Alan Wade and Frank Derwent

In our December exposé, we introduced ourselves to the mysteries of the bee shed. We described an array of hive dividers that help the beekeeper maintain some measure of control over the complex internal goings on of the honey bee colony. Natural beekeepers eschew the use of such devices, claiming that they interfere with the preordained organisation of the colony. To that extent, at least, not using fancy gear sets natural beekeepers apart from the commercial and most amateur operators.

Western and Asian honey bees nest in a cavity, a hollow tree or a rock crevice. And, by law, managed hives must be operated with moveable frames. For those managed hives one needs boxes (we call them supers) with free-hanging frames though, in top bar frame hives, this may just be a single closed cavity with simple drop-combs reminiscent of images of the single comb hives of the giant Himalayan Honey Bee, Apis dorsata laboriosa.

Of course we also need lids and bases to keep the bees in and pests and the elements out. The exceptions to nested honey bees are the dwarf and giant honey bees that nest in the open, but even these need a roof or a twig to hang from and some protection from the elements.

Little wonder then that in 10,000 years of humans keeping beesi, finding them homes has been a classic case of ‘invention is the mother of necessity’.

Now, getting back to the humble flat dividing hives we started with in December, we now describe the caps, or lids, and hive bases. Lids divide the honey bee colony from the heavens and opportunistic raiders, while bottom boards keep bees away from mother earth, the dirt and often damp floor. We conclude this sequel by describing a few other contraptions called feeders used to artificially supplement the honey bee diet.

Hive Lids

Standard covers

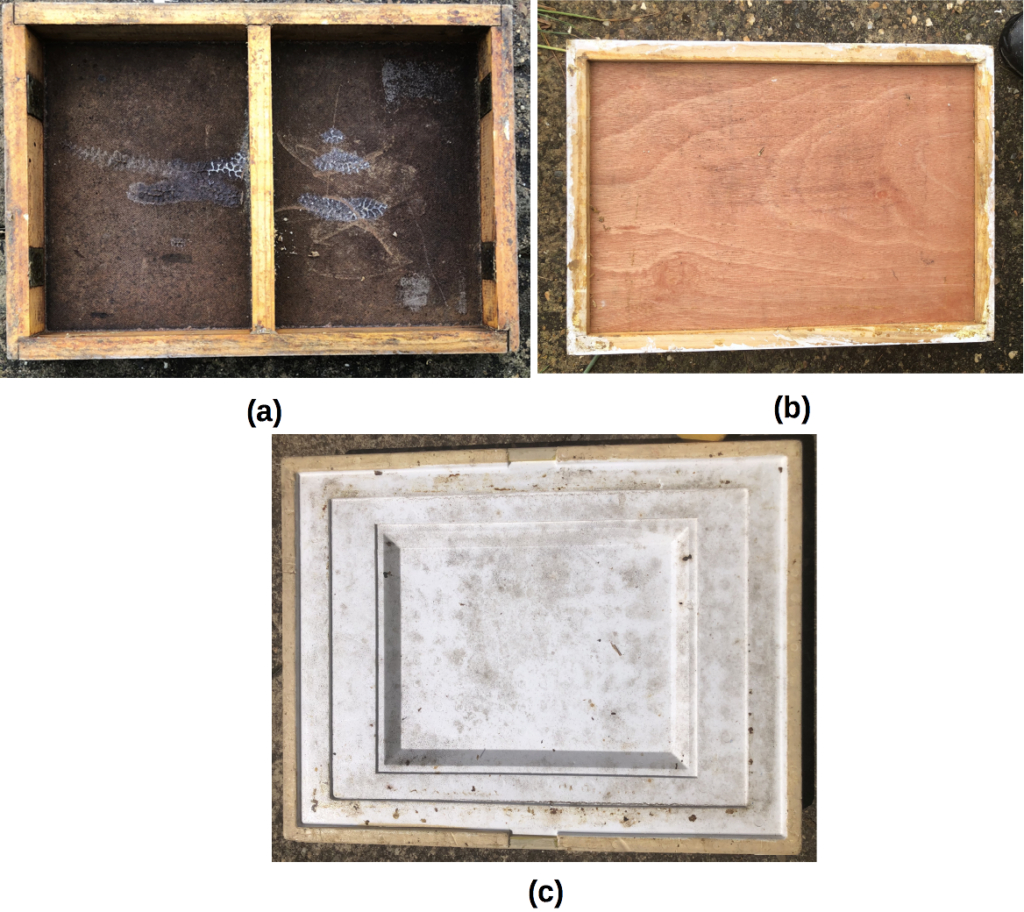

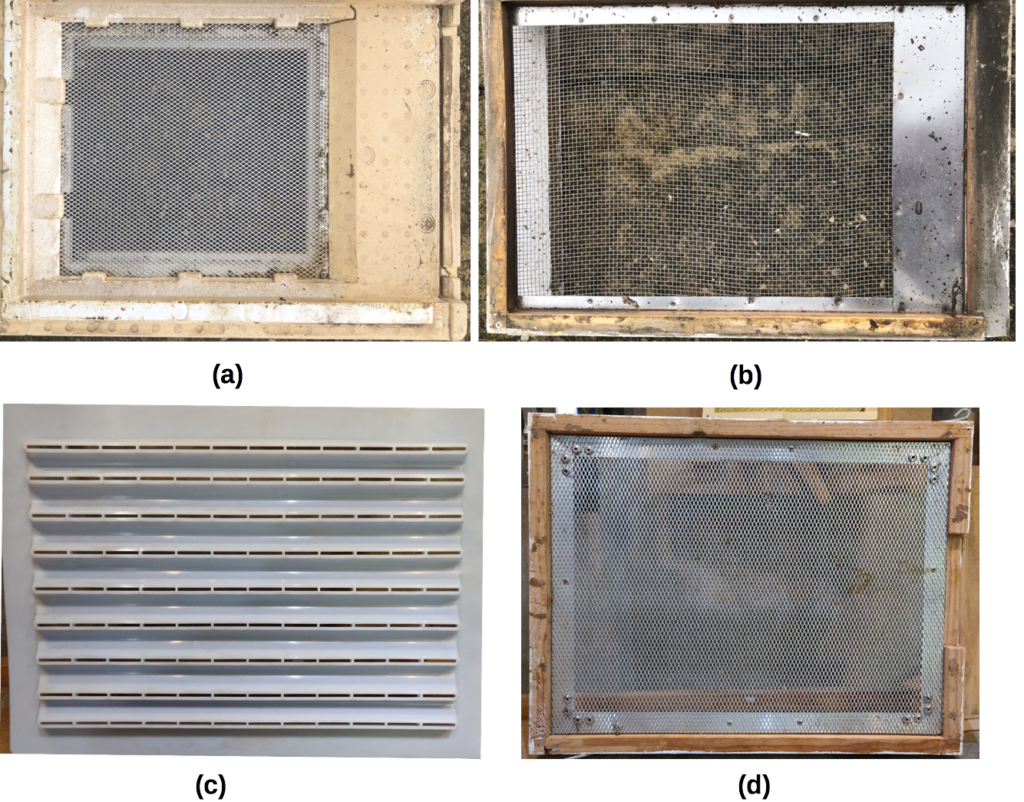

The essential functions of the hive lid are to cap the hive nest and to facilitate ready access to moveable frames. Lids come in a menagerie of designs (Figure 14) but in two distinctive styles:

- the migratory cover (Figure 14a) – so named because these are the lids that commercial beekeepers use transporting their hives from one floral source to the next. These lids sit flush with the sides of the hive boxes so that hives stack together efficiently. The lids provide ventilation and free clustering space under the roof to help prevent overheating when hives are moved; and

- the telescopic lid (Figures 15) – these fit over the top hive body in much the same way as a lid fits over a tea caddy. Most have a flat top, but some have a sloped or gabled roof above to ward off sun and rain. Telescopic lids are not ventilated and are typified by the standard Flow© cover.

The popularity of the migratory lid among Australian hobby beekeepers, those that do not transport their hives, has had an unintended consequence. Bees quickly seal these vents with propolis to prevent winter heat losses.

Figure 14 Hive covers:

(a) standard 8F migratory lid with end ventilation ports;

(b) insulated 8F migratory lid; and

(c) insulated 10F Paradise lid

Figure 15 Telescopic lid for small 3F nuc box

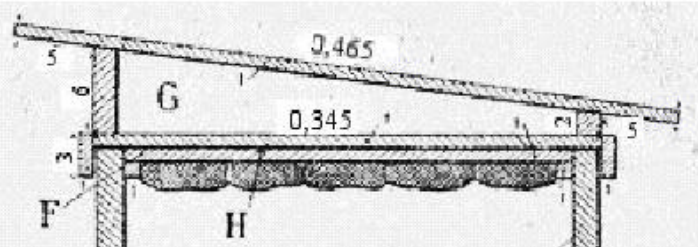

Emile Warré illustrates telescopic lid detail (Figure 16) for a much simplified sloping roof version of his hive cover. We’ve also used telescopic lids (in conjunction with a more standard migratory lid) where super sizes do not match lid sizes to cover exposed brood nest frames (Figure 17).

Figure 16 Sloping roof showing telescopic cover detail in early Warré hive design

Figure 17 Telescopic side frame covers on doubled hive brood nests:

(a) side covers showing side cleats upper and handles lower; and

(b) telescopic side covers in use in combination with central honey supers with a migratory lid on honey supers

Insulated covers

In a natural tree hollow bees ventilate their space vertically venting excess moisture and waste gases through a low side or bottom entrance. They rely on a solid roof and side walls and upper blanket of honey to keep their nest snug. Photos of hives from overseas show there is a strong preference for the telescoping lid style of hive cover. In conjunction with a top blanketing inner cover, this lid seals and insulates the hive better than the migratory lid.

Insulating beehives is by no means a recent innovation. In their bid to banish the icy fingers of winter, higher latitude northern hemisphere beekeepers have either brought their hives into sheltered bee barns or bee houses, wrapped them in heavy duty insulation, or more recently built their hives from insulating materials. Such insulated hives function well over hot summers obviating any need for shade.

Beekeepers running traditional wooden hive furniture can improve colony performance by installing insulating material inside migratory hive lids or by purchasing insulated lids (Figure 14b and 14C) from equipment suppliers.

Émile Warré was an early proponent of incorporating roof insulationii. His colony supers are topped with a box of moisture absorbing and insulating wood shavings, a telescopic cover and a gabled roof (Figure 18a): the natural tree hive nest is encased with a thick wood buffer. The flow hive lacks the insulating top-box but does incorporate an insulating inner cover, a telescopic cover and has a similar closed gabled roof (Figure 18b).

Figure 18 Gabled hive roofs incorporating telescopic cover:

(a) Warré roof structure with wood-shavings insulator box below; and

(b) Flow roof structure incorporating insulating inner cover under lid

Hive mats placed under lids (Figure 19) are employed with traditional migratory lids and can be made of almost any material. We have tried thin ply, corflute, linoleum, tarred insulation foil and carpet squares. We’ve found that insulation foil is chewed out while carpet tends to become heavily propolised. Hive mats are sized to provide bee space along the edges to giving bees access to under lid space. Some mats, such as the Mercer cover, have a central hole to allow bee access to top (inverted tin) sugar syrup feeders housed in an empty top super.

Figure 19 Hive mats:

(a) plywood mat; and

(b) Mercer mat with central top feeder slot

Hive mats help avert burr comb development (Figure 20) but can provided refuge for wax moth and small hive beetle. The older beekeeping literature makes frequent reference to inner covers whose role is quite different to that of the hive mat. Their function is to insulate bees under telescopic hive lids.

Figure 20 Burr comb in migratory lid where a hive mat was not used:

(a) in club apiary 10 October 2020; and

(b) after clearing bees

Bottom Boards

Standard bottom boards

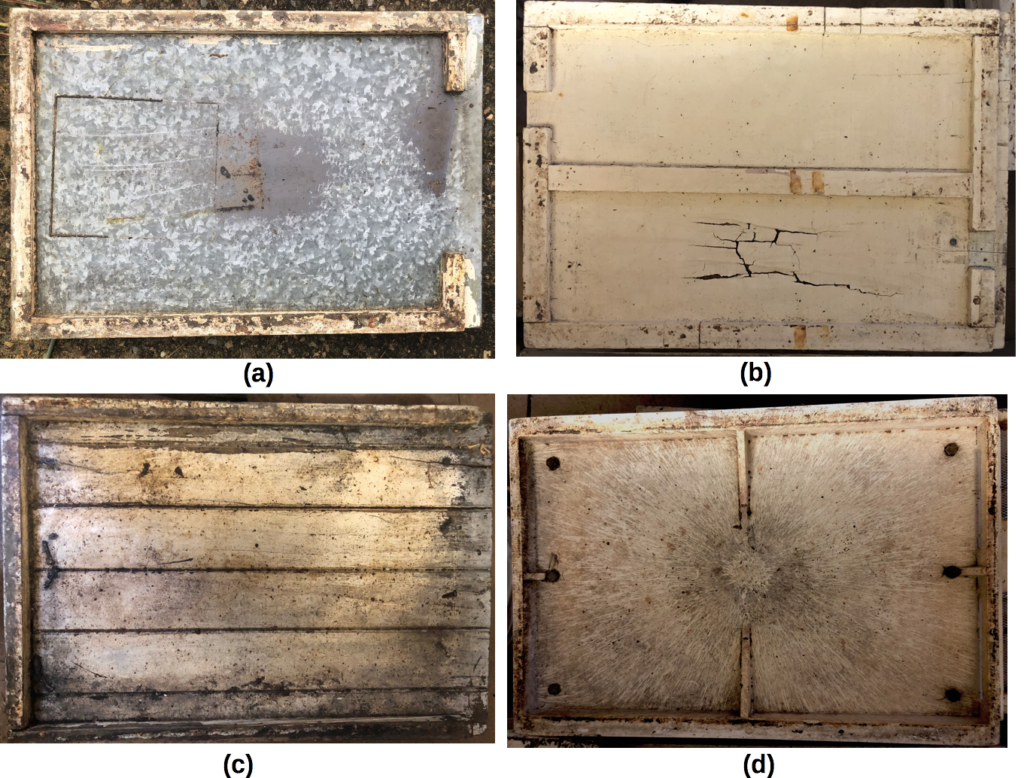

Traditional bottom boards (Figure 21) have an impervious floor to protect the hive from soil damp and pestsiii. The entrance, in wild hives, is small enough to enable the bees to defend themselves from pests such as mice, European wasps and other bees. The hive entrance also serves to provide hive ventilation and is the gateway for incoming honey, pollen, propolis and water and for removal of hive waste materials.

This traditional floor arrangement for managed bee homes ignores the fact that a solid barrier retains hive debris, insect frass, disease material and rainwater or condensate that accumulates at the base of the hive.

The introduction of a bee-proof bottom screen has revolutionised bottom board performance. Use of screened bottom boards has resulted in the elimination of a breeding ground for bee parasites such as small hive beetle and lesser wax moth. Additionally disease-laden debris such as chalk brood mummies and other fungi are largely eliminated. Screened bottom boards incorporating a catch tray and sticky mat are widely employed overseas to monitor and help control Varroa and Tropilaelaps mitesiv.

Figure 21 Bottom boards:

(a) old fashioned 8F galvanised iron bottom board:

(b) two-way wooden 2x4F bottom board;

(c) old fashioned 8F wooden bottom board with wide entrance; and

(d) Parker plastic bottom board with concealed entrances

Ventilated bottom boards

Sommerville and Collinsv demonstrated that screened bottom boards (Figure 22) performed as well as traditional solid bottom board setups and that, since warm air rises, there were minimal heat losses. The key attributes of ventilated bottom boards are their free draining nature, their capacity to avoid build up of insect fras and comb debris and their provision of free ventilation.

In a typical tree cavity hivevi the upper zone of the hive is sealed and well insulated while excess metabolic heat and surplus moisture and carbon dioxide are vented through the entrance normally located near the base of the cavity. This is corroborated by Möbus’s finding that bees establish vertical (up-and-down) air currents and that the bees have a large measure of control over nest ventilation.

Figure 22 Screened bottom boards:

(a) Paradise 10F bottom board;

(b) sliding screen 8F bottom board with provision for sliding catch-tray and a sticky mat for parasite monitoring;

(c) Bluebees slotted bottom board (underside view) insert: and

(d) improvised 10F screen bottom board

Feeders

The requirements for feeding bees was the subject of the April 2019 article Should I Feed my Dog?vii Beekeepers use supplementary feeding to build bees for the honey flow, especially in early spring, to provision bees in times of dearth and to build good stores to tide them over winter.

However, feeding must be conducted judiciously to avoid the risk of honey adulteration. The practice of adding a food colourant to sugar syrup as a tracing agent has considerable meritviii.

A typical colony uses about 120 kg of honey and 30 kg of pollen annually for self maintenance. It stores of the order of 60 kg honey surplus (the beekeeper harvest) but this may be diverted in part to the high energy cost process of swarming. Since bees consume the bulk of the nectar they gather to raise bees, to construct comb and to fuel harvesters, the risks of cane sugar ending up in stored honey are minimal. There is one clear proviso: supplementary feeding should cease once the flow and honey storage commence.

Feeders can be classified into three main types, entrance feeders, frame feeders, and top feeders.

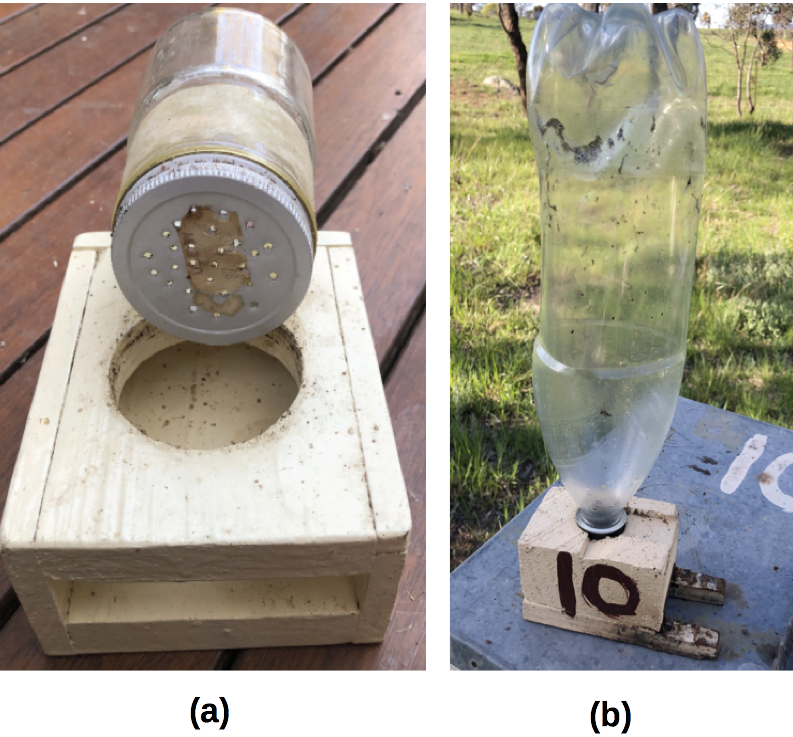

Entrance Feeders The simplest are external Boardman feeders (Figure 23). This style of feeder is popular amongst hobby beekeepers, although the enthusiasm for their use has waned of late. Entrance feeders:

- are portable and simple to fill;

- can be plugged into most hive entrances without disturbing the hive; and

- can be observed for syrup uptake.

Their main detractions are that:

- they deliver only small amounts of sugar syrup;

- their use is restricted in cold weather due to:

- the inadvisability of feeding liquid supplements under such conditions; and

- the limited ability of bees to process chilled sugar water; and

- they are easily dislodged from the hive entrance.

Figure 23 Hive entrance Boardman feeders:

(a) standard feeder delivering minimal sugar syrup; and

(b) a homemade feeder of reasonable capacity

Frame feeders These, as the name suggests, are modified frames that temporarily replace one or several frames. Their main attributes are that:

- they generally have a moderate sugar syrup holding capacity (2 – 5 litres);

- they are fitted inside the hive and thus are not affected by external weather conditions;

- they can be substituted for any standard full-depth frame; and

- they do not encourage robbing.

Their major detractions are that:

- frame space available to the bee colony is reduced; and

- the hive must be opened to refill feeders.

We locate frame feeders immediately under the hive lid and on hive walls to facilitate easy access and to ensure that they are removed quickly once bees commence bringing in nectar.

In an era of moderate austerity, we have used of 2 L powdered milk tins – with perforated press shut metal lids inverted wooden slats housed in an empty super – to feed sugar syrup. We have also very successfully employed home made frame feeders (Figure 24), and punctured plastic bags filled with sugar water placed under the lid. We continue to use them despite the disdain of ‘better educated’ beekeepers.

Figure 24 Home made 2L single-frame feeders:

(a) galvanised iron clad feeder; and

(b) waxed masonite clad feeder

Frame feeders are now available commercially (Figure 25d) though some are wider than the standard Hoffman frame. They are easily refilled but all frame feeders require floating inserts – or dry grass – to prevent bees drowning.

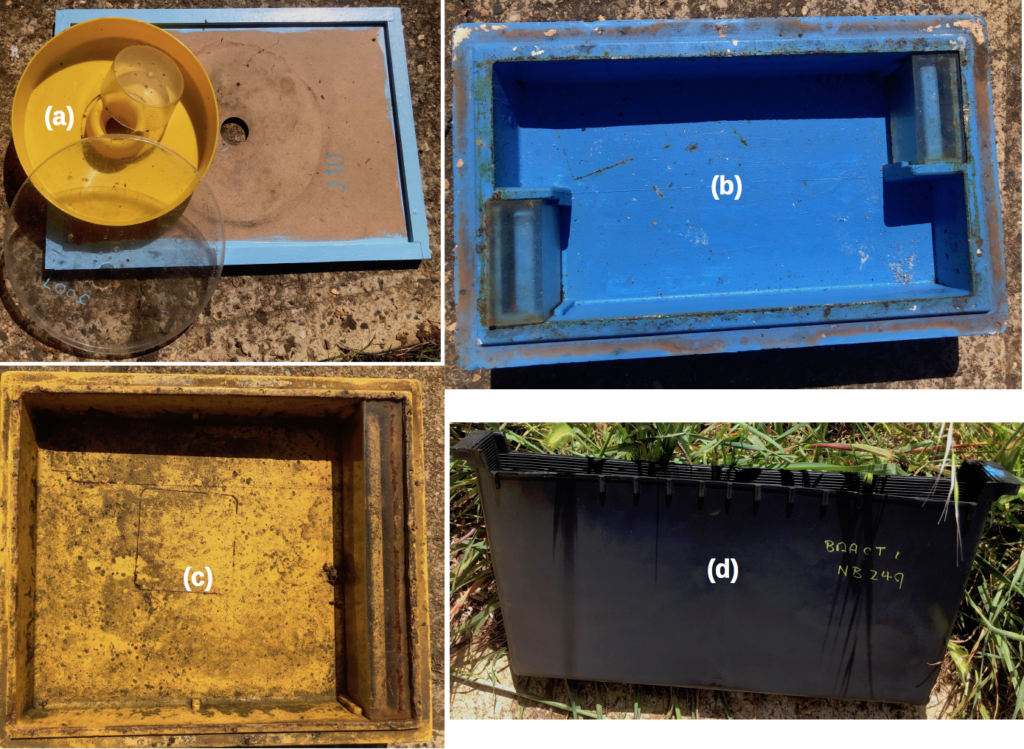

Top feeders With the advent of insulated hive gear, the open tray feeder designs facilitate early season feeding of both pollen and sugar supplements.

Under hive lid top feeders come in a range of styles:

- home made inverted feeder containers – old powdered milk tins and yoghurt tubs with nail punch hole lids suspended over slats of wood in a spare super;

- commercial tray feeders such as Paradise and Technoset-Bee that confine the bees to the hive but provide access to the feed well through guarded ports; and

- plastic tray feeders that closely fit a half depth or ideal super that suit the conventional wooden or plastic Langstroth hive.

The advantages of top feeders come down to the fact thats they:

- they have a larger capacity than other feeder types;

- they are be readily refilled and avoid disturbance to the colony;

- they eliminate shock heat losses associated with lid removal;

- they are easily accessed to observe feed uptake;

- they, at least the insulated types, are not subject to external weather conditions; and

- they eliminate the risk of robbing.

However some top feeder designs are incorporated into a propriety hive system that make them incompatible with other hive types. We have made tray insert top feeders for 10 frame wooden hives and for an apiary Warré hive.

However a variety of commercial in-hive feeders (Figure 25) are now widely available and have much to recommend them. They are easily refilled and have plastic inserts or barriers to limit bee access to sugar syrup wells that prevent bees from drowning. Removal of these inserts allows feeding of dry sugar and pollen or candy made as a dry supplement.

Figure 25 In-hive feeders that can used to feed sugar syrup or dry feed and candy supplements:

(a) under-lid doughnut feeder with feeder board fitting holding about 2L of sugar water;

(b) two-way feeder with common syrup well atop a 2×3-frame Paradise nucleus box;

(c) Paradise feeder of approximately 10L capacity; and

(d) commercial 3L frame feeder

Readings

iCrane, E. (1999). The world history of beekeeping and honey hunting. Routledge, New York.

iiWarré, É (1948). L’Apiculture Pour Tous (12th edition). Translated as Beekeeping for All by Patricia and David Heaf, January 2007, Lightening Source, UK. http://annemariemaes.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/beekeeping_for_all.pdf

iiiSeeley, T.D. (2010). Honeybee Democracy. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ. Chapter 5, pp.99-117.

ivde Guzman, L.I., Williams, G.R., Khongphinitbunjong, K. and Chantawannakul, P. (2017). Ecology, life history, and management of Tropilaelaps mites. Journal of Economic Entomology 110(2):319–332. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/tow304

vSommerville, D. and Collins, D. (2014). Screened bottom boards. Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation Publication 14-061. 48pp. https://www.agrifutures.com.au/wp-content/uploads/publications/14-061.pdf

viSeeley, T.D. and Morse, R.A. (1976. The nest of the honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) lnsectes Sociaux 23(4):495-512. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/269996264

viiSee https://actbeekeepers.asn.au/bee-buzz-box-april-2019/

viiiSuggestion made by club member Jill Robilliard and FoxHound Bee Company https://www.foxhoundbeecompany.com/beekeepingblog/2015/1/6/why-would-i-feed-my-bees-green-sugar-syrup

Be the first to comment