Bee Buzz Box

A Simple Swarm Control Guide

August-September 2018 Part I

Alan Wade

Never let old beekeepers get together! Like seasoned fishermen, they’ll spin you some tall yarn about the bumper honey crops they got before chalkbrood, small hive beetle or American Foul Brood came along. Them were the Halcyon Days.

Well anyway, there are a few well known practical ploys I and many others in the club practice to stop bees swarming.

Swarming or Supersedure?

Seeing queen cells in a hive sets most beekeepers off. But don’t assume your hive is about to swarm though that’s pretty likely. Let’s be clear. In the normal course of events there are a couple of reasons why bees need to raise queens . When you do something silly like squish a queen, the bees simply set to and raise a newbie. But there are two less tangible reasons why the bees need to replace their reigning queen.

Firstly to survive a colony must replace its queen now and then. Like any mum, the queen grows old and she needs to rely on a daughter to keep the family name going. An old queen allows her robots (aka almost sterile female workers) to raise a few daughters and one of them takes over the colony. Unlike children who get kicked out of home, this daughter knocks off her rivals as there is only room for one. Remember that beekeeping course: one hive, one queen. From the colony (or super-organism) perspective this replacement is non-reproductive in the sense that it’s the colony, not the queen or drones or workers, that must survive. We call this supersedure.

Supersedure usually goes unnoticed but seeing supersedure cells is often mistaken as a portent of swarming.

So before you reach for the hive tool to remove those cells carefully put it aside or mark the top bar and examine other brood frames. Count them and if there are no more than four or five cells (often just one or two) located in the centre of the brood nest then supersedure not swarming is taking place. Leave a few good lookers and put the lid back on your hive.

It will take several weeks for the new queen to take and several more for your hive to kick along. Quite often the old queen will limp along and even lay alongside her daughter. That’s why, when we requeen, we always inspect other brood frames once we’ve found the queen we want to replace. We’ve found half a dozen colonies with two queens in the club apiary and that’s saved a few failed introductions.

With supersedure, the bees are telling you they need a new queen and your knocking off their replacement risks making the colony queenless. At the very best, it will put them them back a couple of weeks while they try again.

Swarming is quite different. If you find lots of cells, and they are mainly hanging on the bottom of combs, then you are about to lose half or more of the productive capacity of your bees. The colony is about to reproduce itself (swarm). All that is happening is the colony spilts into two (and occasionally more) colonies. If you are curious and want to know more about the process read the famous Farmers Bulletin article by Demuth (Readings).

Remarkably, if your colony swarms it, too, ends up with a daughter queen. It’s just that the old queen takes off with your bees and your queen to found a new colony elsewhere. You are left wondering if it might have been otherwise. These days, once you have some inkling that your bees might be preparing to swarm you can adopt any one of a few sure fire control measures.

Swarming – a Reality Check

Bees have never had any choice. They’ve always swarmed, and then many many times over their long period of evolution. That started about 40 million years ago from the first recording of Apis in fossil amber. Go back further to around 90 million years when the common progenitor of the honey, stingless, bumble and orchid bees first assembled for their mutual benefit and started sharing tasks such as defending the patch and ceding laying responsibility to mainly one queen and the one drone she mated with.

Social bees must replace some colonies to make up for any that are lost, those that die of natural causes such as disease and starvation. Of course there are other causes of loss amongst honey bees, predation by bears and honey hunters and now attack by small hive beetle to name but a few.

Bees swarm naturally, mainly in spring but only under good conditions. This they mostly do early in the season. This gives the swarm, and the parent colony, plenty of time to settle, build up in numbers, build stores and survive another winter.

But you have a choice. You can let your bees swarm – and lose that good queen and a hell of a lot of honey – or you can sensibly intervene. Instead of relying on cutting out swarm cells – miss one and they will swarm – why not adopt very simple swarm control practices once your bees are quite strong and well before they actually head off to the never never. Removing queen cells only buys you 2-3 weeks reprieve when, if you don’t get back to them, the bees will swarm anyway.

The club has lost one swarm over the past two years. Think about it. Most colonies, even with queens replaced annually, will swarm every year so it makes sense to understand the basics and take action.

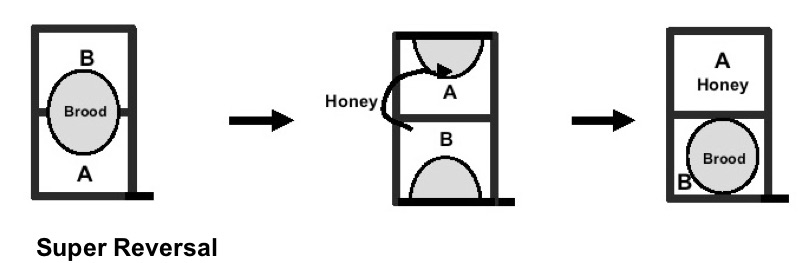

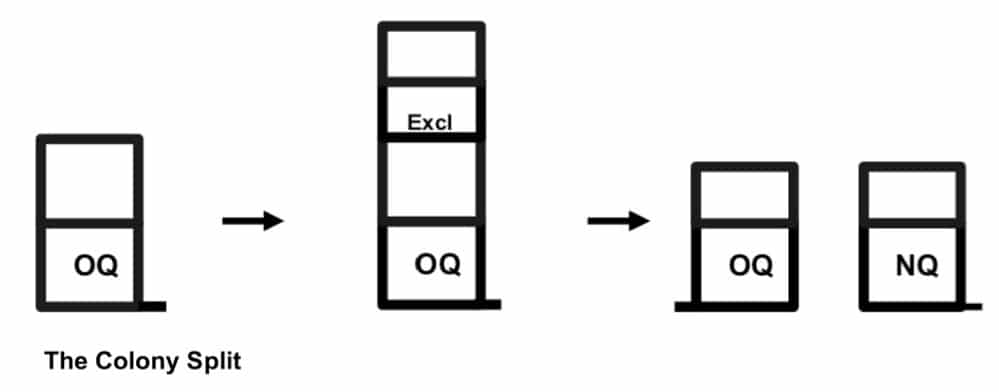

There is Super Reversal, not a dinkum swarm control measure but which, in practice, will delay swarming. Anyway it’s a pretty handy management tool for hurrying your bees along. Then there is The Colony Split. It works like a charm but it requires extra gear and you have to be aware that it will take many weeks for the colonies – especially the queenless part – to fully recover and be ready for the main honey flow. Finally there is the much maligned and often misunderstood Demaree Plan. It works a treat and has the great advantage of keeping your bees together under the one lid.

Super Reversal

There are many ways to impede the swarming impulse and one is Super Reversal. A couple of years back – in fact on the first day of spring – a quick whip around the club apiary showed that, in all but one Langstroth, every one had eaten their way through all their lower brood box stores. The brood and queen had moved upstairs. The beggars were chewing into remaining stores and would soon have starved. They weren’t about to swarm but we did swap the boxes around as shown – and then fed them heavily – to give them a good start. Soon enough however it was time to reverse the boxes again, or at least consolidate as much brood as possible in the lower brood chamber.

By reversing supers, the queen moves down with the brood while the bees move honey up and to fill up the combs under the lid as any extra brood in the upper box emerges. This simulates a light honey flow and stimulates the queen to lay. Hence more pheromones are moved around and this makes the colony less inclined to swarm.

Take care. Don’t reverse supers if the nights are cold as you may be spitting the brood nest and there is a severe risk of losing brood to chilling.

The Colony Split

When we approached Jim Calokerinos to revisit his no-swarm solution to beekeeping this cunning old beekeeper had done his OT trick. Jim had evaporated to Greece (Over There) to avoid Canberra’s winter chills.

Jim splits his hives every spring once they get up real muscle. Not surprisingly, if you suddenly halve the work force and halve the amount of brood they have, they don’t swarm. It’s as though you’ve done the swarming for them and hey they stay at home to regain honey gathering strength, but not in the neighbours brick wall. More surprisingly, Jim simply reunites the colonies at the beginning of the honey flow and harvests the bumper honey crop as fast as it comes in.

Jim is never fooled by the old adage of ‘more bee hives equals more honey’. He knows full-well that too many colonies means too much work and that swarming will rob you of the honey you might have had. By the time the main honey flow commences, normally November, bees have largely given up their swarming intent and returned to their serious honey gathering pursuit. Jim simply pastes his colonies back together to form giant colonies in order brings home the bacon, err, sorry honey.

Narrabundah Lane Apiary September 2015: L to R

Herb Waldie, John Howe, Adrain Wright,

Jim Calokerinos and Dick Johnston

Let’s say we start with a colony that comes out of winter well with good stores and plenty of bees. It builds quickly so we reverse supers, pop an excluder on and put on another full depth box or a couple of half depth boxes so the bees have room to raise brood and also to store honey. Putting more gear on works but only for a while. As soon as the bees are very strong, or actually begin building swarm cells, we split the whole caboodle into two colonies so that one retains the old queen (OQ) and the other has no queen (NQ). Pretty quickly the queenless unit raises its own new queen but it can take five or so weeks for the this queen to emerge and to have her own worker brood emerging. So you can speed that process up by simply queening the queenless part or by using a swarm or supersedure cell from another colony.

We have always been impressed by Jim’s story. He said all of that in just a few words over a cuppa one evening after a club meeting: ‘I can’t see the problem. I split my bees. I don’t have swarming problems’. That has not always been the case as we have all had to learn the hard way, but it does work for all us old timers.

Demaree Plan (next month)

When we finally caught up with Jim again, we drew admissions that he did few other necessary things. Like us he requeens regularly and does regular disease checks. In the sequel we will explore the widely misunderstood but very remarkable Demaree Plan. It was invented way back in the early 1890’s. It is quite different to hive splitting and, as we shall see, requires no gear other than a single queen excluder and maybe an extra super. We will conclude our simple swarm control guide with a brief recommendation to requeen regularly, a great practice for not only reducing swarming incidence but for making you the owner of strong healthy bees.

Readings

Demuth, G.S. (1921). Swarm control. Farmers Bulletin 1198:1-45. United States Department of Agriculture (see page 5). https://ia601401.us.archive.org/32/items/CAT87202908/farmbul1198.pdf

Wade, A. (2017). Swarming in honey bees, parts III and IV. The Australasian Beekeeper 32-36; 119(4): 48-51; 119(5): 40-42.

Be the first to comment