Alan Wade

One of the many challenges faced by the novice beekeeper is knowing when and how to add supers to their hives. A seemingly equally difficult task is deciding when to take supers off again. Common mistakes include keeping the same number of boxes on the hive year round and piling on more supers than are needed. Both are predicated on the hope that nectar will pour in from late spring onwards every year.

The reality is that provision of the correct amount of space is more an art form than a formula to follow. When to add or remove supers depends, in part, on the condition of the bees, particularly the calibre of the queen and the colony population size. But providing more space also depends on floral resources and how long the flow will last. Bees simply won’t draw comb foundation when there is already empty comb or anytime after the main flow. Never try using foundation in autumn.

Some of the best beekeepers I know are also very good botanists. They anticipate the flowering pattern of the important pollen and nectar producing plants, understand the importance of soil moisture conditions and know how long flows last. Nevertheless their efforts are often confounded by adverse weather conditions.

Bee swarms choose snug hollows that are just right: not too much space so the bees will stress out with keeping the McMansion in order and not too little space so that their larder will run out in lean times. Bees cannot upsize or downsize natural cavity space and are programed to choose an optimal size.

Giving the bees the right amount of space in a managed hive is quite another matter, a game of chess where neither bees nor beekeeper get it right all the time.

.A grizzly introduction

To set the scene about how to go about supering honey bees, we need to understand this is partly a problem of beekeepers own making. To get a better appreciation of actual and opposed to imagined colony requirements, we need to visit the bees and ask them how they choose a home.

To help this story along I have chosen a fairy tale that says a lot about the size of an abode, its larder and how much furniture the bees need to satisfy their requirement to survive.

But why are children’s stories so often chosen as a metaphor for life? In Roald Dahl’s rendition of Goldilocks and the Tree Bears we hear thati:

This famous wicked little tale

Should never have been put on sale

It is a mystery to me

Why loving parents cannot see

That this is actually a book

About a brazen little crook…

It is hard not to also conclude that bees may have smothered the brat – as well as the porridge (Figure 1) – with honey where Goldilocks came to a deserved sticky end. For as Dahl further exclaims:

The little beast gets off scot–free,

While tiny children near and far

Shout ‘Goody–good! Hooray! Hurrah!’

‘Poor darling Goldilocks!’ they say,

‘Thank goodness that she got away!’

Myself, I think I’d rather send

Young Goldie to a sticky end.

These aspersions aside, we are first reminded of the inadvisability of running bees in poorly insulated and oversized sized beehives during winter. Give bees too much space and they will find air conditioning (in a Trump-like Mar-a-Lago resort) just too hard to sustain and, in energy terms, too expensive. In all likelihood a colony with an oversupply of bedrooms and storage sheds will fall prey to stress related diseases such as chalk brood, nosema and European Foul Brood, not to mention to Small Hive Beetle and wax moth.

Give them too little space and they will be neither able to make enough stores to overwinter successfully nor resist, in spring, the urge to swarm.

An experienced beekeeper I know well, Ian Wallis, tells me that he shoe-horns his bees so that they ever only have minimal extra space, enough of course to avoid swarming and sufficient to optimise nectar curing and storage in a strong flow, but not too much. As our Goldilocks observed: ‘Not too big, not too small: Not too hot, not too cold.’

Figure 1 Somebody has been at my porridge, and has eaten it all up!ii

Goldilocks as Beekeeper

Given a free choice how do bees choose their domicile and what sized cavity do they select? For millennia beekeepers have been more intent on producing honey than on asking bees about their preference for housing. They hived their bees in the simplest container they could fashion: a clay pot, a hollowed log or, in later times a straw, briar or woven reed skep. By adding glass domes they could harvest comb honey free of brood and no longer had to destroy the hive to harvest honey.

With the invention of hives where comb was attached to slats of wood beekeepers learnt to split hives and selectively harvest honey comb. Eventually came the moveable frame Langstroth hive though Johansson and Johansson indicate that Langstroth, though clearly cognisant of bee space in his design, may not have actually been the first to have discovered itiii. Anyway beekeepers marched to the tune of the cash register. They built multi-boxed hives, often of minimal thickness wood, and as large as bees could fill out.

Thomas Seeley’s championing Darwinian Beekeepingiv, where bees don’t choose large cavities to store honey for humans to collect and where nest walls are both free and thick, is very instructive. Choosing a cavity too small spells their death knell, as an overwintering colony cannot survive on dank cold air. If we go further and observe the biology of many honey bees of African disposition we find that they build small nests, regularly abscond and migrate in sympathy with regional plant flowering patterns.

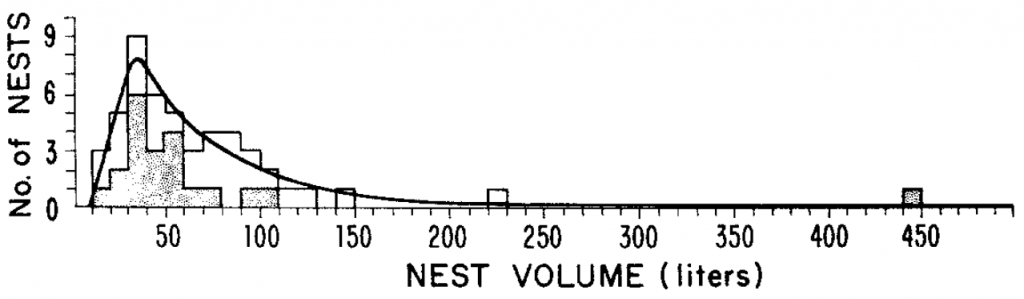

The great lesson of ‘listening’ to the bees – telling the bees is an ancient tradition – is ‘observing’ that honey bee swarms have a strong preference for choosing a nesting hollow of around the single box capacity (Figure 2)v. While we choose to run our bees with select strains of bees bred for production on steroids, we might do so with an eye to more appropriately fine-tuning our hiving and supering practice.

Figure 2 Bee choice of nest size after Seeley

Inspired also by idle correspondence with the editor of The Australasian Beekeeper, Anna Curracan, I was reminded of the common lament of the backyard beekeeper: ‘How do I remove a pile of half full supers of uncapped honey in autumn when, for all intents and purposes, the honey flow is over?’ The answer is that there is really no easy solution. This said, not adding too many supers in a dry year like this one makes common sense.

A super story

In a reality check, we discover that good beekeepers, nearly all commercial apiarists, plan ahead and are a better judge of when to super and when to remove honey than the leave alone beekeeper. To not be able to read bees and to have a measure of how to use beekeeping gear most efficiently would leave the rent-seeking apiarist dependent of an inexhaustible flow of honey rather short. He or she would do better seeking a job stacking jars of honey on supermarket shelves.

Of the important lessons I’ve learnt about beekeeping two stand out. The first is to requeen regularly, particularly to boost the fortunes of an underperforming hive but also to head off spring swarming. The other lesson is to fine tune supering, not least to make best use of available beekeeping gear.

The Goldilocks rule

At one extreme we have seasoned apiarists telling us that piling on supers is good practicevi:

One of the legendary beekeepers of western Canada, Don Peer, a Nipawin beekeeper with an entomology PhD, once told us at a bee meeting, ‘If I were king of the world, I’d make a law that every beekeeper had to own one more super for each hive of bees’.

Don could afford his enthusiasm for supering. At the peak of his beekeeping seasons his bees were harvesting 18 kg of honey a day, so his counsel to super on a large flow – and to remove honey as fast as it comes in – is something all commercial beekeepers rely on to maximise their return. Bees will simply stop collecting nectar if they run out of space to cure and store it. That is a point beekeepers who always harvest their honey at the end of the season should take note of.

But putting on too many supers on hives towards season’s end is always a mistake, This is a sin we’ve all committed and perhaps the most serious error that flow hive operators make, too much gear for the bees to focus on filling their drainable combs. Of course over supering was an even greater problem for section comb honey producers of yore: we might learn from the likes of Eugene Killionvii about reading flows and squeezing bees into minimal extra space, enough of course to optimise nectar curing and storage in a strong flow, but not too much. Remember Goldilocks.

So what is the ideal hive size? Tom Seeleyviii found that in his study area of Arnot Forest in northern New York State wild colonies periodically fail due to starvation, disease or requeening failure. Lifespan for established wild colonies averages about six years but is much lower (~ 2 years) for founding swarms: they have to expend vast amounts of energy building comb. First year winter mortality is consequently high.

Bees know best of course and don’t choose large cavities to store honey for bears or other pillagers of stores. Just the right amount to balance swarming with winter survival and to maximise their existence long term as measured by successful maintenance of wild hive numbers. No expensive house insurance or heating bills thank you!

How and when to super: And when to take supers off

Using insulated bee gear is one answer to the problem of whether to super or not. While bees can regulate their internal environment, if heat can’t escape to warm icy winter night air, that is not the whole story. But given the gear you have in the shed is all you can add to hives, what comprises good supering practice?

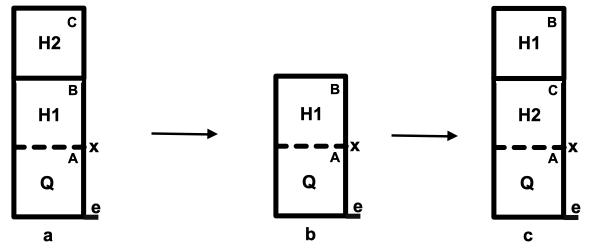

In a big honey flow, it is a good idea to remove and extract as much honey and as quickly as is practically possible. It will increase the crop you take and is good use of gear. In practice this involves under supering of filling honey supers with the stickies you have just extracted (Figure 3). If possible return the extracted combs to the hives you took the honey from – a good disease barrier strategy. And take the opportunity to render poor combs – maybe after returning stickies to hives for a couple of days to clean them up – and to draw new comb as this is when bees draw out foundation best.

Figure 3 Managing honey supers in a flow: Q = queen; H = honey super; e= entrance:

(a) honey supers filling during a flow;

(b) filled top super H2 removed for extraction; and

(c) extracted honey super H2 returned to under super partially filled super H1.

A good rule of thumb is to add more supers than you think you will need, perhaps adding two rather than one super at a time, coming into an expected large flow. Conversely always super very conservatively towards the end of a flow. Late season honey removal presents an opportunity to melt down warped and deformed old comb and to reduce your inventory of stored winter combs.

These rules are hard to put to paper and only keeping bees for years will help you adjudge optimal supering practice. My strategy is to reduce all colonies to doubles for winter – I still run poorly insulated wooden and old Parker style plastic hives: insulated hives are an expensive option the end of a beekeeping career I still run some poorly insulated wooden and old Parker style plastic hives: insulated hives are an expensive option the end of a beekeeping career so I’ve scavenged some 10-frame gear and expect those hives to do better. You can safely reduce hives to as few as six frames if insulated nucleus boxes – as I now do – are used with the proviso they are fed sugar syrup to the hilt at close down.

But now and then one gets caught with too many supers. The best one can do is to leave that extra super on, particularly if it is a shallow or an ideal frame box, perhaps inserting a hive mat over the first honey super so that the amount of space bees need to patrol is reduced somewhat in the hope that mould and wax moth do not afflict the top super. Otherwise remove as many near empty or old and damaged combs as possible and extract the few remaining partially filled combs with mainly capped and ripened honey.

There is, however, one golden rule. Always remove queen excluders at season’s end. They also need cleaning so either pop them in the shed or store then under the hive lid. Bees need free access to all their stores over winter and leaving excluders on will strand the queen and leave her unable to move her brood nest next upper super stores. And the usual cautionary warning: put those flow frames in the shed after removing honey and never leave them on hives over winter.

Apart from clipping grass to keep hive entrances clear, well cared for bees need little or no attention over winter.

iDahl, R. (downloaded 30 April 2022). Goldilocks and the three bears. https://www.roalddahlfans.com/dahls-work/books/revolting-rhymes/excerpt-goldilocks-and-the-three-bears/

iiSteel, F.A. (1918). The story of the three bears, pp.19-24 in English Fairy Tales retold by Annie Flora Steel Illustrated by Arthur Rackham. The Macmillan Co. New York MCMXXII. https://archive.org/details/englishfairytales00stee/mode/2up

iiiJohansson, T.S.K. and Johansson, M.P. (1967). Lorenzo L. Langstroth and the bee space. Bee World 48(4):133–143. doi:10.1080/0005772X.1967.11097170

ivSeeley, T.D. (2017). Darwinian Beekeeping: An evolutionary approach to apiculture. https://www.naturalbeekeepingtrust.org/darwinian-beekeeping

vSeeley, T.D. (2011). Honeybee democracy. Princeton University Press.

viMikska, R. (August 2018). How to predict the honey flow. Bad Beekeeping Blog. https://badbeekeepingblog.com/2018/08/02/how-to-predict-the-honey-flow/

viiKillion, E.E. (1981). Honey in the Comb. Dadant & Sone. Inc, Carthage, Illinois.

viiiSeeley, T.D. (2007). Life-history traits of wild honey bee colonies living in forests around Ithaca, NY, USA. Apidologie 48:743–754. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-017-0519-1