Alan Wade

When George Wells announced a system of running hives with two queens it took the beekeeping community by storm. Lost to the beekeeping world for nearly a century and a quarter, an all-revealing pamphlet has now been unearthed and will soon be published by Northern Bee Books in facsimile form. The pamphlet explains in the simplest terms just how the doubled hive system – fully functional hives with two queens – was discovered.

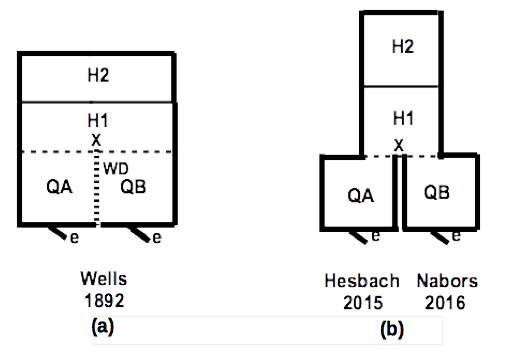

Doubled hives, pairs of single-queened hives sharing common honey storage space, were never thought possible until the late 19th Century. Even today finding apiarists willing to operate hives with extra queens is a rarity.

Early rumblings

Prior to 1890 Wells had established an ingenious scheme for overwintering two queens to the hive. To do this he divided his fourteen-frame full depth Langstroth hive bodies equally with a tight fitting central fine wire screen, each section housing a separate single-queen colony with its own entrance.

To raise the spare queens Wells needed he carefully cut out swarm cells to furnish queen stock for his doubled hives although he also employed captured swarms. These paired colonies fared much better and consumed fewer stores over winter than equivalent single-queen colonies.

From these early investigations, he went on to replace the screen division with a punched reinforced thin sheet of pine board, the so-called Wells Dummy. Wells observed that bees clustered centrally on the dummy board and that they avoided propolising the interconnecting holesi.

Wells autumn preparations paid off handsomely. At the end of winter he united the colonies by removing the central division board deploying spare queens to other overwintered colonies needing requeening or gifting them to local beekeepers. The resulting strong single-queen colonies were in a prime state to build bees quickly on the traditional single-queen hive plan for summer honey production.

An informed discovery

Then in 1890 Wells reserved one of his overwintered doubled hives to enable him to supply a queen that he had promised to a local beekeeper. That beekeeper never fronted and Wells, faced with a very powerful doubled hive, further experimented by overlaying the double-brood chambers with a large queen excluder, quaintly referred to as ‘excluder zinc’. He topped that with a shallow honey super to accommodate the surplus bees. He had figured that bees, having already been acclimatised to a common hive odour, would mix without fighting above the excluder.

To his surprise, the colony proved exceptionally productive, so much so that he piled on more supers and immediately determined that he would never again operate stand alone single-queen colonies. Always capable of taking considered advice, he nevertheless felt obliged to reconsider this decision when challenged about how well his hives actually performed. He patiently trialled his doubled hives against hives headed by one queen, conclusively demonstrating the superior performance of hives with the extra queen. But to make his system work he also had to tackle the age-old problem of swarming, a task he tackled with some elan.

Doubled hive systems: (a) original Wells hive and (b) modern doubled hive using standard gear: Q = queen; e = entrance; H = honey super; x = excluder; WD = Wells dummy

A swarm control strategy

Prior to 1890 Wells had experienced the classic problems of swarming faced by all beekeepers. As George S. Demuthii noted some years later:

Gradually methods were devised for the prevention of afterswarms, and systems of management were worked out whereby the actual working force of the colony is not divided by the issuing of the prime swarm. During more recent years methods have been devised by which swarming is either prevented entirely or the act of swarming is anticipated by the beekeeper, which permits the control of swarming without constant attendance.

By supplying just enough room in the brood nest, but not too much – and by always having young queens at hand – Wells found that he could largely avert swarming and truly optimise colony buildup. To do his he adopted an elaborate scheme of filling out his brood boxes with insulation and dummy frames increasing the space needed as brood emerged pacing each colony to expand and fill out its brood chamber.

These early findings, succinctly and eloquently described in the pamphlet, set the broader scene for the setup of doubled hives, something that side-liners pursue, to get much more honey, to this very day.

iBritish Bee-Keepers’ Association Quarterly Converzatione (October 18, 1894). British Bee Journal, Bee-Keepers’ Record and Adviser 22(643):411-413.

iiDemuth, G.S. (1921). Swarm control. Farmers Bulletin 1198:1-45. https://ia601401.us.archive.org/32/items/CAT87202908/farmbul1198.pdf