218839.2020.1793278

Burlew, R. (1 October 2023). A Tropilaelaps primer: what, when, and how bad? American Bee Journal 163(10):excerpt. https://americanbeejournal.com/a-tropilaelaps-primer-what-when-and-how-bad/

Cale, G.H. (June 1952). The effect of the two-queen system on the harvest: An interview with Dr C.L. Farrar. American Bee Journal 92(6):236-237. https://archive.org/details/sim_american-bee-journal_1952-06_92_6/page/236/mode/2up

Cengiz, E.H., Genç, F. and Cengiz, M.M. (2019). The effect of the two-queen colony management practice on colony performance and Varroa (Varroa destructor Anderson &Trueman) infestation levels in honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) colonies. [Bal arılarında (Apis mellifera L.) iki analı koloni yönetiminin koloni performansı ve Varroa] (Varroa destructorAnderson & Trueman) bulaşıklık düzeyine etkisi.] Uludag Bee Journal 19(1):1-11. https://acikerisim.uludag.edu.tr/server/api/core/bitstreams/38b8f1d6-efe0-43cf-b8da-dd732b1fff59/content https://uludag.edu.tr/dosyalar/agam/DERG%C4%B0LER%20PDF/2019/metin_20191.pdf

Cobey, S. (2005a). A versatile queen rearing system Part 1: The Cloake board method of queen rearing. American Bee Journal 145(4):308-311. https://nebula.wsimg.com/b81244acaa22707a2b1d3b91d451e77c?AccessKeyId=95EE9AA7688652D2F900&disposition=0&alloworigin=1

Cobey, S. (2005b). A versatile queen rearing and banking system Part 2: Use of the Cloake board for banking purposes. American Bee Journal 145(5):385-386. https://ia802905.us.archive.org/20/items/CloakeBoardMethodOfQueenRearingAndBankingSueCobey_201905/Cloake%20Board%20Method%20of%20Queen%20Rearing%20and%20Banking%20Sue%20Cobey.pdf [incorporates Parts 1 and 2].

Conrad, R. (1 April 2023). Tropilaelaps: Is this mite really going to be worse than Varroa? Yes and no. Bee Culture. https://beeculture.com/tropilaelaps/

Crane, E. (2002). Making a beeline: My journeys in sixty countries 1949-2000, p.57. International Bee Research Association. https://archive.org/details/makingbeelinemyj0000cran/page/n2/mode/1up

de Guzman, L.I., Rinderer, T.E. Frake, A.M. and Kirrane, M.J. (2016). Brood removal influences fall of Varroa destructorin honey bee colonies. Journal of Apicultural Research 54(3):216–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/00218839.2015.1117294

De Guzman, L.I., Williams, G.R., Khongphinitbunjong, K. and Chantawannakul, P. (2017). Ecology, life history, and management of Tropilaelaps mites. Journal of Economic Entomology 110(2):319-332. https://doi:10.1093/jee/tow304

Dunham, W.E. (March 1947). Modified two-queen system for honey production. Bulletin of the Agricultural Extension Service: The Ohio State University 281:1-16. https://scholar.google.com.au/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Dunham%2C+W.E.+%281948%29.++Modified+two-queen+system+for+honey+production.&btnG=

Dunham, W.E. (May 1948). Modified two-queen system for honey production. [Part of 145 Bulletin No. 281, issued March 1947, by Agricultural Extension Service, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio.] Gleanings in Bee Culture76(5):277-281. https://archive.org/details/sim_gleanings-in-bee-culture_1948-05_76_5/page/277/mode/1up

Ellis, J.M. (1908a). Management at the heather: Wanted better methods––and results. British Bee Journal and Bee-Keepers’ Adviser 36(1379):475-476. https://ia800202.us.archive.org/10/items/britishbeejourna1908lond/britishbeejourna1908lond.pdf

Ellis, J.M. (1908b). Management at the heather. British Bee Journal and Bee-Keepers’ Adviser 36(1384):522-523. https://ia800202.us.archive.org/10/items/britishbeejourna1908lond/britishbeejourna1908lond.pdf

Farrar, C.L. (1968a). Productive management of honey bee colonies. American Bee Journal 108(3):95-97, 141-143.

Farrar, C.L. (1968b). Productive management of honey bee colonies. Apiacta 4:22-28. http://www.fiitea.org/cgi-bin/index.cgi?sid=&zone=cms&action=search&categ_id=55&search_\ordine=descriere

Horr, B.Z. (1998). My intensive two-queen management system means bigger crops. American Bee Journal 138(7):507-510. https://americanbeejournal.com/my-new-two-queen-hive-design/

Medicus (February 10, February, 17 and February 24, 1910). A two-queen system: Some remarks on the adaptability for a heather district. British Bee Journal and Bee-Keepers’ Adviser 38(1442-1444):55-56, 64-66, 75-77. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/83077#page/67/mode/1up

Miksha, R. (August 2001). Honey combing – Selling your gold. Bad Beekeeping Blog. http://www.badbeekeeping.com/chc_04.htm

Moeller, F.E. (April 1976). Two queen system of honeybee colony management. Production Research Report 161, Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture, 15pp., Washington DC 20402. http://naldc.nal.usda.gov/download/CAT87210713/PDF http://mesindus.ee/files/52221134-2-queen-management.pdf

Morales, G. (1995). Reconocimiento de plagas y enfermedades en apiários del suroeste antioqueño. Sociedade Colombiana de Entomología 32:99-113 cited by Barreto et al. (2004) loc. cit.

Uzunov, A., Gabel, M. and Büchler, R. (2023). Summer brood interruption for vital honey bee colonies: Towards sustainable Varroa control using biotechnical methods. Apoidea Press.

Valle, A.G.G., Guzmán-Novoa, E., Benítez, A.C. and Rubio, J.A.Z. (2004). The effect of using two bee (Apis mellifera L.) queens on colony population, honey production, and profitability in the Mexican high plateau. [Efecto del uso de dos reinas en la población, peso, producción de miel y rentabilidad de colonias de abejas (Apis mellifera L.) en el altiplano Mexicano] Téc Pecu Méx 42(3):361-377. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ernesto-Guzman-Novoa/publication/26478373_Efecto_del_uso_de_dos_reinas_en_la_poblacion_peso_produccion_de_miel_y_rentabilidad_de_colonias_de_abejas_Apis_mellifera_L_en_el_altiplano_Mexicano/links/5d921660458515202b757319/Efecto-del-uso-de-dos-reinas-en-la-poblacion-peso-produccion-de-miel-y-rentabilidad-de-colonias-de-abejas-Apis-mellifera-L-en-el-altiplano-Mexicano.pdf

van Engelsdorp, D., Gebauer, S. and Underwood, R. (2009). A modified two-queen system: Tower colonies allowing for easy drone brood removal for varroa mite control. Science of Bee Culture. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/A-Modified-Two-queen-System%3A-%22Tower%22-Colonies-For-Gebauer-Underwood/e6402a20a8f94049b9d5929d90997bfccda1eeb1 https://canr.udel.edu/maarec/2009/02/01/a-modified-two-queen-system-tower-colonies-allowing-for-easy-drone-brood-removal-for-varroa-mite-control-science-of-bee-culture-dennis-vanengelsdorp-shane-gebauer-and-robyn-underwood/

Warré, É (1948). L’Apiculture pour tous (12th edition). Translated as Beekeeping for All by Patricia and David Heaf, January 2007, Lightening Source, UK. http://annemariemaes.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/beekeeping_for_all.pdf