Alan Wade and Frank Derwent

When that old fox, Des Cannon1, told us that he once halved the number of hives he owned and got a whole lot more honey we wondered whether there might just be something about keeping bees better. Des has more bee ‘keeping’ tricks up his sleeve than you can poke a stick at, enough to make us recall the old adage:

Look after your bees

And they will look after you.

In the past we have looked at practical means to improve honey production. We have stressed the need for regular disease checks, proactive swarm intervention, optimised spring and autumn nutrition, timely addition and removal of hive gear and checking brood pattern to make sure the queen is laying satisfactorily. Put them together and bee numbers will go through the roof. Strong bees not only produce a whole lot more honey, they help ward off disease and also help control the ravages of hive beetle and wax moth.

But there is another factor that the amateur beekeeper routinely neglects, requeening to keep the egg factory bee young and productive.

………………..

1Des is the editor of The Australasian Beekeeper.

Feature image: Doolittle, G.M. (1899). Appendix to Scientific queen-rearing as practically applied; being a method by which the best of queen-bees are reared in perfect accord with nature’s ways. Chicago, Ills. Thomas G. Newman & Son, 923 & 925 West Madison Street. http://www.bushfarms.com/beesdoolittle.htm

………………..

Colony performance and the queen

Beyond good hive management, colony performance is enhanced by paying close attention to the laying condition of the colony queen. Yes there is one, and only one queen, so if there are only a couple of frames of brood and not too many bees by mid spring, the likely culprit is a failing queen.

Under strong honey flow conditions, queens can wear out in as little as three months, while poorly raised or poorly mated queens may be replaced almost immediately. More typically however, and irrespective of her laying history and pedigree, most queens will go into rapid decline by the time they reach eighteen months of age. For excellent reviews of queen longevity and colony queen replacement check out the wonderfull worlds of Butleri and Simpsonii.

Colony performance is strongly influenced by queen condition. On the one hand her genetic makeup, nutritional condition under which she was raised, mating success and her age will determine her fitness to head up a colony. Extrinsic factors, the size of the nesting hollow, seasonal and weather conditions, and floral resources will strongly influence colony vigour and the tendency of colonies to replace their queen.

Wild bees in a tree hollow will swarm more or less every yeariii in the process replacing their queen and depleting the parent hive population. Direct and simple queen replacement, that is supersedure, can and often does occur without any interruption to the brood raising cycle. Supersedure queens often perform well resulting in a boost to colony performance. Our club records show that, even with an annual requeening program designed to minimise swarming, about half of the total apiary queen stock is nevertheless superseded. Keeping supersedure queens – those unmarked queens you find that have replaced the ones you marked at introduction – is a good idea but keep an eye on their performance and for outbreeding to a cranky strain.

The take home message is to requeen regularly, ideally annually. Below par queens simply cannot lay quickly enough to meet the full potential of a healthy colony: only folklore supports the contention that the queens bought five years ago are alive and doing well.

Getting the best out of queens

We have also covered hive manipulation practices that exploit the full laying capacity of young and vigorous queens, those that keep the bees building at full tilt. Proven measures include reversing brood boxes or rotating sealed brood out of brood nests, judicious brood spreading, providing enough space for the queen to lay and ensuring house bees have ample room to cure and store honey.

Such were the discussions between Ellis and Medicus in the early nineteen naughties. They were exploring measures, including use of two queens, to strengthen hives for gathering valuable heather honey. Their story is the real subject of this month’s Bee Buzz Box.

But first, we thought we might explore the simplest of options for building bees using that extra queen. Nothing fancy, just using a queen that you might otherwise have squished and keeping her in an offset colony to raise extra brood and bees.

Running an extra queen made easy

Some beekeepers adopt a strictly leave alone strategy, an inadvisable practice that sadly many back-yarders adopt. Their hives tend to be headed by indifferent queens. However a diligent beekeeper will not only have good queens in all hives but will maintain queens surplus to needs. Let’s find out how.

Option 1

Say you are requeening a couple of beehives and are wondering whether you might use one or two of the old queens that are still laying well. We say this because novice beekeepers are often reluctant to toss out queens that seem to be doing well but in reality are in their twilight zone.

You can rescue a queen by taking some bees, brood and stores and placing them in a small offset nucleus hive. All you are doing is buying insurance by keeping the old queens – those worth saving – until one is quite satisfied that the new mail oder queens are laying successfully and settled. Alternatively you can adopt the better practice of establishing new caged queens in nucleus colonies, allowing the old queens to keep laying in their parent hives, only later using the new queens to actually requeen.

Either way you avoid the risk of requeening failure as now and then a new queen fails to take. Further you can avoid a break in the brood cycle that sets the parent colony back during queen establishment. After a period of at least three weeks, and with the advantage of having had two queens laying, you can remove the old queen and unite the colonies.

There you have it, a temporary arrangement with two laying queens. And keeping a few nucs year round, requeening them if and as the opportunity arises, is a great way to keep bees. You will always have spares for that colony with a failing queen.

Option 2

But there is another, and perhaps superior, strategy to make temporary use of a second queen. This involves splitting an overly strong hive in mid-to-late spring. This results in the queenless unit raising its own queen. Again you have two laying queens, one in the old colony and the second raised by the bees in the queenless split. The strategy of splitting is most valuable where a colony has become unbalanced – i.e. has too many bees for the amount of brood present – and is preparing to, or is likely to, swarm.

Then, somewhat later, and close to the commencement of the main summer honey flow – when the risk of swarming is over – simply reunite the bees after removing the old queen. The hive, now returned to its single queen status, will have far more brood and bees than would have been possible had the parent never swarmed.

It is a simple recipe for making your bees much stronger while avoiding swarming. You have used two laying queens to produce an exceptionally powerful colony just as it is coming into the main summer honey flow.

Option 3

Another and even more subtle strategy is running two colonies in tandem.

Let’s say you run ten hives as a sideline business. In a sleight of hand you run five pairs of colonies but, with a little extra effort, unite each pair of hives at the beginning of the honey flow. The spare queens, kept in nucleus colonies (or in small hives), can be employed at the end of the season to rebuild hive numbers by splitting still strong populous hives.

We’ve already learnt that a powerful united colonies will produce much more honey than equivalent pairs of single colonies. However you must time the uniting and splitting of hives well, make good any losses and have a clear plan of action if things go awry. The reality is that, with a little extra skill, you will have traded getting more honey against some extra effort.

Doubled hives

Not surprisingly there are many other ways to take advantage of an extra queen. The George Wells’ doubled hive is a good example. Back in February this year we examined his approach, boosting bee numbers early to bring in fruit blossom honey.

Wells’ success lay in building bees in separate back-to-back colonies starting in autumn by splitting strong colonies and setting them up with young queens. The result: colonies came away very quickly in early spring.

Like myriad other schemes, Wells exploited the laying power of two queens combining the workforce to produce record breaking crops.

Two-queen hives

Last month we learnt how the enigmatic E.W. Alexander achieved the seemingly impossible feat of running colonies with two or more free-ranging queens. His hives became exceptionally strong, but his beekeeping skills vastly exceeded most of those of his American contemporaries.

At the same time two Scottish beekeepers, Ellis and Medicus had begun searching for ways to greatly boost colony strengths to cash in on the heather honey flowiv. In gentlemanly exchanges they were shortly to devise a practical scheme to operate two-queen colonies.

The notion of running two-queen hives, using queen excluders to keep queens apart, had already gained currency by 1907v despite Alexander having yet to divulge details of his method of doing so in excluder-free hives. By 1910 Medicusvi had published his account of setting up a two-queen system, in a foreword making an observation on the Wells’ scheme:

.. there has nearly always been misunderstanding as to what is meant by a two-queen system, owing to its confusion with the system advocated by the late Mr George Wells… Mr Wells did not advocate working a colony with two (or more) queens, but advocated giving to two stocks a super, or supers, to which both colonies had access. He profited by the mutual warmth which two colonies in such close proximity must derive from each other, and this enabled them to build up more rapidly in the spring. This advantage was increased during the honey-flow, when, by having a super common to the two colonies, a larger proportion of nectar-gatherers were able to be liberated from home duties.

Medicus then went on to define what constituted a two-queen hive:

…A true double [two-queen] or multiple queen system is one in which a single colony with a single entrance2 has two or more queens laying at the same time, and the workers of which have access to every part of the hive. The queens may be either loose in a common brood chamber, or kept apart from each other by queen excluders.

………………..

2More correctly there may be two or more entrances, one extra one needed to allow drone flight, but the principle that there were two queens in the one hive where all worker bees had free access to every part of the hive is essential.

………………..

Medicus then detailed an ingenious scheme that he and Ellis employed to both supercharge and deploy their bees. Ellis championed this scheme over many years providing regular reports of his forays to chase highly prized upland moors heather (Calluna vulgaris) honey.

Medicus attributed his technique of setting up two-queen hives to the Irish apiarist Cruadhvii. In a modified version of Alexander’s technique, Cruadh had employed an excluder. Like Alexander, Cruadh had found he could establish any number of queens in the one hive. The records show that both Medicus and Cruadh were cognisant of Alexander’s 1907 discovery.

However others who had already been successful in establishing two-queen hives would appear to have done so more by accident than design. A second queen would often appear when, by way of example, the Demaree Planviii brood separating swarm control technique was implemented.

Medicus, acknowledging the respective contributions of other pioneers, had modified the Cruadh system to what appears to be the first ever reliable two-queen system. Medicus succinctly described his establishment of a second queen:

The simplest and safest method of introducing a second queen to a colony was pointed out to me by Cruadh, whose name used to be known to bee-keepers, to whom I am greatly indebted. Having a spare queen, go in the morning to the colony to which this second queen is to be introduced, and remove from it two or three combs of sealed and hatching brood, and place them in a spare brood-chamber division, in the front of which a ½-in. hole has previously been bored. Cage the new queen on one of the combs, and shake in enough bees to care for the brood, but care must be taken that the original queen is left in the original brood-chamber. Having filled up the empty spaces in the original colony with foundation or drawn combs, place over it a frame of wire gauze, and on this stand the nucleus just formed with its new queen. If this manipulation is performed in flying weather the new queen can be liberated with safety on the following morning, as all the older bees will have escaped by the upper entrance and have returned to their old queen below, and only young queenless bees will be built. The combs, however, should be separated on opening the hive, and a few minutes allowed for any of the older bees still left to take flight. Within twelve hours the newly-liberated queens will generally have begun laying.

Colonies were first built in a process of regular brood chamber reversal until, well into the season, a second queen was introduced by establishing a nucleus colony split off from the hive and placed on top at the top above a wire screen. The colonies were then united by simply replacing the screen with an excluder, the two queens working together in a top-bottom brood nest arrangement to form exceptionally powerful colonies.

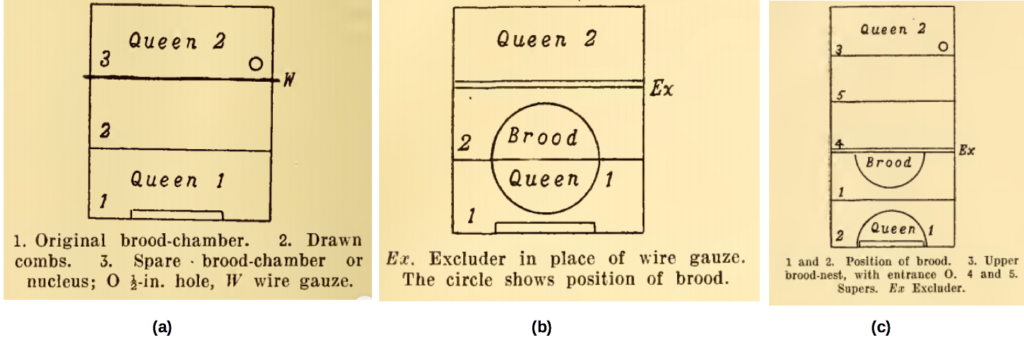

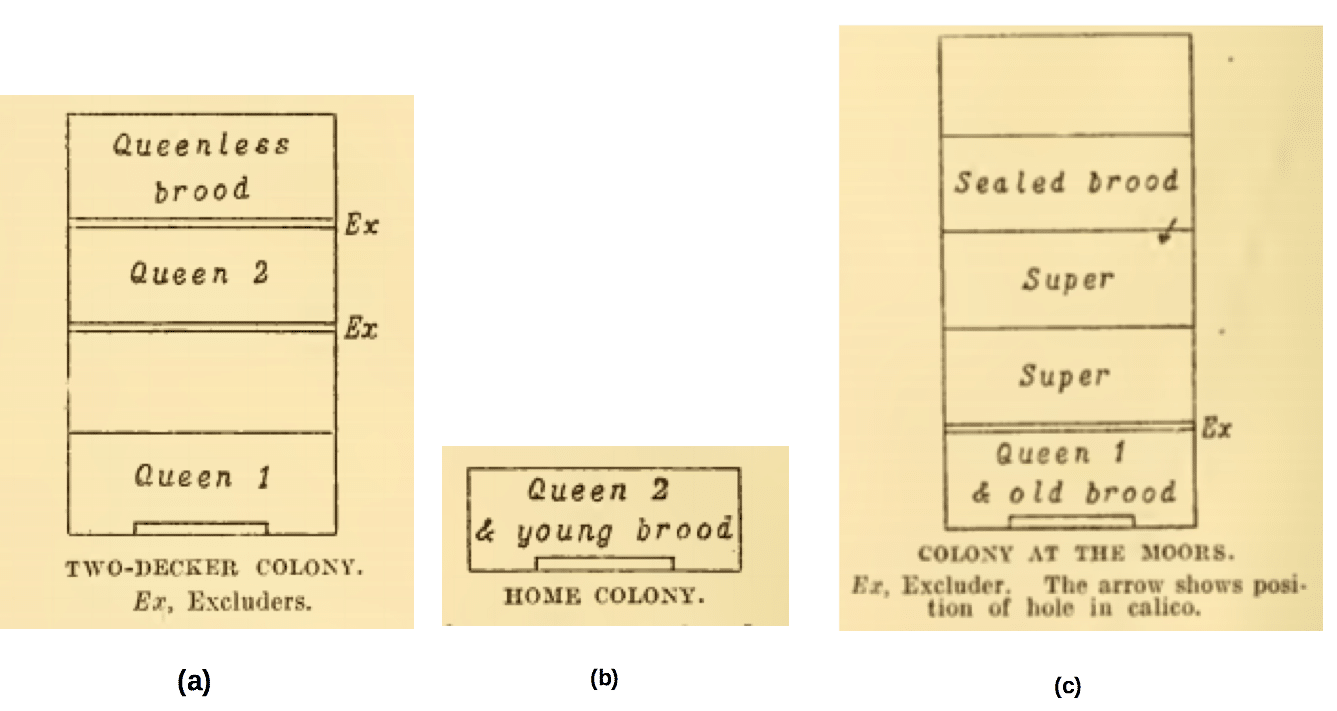

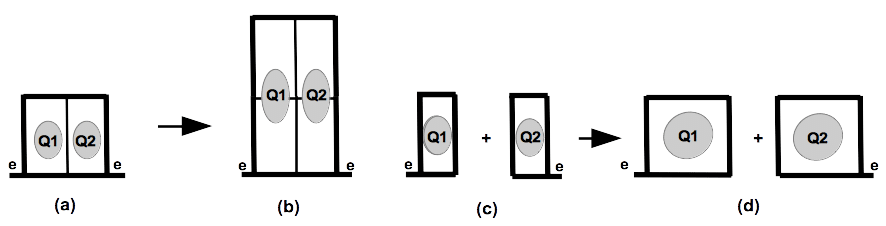

Just prior to the heather flow, the colonies were reorganised and split. The old queen was left in a small colony in the home apiary while most of the bees with sealed and emerging brood, and the new queen, were transported to the moors. Medicus’s 1910 paper also illustrated the finer details of both the initial setup (Figure 1) and its operation (Figure 2).

Figure 1 Medicus two-queen hive set up: (a) second queen established above dividing screen; and (b) colony united and consolidated replacing separating wire screen with a queen excluder; and (c) brood chambers reversed to accelerate buildup.

At the end of the flow, and with the heather crop removed, the now almost spent bees were returned and reunited with their parent hives in the home apiary making them ready for winter.

The destiny of the bees, to stay at the home apiary or to take the track to the moors is reminiscent of Robert Frost’s The Road not Takenix a philosophical reflection on the choices one makes in life:

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

Despite the vicissitudes of Scottish weather, these honey hunters obtained both a clover and heather honey crop. That these enterprising beekeepers had turned to two laying queens made this feat possible.

Ellis’s scheme differed only slightly from that of his early collaborator. In this, Ellis made splits of strong colonies, starting again as Medicus had done, by piggybacking a nucleus with a new queen but using a split board instead of a screen:

Suppose you have a colony occupying two sets of shallow frames. Just as the clover flow begins contract to a single body of ten full frames of brood, supering with racks of sections. Above all place a large board, and on this the box of surplus frames containing small patches of brood with honey and pollen, at the same time providing a small entrance through the hive lift. By the following evening only a few young bees will be left, when a fertile queen can be safely introduced. We have the original stock now in two portions, one making the best of present opportunities, the other building up for the heather campaign.

This scheme was in part made possible by the late honey flow. There was ample time to build bees, bees that here, under Southern Highlands conditions, would only take advantage of the occasional (e.g Red Stringybark, Eucalyptus macrorhynca) autumn flow.

Another heather flow scheme

The Ferris double queen system

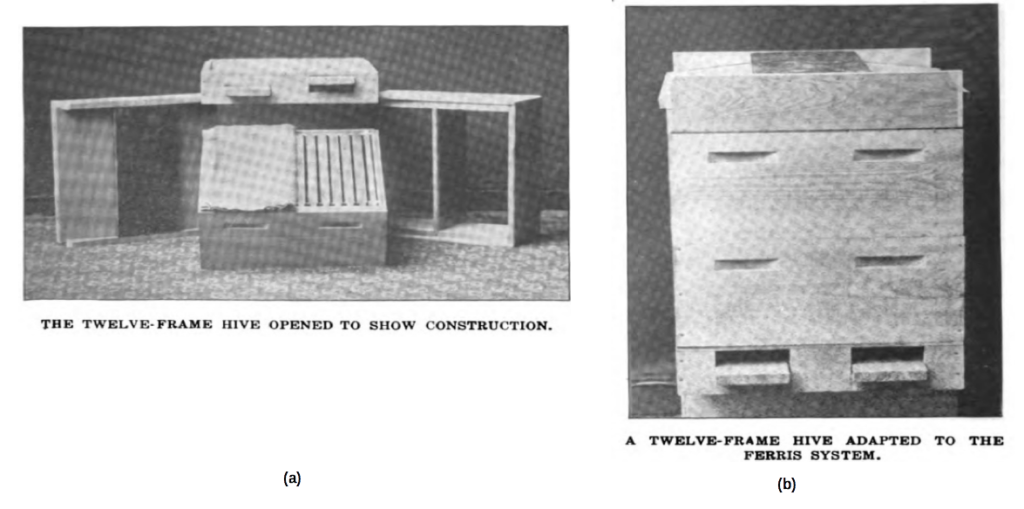

But Medicus and Ellis were not the only beekeepers to harness the laying capacity a second queen to maximise heather honey production. In a scheme long predating their venture, Ferrisx developed a vertically tiered brood nest arrangement colocating pairs of six-frame hives (misnamed two-queen colonies) in standard hive bodies, each hive body divided centrally by a partition board (Figure 3). The arrangement mimicked the original Wells hive – two colonies separated by a perforated board sharing hive odours – except in that the two colonies occupied chambers now separated by a solid board:

Figure 3 Ferris’s double-six, six-frame nucleus colonies: (a) internal structure showing vertical thick division board and foldable mat to isolate each colony; and (b) assembled hive with separate entrances to tiered side-by-side colonies.

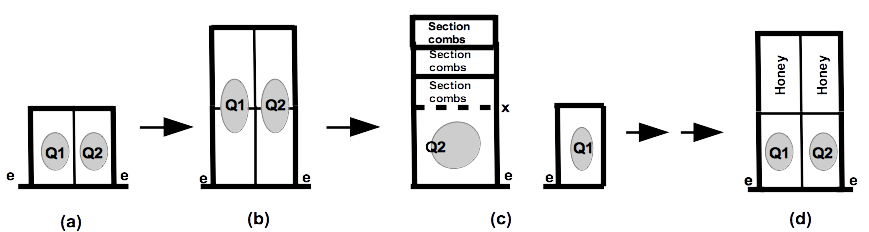

Then, at the commencement of the flow, Ferris first offset queens (removing either one or both queens to inhibit swarming) to small nucleus colonies, then united the bees removing the central division to form a double strength colony (Figure 4). This consolidated all the brood from both colonies to a single full-width brood chamber that were then supered for the honey flow. We have depicted the supers as shallows, fitted out with section combs, as this was both common practice at the time and reflected the premium price paid for comb honey. The Ferris system was developed for general use in building bees for honey flows and does not appear to have been developed by him for the late heather flow.

So while two queens were employed to build abutted colonies, they were never constituted as a two-queen hive. The setup is simply a variant of the overly strong hive split we described earlier where the two hives are united for the honey flow. Then, at the end of the season, the hive is split to reform the doubled-hive setup (Figure 4b).

Ferris provided detailed instructions for setting up the split chamber system – all outside walls were 1½ in. (37 mm) thick so the adjacent colonies were well insulated. The division board was a very sturdy ½ in. (12 mm) thick, reducing the number of frames that the hive body would otherwise take, but it allowed the bees to cluster each side of the separator to share each others warmth.

Figure 4 Ferris double-six system for overwintering bees and building bees for the honey flow: (a) double nuc started by splitting hive into two six-frame nucs; (b) each colony built to strong two two-by-six-frame hives; (c) colony united and supered for honey flow with at least one queen offset to a nuc; and in autumn; (d) main colony split and overwintered as a double colony ready for early spring buildup.

Atkinson’s dual queen, double-six system

By 1921, Atkinson had announced a new scheme for building bees for the heather flow first trumpeting his Masheath hives (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Atkinson’s Masheath Bee Hive advertisements

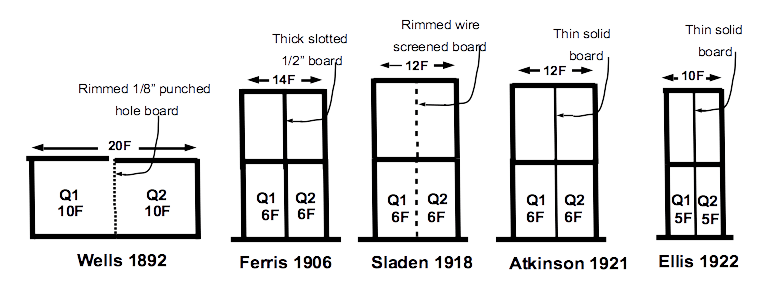

The reality is that he borrowed heavily from contemporary doubled hive schemes developed by Ferris (1906), Sladenxi (1918) and the much earlier system invented by Wellsxii (1892), but pointedly failed to acknowledge their contributions (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Variants of the doubled brood nest – two single-queen – systems adopted by various proponents

While the principles for building bees for the honey flow had a common theme, abutted doubled hives overwintering well and building quickly in spring, their method of use for honey flows varied considerably. For example, the inventive Sladen split hives refining his system to forestall excessive swarming peculiar to the local Ottawa environmentxiii. He controlled excessive swarming by dequeening and allowing both splits to raise emergency queens to maintain the doubled hive set up.

While Sladen supered above the abutted doubled hive over a common excluder – as did Wells – Ellis (and presumably others) united bees just prior to the flow transferring brood to one large super to inhibit the tendency of bees to store honey in the brood nest. The adaptations to different buildup and flow conditions signals the need to read local climatic and seasonal to maximise the benefit of schemes employing two queens.

Atkinson was soon to propose an entirely new scheme for the honey heather flowxiv. He titled his system The dual-queen work—the double-six system.

Atkinson’s instructions, apart from a rambling account of the dual queen setup, require considerable disambiguation, so much so that Ellis sought explicit clarification of his schemexv:

The inventive genius of Atkinson has made this possible by the simple expedient of using two five-frame stock boxes, one above the other, in place of the usual ten-frame brood chamber, reverting to the latter during the actual honey flow only.

Personally, I consider this principle of adjusting the depth and shape of brood chambers is a most valuable feature, and hope Mr Atkinson will let us have some luminous contributions on the subject.

As we have noted, Akinson, for ever the entrepreneur, was never shy to promote his waresxvi. In announcing his scheme he rather disingenuously stated:

In the working out of the system and the handling of the colonies there is a wealth of detail I wouldn’t dare to expect the editors to find space for. To get over the difficulty readers can help themselves by taking advantage of the offer in the advertisement column of the loan of typescript copies of my Cambridge lecture (1920), which goes fully into the dual-colony system and its hive.

He promptly advertised his lecture notesxvii, noting that they would detail his method of operation:

Double-six system, dual-colony working. What it is, and how effected. Typescript copies (24 pages) of Cambridge Lecture, 1920, loaned, returnable within one week, 1s., from the author, M. Atkinson, Fakenham.

Ellis brought the double hive scheme, as the Atkinson system, into his repertoire of building bees for the heather flow. A little later he again sought some clarification from Atkinsonxviii, a request to which a response was never forthcoming:

This applies particularly to heather districts, where in the mutual interests of bees and bee-keepers it is advisable to reverse the usual procedure of clover-filled sections, and brood combs, blocked with heather honey. The latter familiar problem is possibly soluble along the lines of dual-queen working in the vertically divided Atkinson brood chambers, and experiments here last August showed the value of a supplementary queen in reducing brood-nest storage to a matter of ounces. Perhaps Mr Atkinson might give us an article on the dual-colony and double-six methods.

However, on close reading of Atkinson’s brief reports and, with the benefit of Ferris’s and Ellis’s illuminative notes, and Ellis experimenting with similar double-five brood chambers, Atkinson’s ramblingsxix, can be distilled to a few key actions.

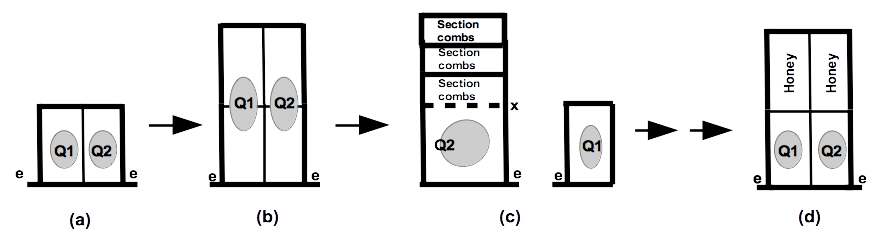

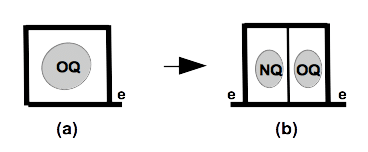

Step 1 – Establishing dual queen nucleus colonies

In Atkinson’s scheme pairs of fledgling colonies were accommodated in the one large super, that is after splitting a colony by slipping in a thin division board and introducing a caged queen to the queenless unit.

Thus set up, the fledgling colonies would share the warmth of their neighbours’ brood nest (Figure 7) – just as Ferris had established – greatly accelerating their development. To avoid drift between the two colonies separate entrances were either arranged at each end of the hive body or, more simply by placing an improvised panel between the adjacent entrances so that field bees could orient themselves left of right.

Figure 7 Doubled nucleus hive (2x6F) on one hive stand: (a) overwintered average strength single with old queen (OQ); and (b) hive divided by central division board with new queen (NQ) introduced.

So far, so good. We have now done away with stand-alone nuc boxes by operating them in standard full-depth gear on the one stand.

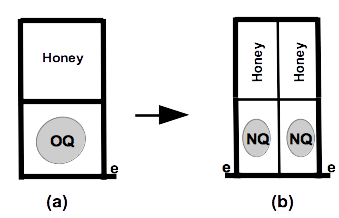

Step 2 – Overwintering bees

Atkinson then came up with the novel scheme of splitting and requeening strong colonies in early autumn placing ‘brood below – stores above’ in adjacent units to overwinter (Figure 7). He arguedxx, we believe correctly, that double-six colonies overwinter much better than an equivalent single twelve frame brood colonies, the arrangement being more thermally efficient and leading to less use of winter stores.

Figure 8 Overwintering bees employing doubled nucleus colony by splitting production hives and introducing an extra queen: (a) single twelve-frame colony; (b) split to two by six-frame’ colonies, so-called dual queen double-six hives

However, as we can attest from years of experience, the dividing board must be very close fitting to avoid queen crossover. Ferris achieved this by using a very sturdy but not overly thick ½ in. (12 mm) division boards that slotted into a 9/16th (14 mm) slot routed into the end walls of fourteen frame boxes (see Figures 4 and 6).

The benefit co-location of two single colonies was realised by early spring when the brood in each colony would have extended into the top chamber. Atkinson’s procedure, when combined with autumn requeening, conferred the additional benefit of avoiding the need to make splits in spring. This paralleled Wells’ success in having strong bees to take advantage of the early fruit blossom flow.

Step 3 – Spring nucleus establishment

Of course the scheme could be extended to the more traditional practice of establishing new colonies in spring, that is from swarms or package bees, again employing a divided brood box (Figure 9a). The rapidly developing dual queen colony was then expanded by adding a second divided super (Figure 9b). Compare this set up with the conventional practice of individual nuclei on their own hive bases.

Figure 9 Spring expansion of double nucleus colony: (a) double-six hive; (b) abutted two by six-frame colonies; (c) conventional separate nuclei; and (d) nuclei expanded to standard brood chambers.

Step 4 – Employing a combined field force

From here, it is unclear as to what Atkinson intended or achieved. It appears that he followed the Medicus-Ellis scheme of employing most of the bees for the honey flow, transferring the brood to a single twelve-frame colony on a standard floor board (Figure 10) and supering above a queen excluder as he advocated moving the queens to small nuclei. This would have forced emergency queen replacement and arrested any tendency of the colony to swarm. Ellis’s arrangement of leaving one queen going into the major flow, when the risk of swarming was largely over, makes much more sense.

The main clue to the Atkinson scheme comes from Ellis’s adaptation:

As regards dual-queen working at the moors, my initial experiment last season was quite satisfactory, and each queen kept her five combs full of brood, so what little heather honey there was all went into the sections The only apparent drawback was that the incoming foragers were inclined to drift largely towards one entrance of the dual-queen hives.

Figure 10 Likely Atkinson hive operation for honey flow:

(a) early expansion of single colonies in early spring;

(b) overwintered or expanded colonies built to full twelve-frame colonies prior to main flow;

(c) reorganisation of combined colonies as a single queen hive with most of brood and bees for migrating bees to major late flow– with optional second queen offset; and

(d) preparing bees for winter – ideally introducing at least one new queen in autumn and redeploying large field force at the end of main flow.

As Ellis further explainedxxi:

Personally I favour dual-queen working, not in the unwieldy Wells hive, but in the ordinary WBC type fitted with Atkinson vertically-divided brood chambers. A colony can be split in two after the honey flow, both lots wintered under the one roof, and, with two queens at work, it is quite possible to have thirty standard combs of brood in one hive previous to the white clover flow. For section-honey production, minus swarming, the combined working forces could be started anew on ten-frame foundation, and with a young queen just as the honey flow began. The original hive, still with its two queens in their respective nurseries, being, of course, moved aside to produce another large force of gatherers for a later honey flow, such as heather.

All that would need to be done would have been to transfer brood in the same manner as Medicus and Ellis had done, taking most of the bees and sealed brood and little else to the flow. Whereas Wells had maintained two queens and used their combined workforce to gather the main crop, it is fairly clear that Atkinson had removed one queen (or both queens) from the equation and utilised the combined the forces of two single colonies to boost the net honey gathering potential of his bees.

In a further tête-à-tête with Atkinson, Ellis sought to clarify his attempts to make use of his, Atkinson’s, doubled hive setupxxii:

Mr Atkinson has misunderstood me. My experiment at the heather was with two five-frame lots side by side in one hive, but supered separately, not working over (an) excluder in a joint super. The Atkinson methods have distinct possibilities, and seem well adapted to meet the needs of those who wish to secure large crops of honey by intensive rather than extensive bee-keeping.

Ellis later gave more detailsxxiii of his scheme to prevent clogging of the brood nest with honey, again hinting that Atkinson might be more forthcoming.

In acknowledging the Atkinson scheme, Ellisxxiv noted generously:

It is not generally known that an ordinary hive of the WBC type is quite adaptable to the dual-queen system and can easily accommodate two ten-frame colonies, each with its own queen, and separate entrance. The inventive genius of Atkinson has made this possible by the simple expedient of using two five-frame stock boxes, one above the other, in place of the usual ten-frame brood chamber, reverting to the latter during the actual honey flow only.

In a prescient note to American beekeepersxxv, Ellis also noted:

While a brood-chamber can not be too large before the honey flow, this virtue becomes a defect if persisted in after the section supers are on…

As a means to this end, the Atkinson dual-queen system is attracting some attention here. On this principle two queens are wintered under one roof, each in her own six-frame brood box and by the addition of other similar boxes in spring the respective brood chambers can be expanded to any size required. Finally, both lots are combined with one queen on ten standard-sized brood-combs, when the days come for honey-gathering.

To conclude the Ellis-Medicus two-queen hive system and the Atkinson scheme, the latter an adaptation of the original Wells doubled hive and Ferris’s divided brood chamber, all employed an extra queen. The chief attribute of every scheme was their building hives to strengths way beyond the laying capacity of any single queen.

Where to next?

Both Wells and Alexander operated their hives with two queens right outside their back doors but under vastly different conditions. Medicus and Ellis, Atkinson and Ferris, employing standard hive bodies devised schemes for using two queens to build exceptionally powerful colonies in their home apiaries, but migrated their bees, not hives with two queens, to the honey flow. Collectively these disparate operators put honey gathering on steroids.

We think there are many salient take home messages for the average punter content to run a few normal single queen hives in their back yard:

- consider splitting your hives in mid spring with a clear view to reuniting them at the beginning of the main honey flow when the risk of swarming is over;

- consider requeening your hives in autumn and to strap pairs of hives together to share a little warmth over winter3; and

- consider strategies of building strong colonies very early to better enable them to pollinate your fruit trees and vegetables.

………………..

3The recent emergence of highly insulated high density polystyrene hives confers the advantages of better thermal regulation of overwintered hives achieved by the likes of Ferris and Atkinson.

………………..

And of course, thanks to Medicus, we have the first ever reliable two-queen hive. An upcoming series will outline the development of more modern and exceptionally efficient two-queen hives.

iButler, C.G. (1954). The method and importance of the recognition by a colony of honeybees (A. mellilera) of the presence of its queen. Transactions of the Royal Entomological Society of London 105(2):11-29. https://doi:10.1111/j.1365-2311.1954.tb00773.x

Butler, C.G. (1957). The process of queen supersedure in colonies of honeybees (Apis mellifera Linn.) Insectes Sociaux 4(3): 211-223. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF02222154

Butler, C.G. (1959). Queen substance. Bee World 40(11):269-275. http://transcontinental/doi/abs/10.1080/0005772X.1959.11096745

Butler, C. (1974). The World of the Honeybee. Collins New Naturalist, London.

iiSimpson, J. (1957). Observations on colonies of honey-bees subjected to treatments designed to induce swarming. Proceedings of the Royal Entomological Society of London Series A 32(10/12):185. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-3032.1957.tb00369.x

Simpson, J. (1958). The problem of swarming in beekeeping practice. Bee World 39(8):193-202. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0005772X.1958.11095063?journalCode=tbee20

Simpson, J. (1962). Work at Rothamsted on honeybee swarming. Rothamsted Experimental Station Report pp. 254-259. This report synthesises a wide range of observational and experimental reports on the whole gamut of swarming causes and behaviours, expanding a great deal on Huber’s account of swarming – includes a rich list of references to experiments he conducted and that are not found in most searches. http://www.era.rothamsted.ac.uk/eradoc/OCR/ResReport1962-254-259

Simpson, J. and Riedel, L.B.M. (1963). The factor that causes swarming in honey-bee colonies in small hives. Journal of Apicultural Research 2:50-54. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00218839.1963.11100056

Simpson, J., Riedel, I.B.M., and Inge, B.M. (1964). The emergence of swarms from Apis mellifera colonies. Behaviour 23:140–148. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4533084?seq=1

iiiSeeley, T.D. (2019). The lives of bees: The untold storey of the honey bee in the wild. Princeton University Press, Princeton and Oxford.

ivEllis, J.M. (1908a). Management at the heather: Wanted better methods and results. The British Bee Journal and Bee-keepers’ Adviser 36(1379):475-476. https://ia800202.us.archive.org/10/items/britishbeejourna1908lond/britishbeejourna1908lond.pdf

Medicus (1908). loc.cit.

Ellis, J.M. (1908b). Management at the heather. The British Bee Journal and Bee-keepers’ Adviser 36(1384):522-523.

vHall, C.A. (1907). Introducing queens: A modification of the Alexander method. Gleanings in Bee Culture 35(23):1592. (with a response from E.W. Alexander) https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.31951d00953180r;view=1up;seq=930

The National Bee Keepers’ Convention at Harrisburg, October 29-30 (1907). Gleanings in Bee Culture 35(23):1430-1432. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.31951d00953180r&view=1up&seq=830

Hand, J.E. (1907). The plural queen system: No problem to introduce a number of queens to bees, but difficult to introduce them to each other. Gleanings in Bee Culture 35(21):1385-1386. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.31951d00953180r;view=1up;seq=813

Hand, J.E. (1908a). The plural-queen system: Why is it more practicable with a division board-chamber than with an ordinary full-depth hive. Gleanings in Bee Culture 36(1):35-36. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b3458202;view=1up;seq=49

Hand, J.E. (1908b). The two-queen system: This plan makes it possible to keep the brood chamber packed with brood during the flow: Forcing honey into the supers: Wintering two queens in one hive not desirable. Gleanings in Bee Culture 36(3):155-156. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b3458202;view=1up;seq=167

Bussy, E. (1908). The plural queen system. A series of interesting experiments: Clipping the queen’s stings so they can’t kill eachother: Do the bees take a hand in royal combat? Gleanings in Bee Culture 36(3):156-157. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b3458202;view=1up;seq=168

Gray, J. (1908). The plural-queen system: How an English expert looks at the question;: advantages and disadvantages. Gleanings in Bee Culture 36(3):157. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b3458202;view=1up;seq=169

Hand, J.E. (1908c). The dual and plural queen systems: Conditions under which the may be used: Review of the whole question. Gleanings in Bee Culture 36(8):507-508.

viMedicus (1910). A two-queen system: Some remarks on its adaptability for a heather district. The British Bee Journal and Bee-keepers’ Adviser 38(1442-1444):55-56; 64-66; 75-77. https://ia800301.us.archive.org/1/items/britishbeejourna1910lond/britishbeejourna1910lond.pdf

Joice, G.W. (1911). Wintering a surplus of queens in one colony. The plan a success. Gleanings in Bee Culture 49(7):221.

Joice, G.W. (1911). More about wintering a surplus of queens in one colony: It is worth a trial. Gleanings in Bee Culture 49(14):436-437.

viiCruadh (1907). Plurality of queens: Another plan for introduction: Two or more queens to a colony. Gleanings in Bee Culture 35(23):1592-1593. https://archive.org/details/CAT93976214427/page/1594/mode/2up/search/Cruadh?q=Cruadh

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uma.ark:/13960/t7fr05w6z&view=image&seq=1608

Sherrod, J. (1907). The plural-queen system: More honey than from the one-queen system. Gleanings in Bee Culture 35(23):1593-1594. https://ia800702.us.archive.org/34/items/gleaningsinbeecu20medi/gleaningsinbeecu20medi.pdf

viiiDemaree, G. (1892). How to prevent swarming. American Bee Journal 29(17):545-546. https://ia802902.us.archive.org/21/items/americanbeejourn2992hami/americanbeejourn2992hami.pdf

ixFrost, R. (1916). The road not taken. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44272/the-road-not-taken

xFerris, A.K. (1906a). The hive adapted to the two-queen system: Reasons why ten-frame hive is unsuitable. Gleanings in Bee Culture 34(9):586-587. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.a0003415858&view=1up&seq=346 https://ia800902.us.archive.org/3/items/gleaningsinbeecu34medi/gleaningsinbeecu34medi.pdf

Ferris, A.K. (1906b). Comb honey by the two-queen system: Strong colonies for comb and weak ones for extracted honey: The advantage of a dual in each hive. Gleanings in Bee Culture 34(12):803-804. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.a0003415858&view=1up&seq=489

Ferris, A.K. (1906c). The Ferris system of producing comb honey and swarm control: A cheaper comb-honey device. Gleanings in Bee Culture 34(18):1184. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.31951d00953179c&view=1up&seq=698

xiSladen, FWL (1918). Intensive beekeeping. Trial of an intensive system of beekeeping. Canadian Horticulturist and Beekeeper. in Fowles, I. (December 1918). The best from others. Gleanings in Bee Culture 46:742.Sladen, FWL (1919). Combs from other hives: Trial of a system of keeping two queens in a hive. The British Bee Journal and Bee-keepers’ Adviser 47:281-282. Reprinted from Sladen, FWL (Feb 1919). Agricultural Gazette of Canada 6(2):130-134.

Sladen, FW (1919). Intensive beekeeping. American Bee Journal 59(4):118-119. https://ia800907.us.archive.org/21/items/americanbeejourn5859hami/americanbeejourn5859hami.pdf

Miller, A.C. (1919). Twin hives and others. American Bee Journal 58():274-275. https://ia800907.us.archive.org/21/items/americanbeejourn5859hami/americanbeejourn5859hami.pdf

xiiBritish Bee-Keepers’ Association Quarterly Converzatione (Thursday 7 April 1892). Mr Wells new method of working bees. The British Bee Journal and Beekeepers Record and Adviser 20(511):126, 132-133. https://ia802508.us.archive.org/29/items/britishbeejourna1892lond/britishbeejourna1892lond.pdf

xiiiSladen, FWL (1920). The Sladen two-queen system. American Bee Journal 60(3):84-86. https://ia802702.us.archive.org/19/items/americanbeejourn6061hami/americanbeejourn6061hami.pdf

Sladen (1921). Wintering two queens in one hive. American Bee Journal 60(9):348-349. https://ia802702.us.archive.org/19/items/americanbeejourn6061hami/americanbeejourn6061hami.pdf

xivAtkinson, M. (1921a). Dual-queen work—the double-six system. The British Bee Journal and Bee-keepers’ Adviser 49:501-502.

Atkinson, M. (1921b). Dual-queen work—the double-six system. The British Bee Journal and Bee-keepers’ Adviser 49:537.

Morris, C.S. (1920). Wintering two queens in one hive. The British Bee Journal and Bee keepers’ Adviser 48:27.

xvEllis (1922a) and (1922b). loc.cit.

xviAdvertisements for Atkinson queens and gear. (1921). The British Bee Journal and Bee-keepers’ Adviser 49:435.

xviiAtkinson, M. (1922). Advertisement for 1920 Cambridge Lecture notes. The British Bee Journal and Bee-keepers’ Adviser 50:49.

xviiiEllis (1922a). loc. cit.

xixAtkinson, M. (1921c). Foreign bees and the incidence of disease. The British Bee Journal and Bee-keepers’ Adviser 49:429-430.

xxAtkinson, M. (1920). Queens and tiered chamber bee spaces. The British Bee Journal and Bee keepers’ Adviser 48:280-282.

xxiEllis (1922b). loc. cit.

xxiiEllis, J.M. (1921e). Notes from Gretna Green. The British Bee Journal and Bee-keepers’ Adviser 49:549.

xxiiiEllis, J.M. (1922a). Notes from Gretna Green. The British Bee Journal and Bee-keepers’ Adviser 50:105. https://ia800202.us.archive.org/9/items/britishbeejourna1922lond/britishbeejourna1922lond.pdf

Ellis, J.M. (1922b). Notes from Gretna Green: Safe wintering. The British Bee Journal and Bee-keepers’ Adviser 50:547.

xxivEllis (1921c) loc. cit.

xxvEllis, JW (1923). Large hives for comb honey. Gleanings in Bee Culture 51(12):811. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b4243687&view=1up&seq=62ir

Be the first to comment