Alan Wade

Hives with two queens

In Part I we explored the ‘The one colony – One queen principle’, the universal condition of the honey bee colony. That two or more queens might be introduced to a honey bee colony, or indeed even be naturally present, is a consequence of the need for honey bees to replace their queens periodically. Under the unstable ‘queen changeover’ period, a second queen (during supersedure) or even a number of virgin queens (during swarming preparations) can be and are often present.

It was not until the 1980’s that it was recognised that two queens could be introduced by an apiarist under conditions more or less identical to those under which a single queen is replaced (see Part I). The end result of this finding was the development of the consolidated (double-chamber) brood nest (CBN) containing two queens. Such a colony is quite stable for the duration of summer honey flows and has proved to be a formidable honey gathering machine.

There is a subtle difference between the organisation of a two-queen and that of a single-queen colony: in a single-queen colony all bees can have access to all parts of the hive; in the two-queen colony the worker bees and drones can mix freely, but the queens must, or just happen, to be kept apart. The two-queen colony can be operated with discrete brood nests – this was discovered in the 1930s – or in the more recently discovered CBN single brood nest configuration championed by Hogg.

So it seems as though operating a two-queen colony should now be straightforward and should, in principle, be no more difficult than running a single-queen colony. In practice, however, running two-queen hives is more like herding cats: it’s never obvious when and how to start herding and, at the same time, be certain that you can keep the tom cats apart. What this means is that, unless you have a modicum of beekeeping skills, setting up and operating hives with two queens might best not be for you. Robert Banker of The Hive and Honeybee fame ran 1500 two-queen hives (and many backup splits and nucs) using the older separate brood nest model, but then he was no ordinary beekeeper. We will return to the exigencies of operating two-queen hives in Part III.

Not all beekeepers are fooled by bees

Insects do not sense the world the way we or other vertebrates do. Honey bees, insects with advanced communication acumen, operate in a flickering world devoid of colour discrimination (they see changes in intensity of blue, navigate by polarised light from the sun (Apis dorsata can also use the moonlight to fly at night even though the moon does not influence their navigation) and judge distance by object count using green colour receptors (https://biology.anu.edu.au/research/do-bees-distinguish-colours). In the dark interior of the hive they respond to vibrational signals and a bevy of pheromones, a weird mix of chemicals transmitted by trophallaxis (food exchange) and by volatile terpenes that together send myriad signals. These ‘vibes and smells’ solicit behaviours such as defence, recruitment of foragers and comb builders, regulate drone comb building and numbers of drones and control queen cell building. Enter the factors that determine acceptance of a queen, conversely the rejection of a potential usurper, and it’s no wonder our second guessing what bees ‘think about their queen’ is more folk law than objective reality.

Scientists such as John Hogg have unravelled many of the mysteries of honey bee behaviour. This researcher asked a question very pertinent to queen and worker bee interaction: ‘What factors influence acceptance and retention of a queen in a honey bee colony?’ He, for one, was not entirely fooled by the bees. He elucidated the factors that control the acceptance of not just one, but two or more queens. He discovered that, under controlled conditions, there was little difference in their willingness to accept one or many queens. It would seem that he had realised the apiarist’s dream, how to fully control queen bee introduction:

- For we are the music makers,

And we are the dreamers of dreams,

Wandering by lone sea-breakers,

And sitting by desolate stream;—

World-losers and world-forsakes,

On whom the pale moon gleams:

Yet we are the movers and shakers

Of the world for ever, it seems.

Arthur O’Shaughnessy “Ode” in Music in Moonlight 1874

Single-queen colony requeening

Bees will only accept a ‘new mum’ if they get a signal that they need a replacement. It appears they need to be deprived of the queen mandibular pheromones and likely some others, those broadcast by a healthy colony queen and distributed by her attendants, to either raise a new queen themselves – a task they have perfected over almost 90 million years – or to remove an intruder. You replicate the queenless condition by simply taking the old queen away and then offering the colony a new one.

The mailing cage method

In this approach you take out the old queen, allow some hours, ideally a day or two, and put the cage with the new queen into the brood nest. If you haven’t used an excluder and the brood is spread through several supers, consider putting one in a week or so before the new queen is due to arrive. Then you will only have to search one box, the one with eggs, to locate the old queen.

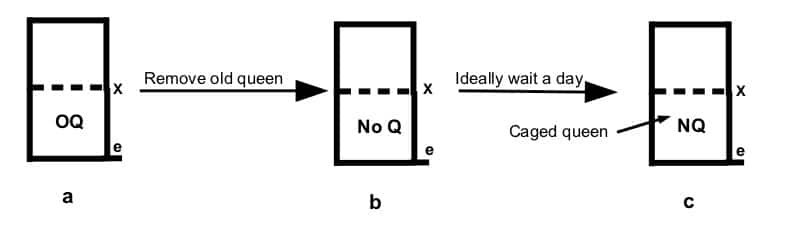

Figure 1 Requeening using the cage method: e = entrance; x = excluder. The old queen (OQ) is first isolated (a); that queen is then removed (no Q) noting occasionally that there are two to remove (b); the colony is left queenless for at least several hours and the mailing cage queen with the new queen (NQ), candy pointing upwards, is placed on top of, or into, the brood nest (c).

I find it useful to mark the location of the frame with the cage on the top bar to make it easier to check that she has been released at the subsequent inspection. Leave the colony undisturbed for at least a week, but no more than three weeks, before checking she has taken and is laying. By intervening too early, you may upset the delicate process of queen acceptance and lose the new queen. By leaving the inspection for too long you cannot be quite certain the colony has not rejected the introduced queen and gone on to raise their own emergency or supersedure queen.

That the cage introduction method works well means that many beekeepers never venture to ask why it is so successful. Once the old queen is removed, the pheromone signal fairly quickly disappears, the bees lose some of their cohesiveness and set about raising one or several queens. They reprogram very young larvae, originally destined to become workers, and feed them lavishly.

Stray emergency queen cells are easy to distinguish from supersedure and swarm cells. Emergency cells originate from within the comb matrix. Their presence is first evident from the flaring of worker cells at the commencement of queen building. Swarm and supersedure cells are purpose built and adhere to, rather than originate in, the comb surface or the edge of the frame so their attachment makes it easy to distinguish them from emergency cells. However this is an aside: we need to focus on successful means of queen introduction.

Problems with the cage method of introduction arise if the queen is released too quickly, you miss a swarm or supersedure cell present when you introduce the queen, or if you miss roaming virgin queens present for as long as several weeks especially when a colony repeatedly swarms. When requeening always check all brood combs, the most likely place to find queens, for the presence of a second queen. Also be extremely wary of trying to requeen a colony with laying workers. In that instance it is better to shake out the mainly old bees well away from other hives and start the new queen in a nuc made up from a strong colony.

Is there a way of telling whether or not an old or stray queen is present when you come to requeen? Most beekeepers have been guilty of assuming that if they can’t find a queen then one is not present. Even if there is no brood, introducing a queen without a very simple check of all brood frames invites failure. If you are still uncertain about the queen (more correctly gyne) status of your hive, simply take a frame with eggs and young brood from a healthy colony, mark the frame and place it into the centre of the hive you believe is queenless. If indeed there is no queen then that marked frame will have emergency queen cells easily recognisable after 1-2 days. You can then safely requeen the colony having been assured that it is truly queenless. Otherwise keep searching for the old queen – she may or may not be laying.

Nuc method

A more successful means of requeening is to queen a small colony (a nucleus colony better known by its epithet nuc) and use that to requeen a large colony. That’s not practical in a large commercial apiary, but having nucs available to requeen a failing colony or using them to create new nucs is widely practiced.

Choose a couple of good brood combs with stores and covered with bees, ideally containing some sealed brood and shake in a couple of extra frames of bees (without the queen) to allow for the fact that field bees will drift back the the parent hive. Leave it queenless for a day, introduce the cage and establish the new queen over a period of at least three weeks.

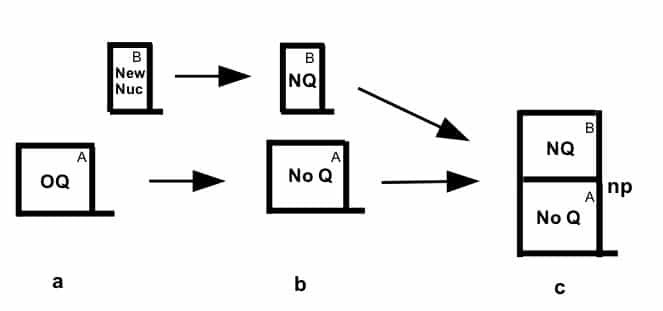

By the end of this time the new queen will have her own brood in all stages and her workers will fully acquire her chemical signature and will have the same status as the colony to be requeened. Then, with the benefit of two queens laying and no break in the brood cycle, remove the old queen and paper on the nucleus (Figure 2).

Always put the newly-queened nuc on top.

Figure 2 Requeening using a nuc: OQ = old queen, NQ = new queen; np = newspaper. Remove (OQ) from colony (a) leaving colony in a queenless (No Q) state (b) for a day or two and paper on nuc introduced to a full sized super (c) containing the new queen (NQ).

The only improvement to this method is to make up the new nuc with only emerging sealed brood and bees (minus the old queen) from the brood nest, mainly young bees that will accept any queen. To remove older bees, give brood frames a gentle shake – only young, newly emerged bees will stay on the frame as you can see from their ‘fluffy’ appearance. Nucs with newly emerged bees will better accept queens than will nucs made up simply by breaking up or removing frames from a hive.

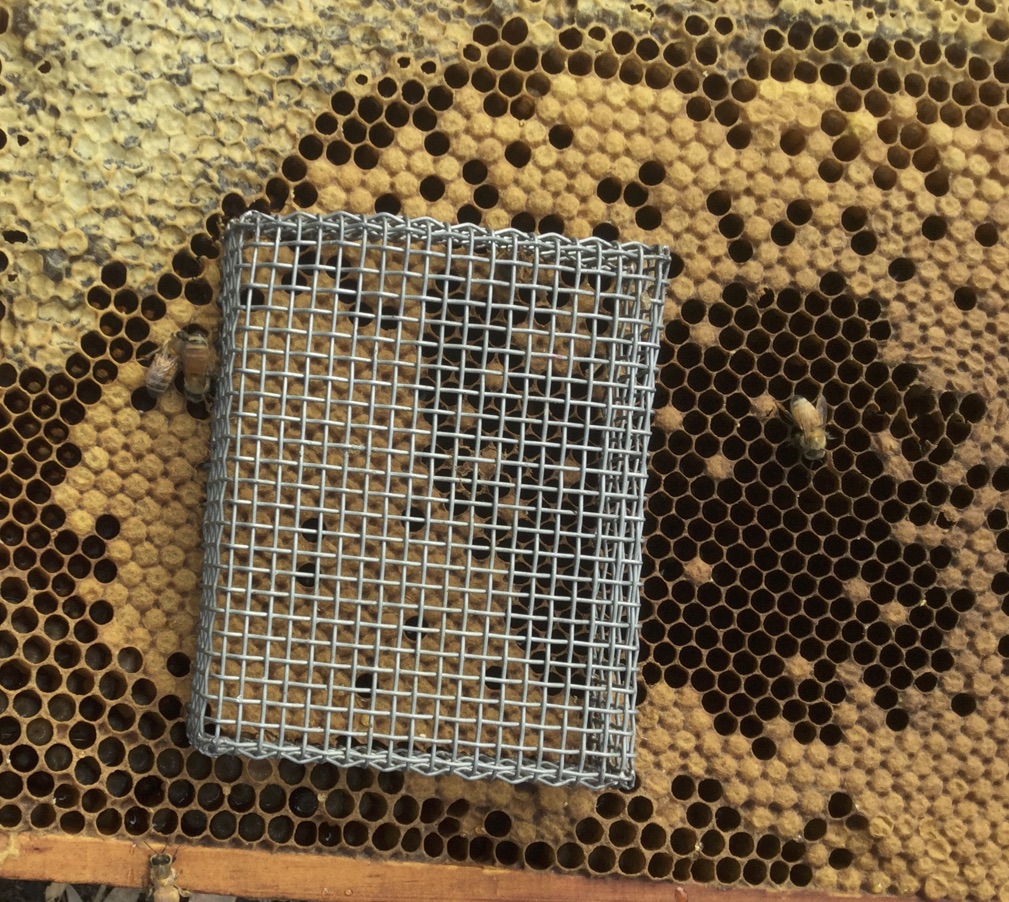

There is another trick that requires a little more effort and skill. Instead of introducing the mailing cage directly you can remove her from the mailing cage (under a net to avoid risk of escape), mark her and carefully imprison her (without the old escorts) under a wire cage pressed into the face of a comb with emerging brood. Return 3-4 days later and, with minimal smoke and disturbance, remove the cage, check for the presence of eggs and watch the queen walk away. Gently reassemble the nuc and leave it alone till the new queen is well established. Again, allow the nuc to establish itself before attempting to requeen the parent hive.

Woven wire queen cage (100 x 80 x 25 mm): Open (left); Pushed into emerging brood comb (right)

Other methods

Alternatively a nuc can be employed to accept well formed supersedure cells you happen to find in colonies that are otherwise performing well. Using queen cells from strong colonies, those able to optimally raise queens, is a good option as is buying queen cells from a breeder. But, before you get your hopes up, they must be carefully harvested and wont survive mailing.

Then there are some special techniques for requeening large honey bee colonies replicating supersedure, but you must know what you are doing. Such techniques are inimical to two-queen hive operation.

If you return to Part I you will see that some other simple tricks can enhance queen acceptance. Feed your bees liberally with sugar water before introducing queens and avoiding ‘grumpy’ conditions, really poor weather, dawn or dusk, or when bees are robbing and chasing you around the yard.

Two-queen colony queening

As we have seen the conditions for the successful establishment of a two-queen colony are essentially the same as those for simple single-queen hive requeening. More care is needed as any mistake will result in either:

- only one queen being accepted; or after a short period

- one queen being superseded due to unequal queen or brood status; or

- the colony swarming taking one of the new queens with it.

John Hogg identified three pathways to establish a consolidated brood nest two-queen colony:

(a) Simultaneous direct introduction of two laying queens, virgin queens or queen cells

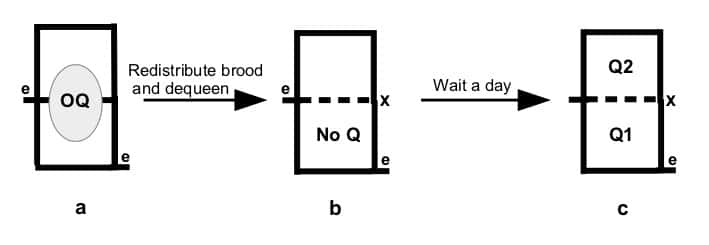

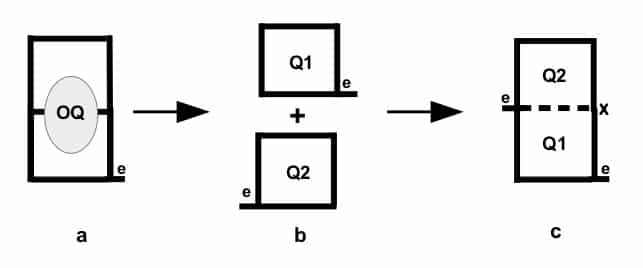

This requires that both queens be in an very similar condition (e.g. both mated caged queens or two nucs with laying queens) and that each brood nest be closely matched for condition. Further bees in each unit must be trained to use their own entrance so that, once united, the bees do not find the need to use each other’s brood chamber’s entrance. This is best illustrated by way of a simple example (Figure 3). Figure 3 Direct double queening starting with a double brood chamber conditioned to employ two entrances: OQ = old queen, Q1 and Q2 = new queens, e = excluder; x = excluder. The sequence involves splitting the double brood chamber (a); removing the old queen and redistributing brood to equalise brood nests (b); and introducing new queens both at exactly the same time (c). Newspaper can be employed but because both brood chambers are in the same condition and bees all come from the same colony, it is not really needed.

Figure 3 Direct double queening starting with a double brood chamber conditioned to employ two entrances: OQ = old queen, Q1 and Q2 = new queens, e = excluder; x = excluder. The sequence involves splitting the double brood chamber (a); removing the old queen and redistributing brood to equalise brood nests (b); and introducing new queens both at exactly the same time (c). Newspaper can be employed but because both brood chambers are in the same condition and bees all come from the same colony, it is not really needed.

(b) Uniting queenright colonies

This method is probably the least risky and most assured of success, one we visited in Part I. Each unit is first acclimatised for flight entrance condition where the units are first stacked (separated by a nuc board or double screen) or placed alongside each other. In this example (Figure 4) a strong colony is split in mid spring and the new and old queen (or two new queens) are established as separate colonies (b). Once well established (allow at least three weeks) simply paper the two colonies together (c) always locating any older queen below. Single colonies (or nucs) from an out-apiary can be entrance trained for a few days and then directly united avoiding step (a).

Figure 4 Uniting two queen right colonies. OQ = old queen; Q1 old or new queen; Q2 new queen – ideally of the same provenance as Q1; e = entrance; x = excluder: Here two new colonies are established from an overwintered double colony] (a), allowed to develop for several weeks (b) and then united using newspaper and excluder to form a two-queen colony (c).

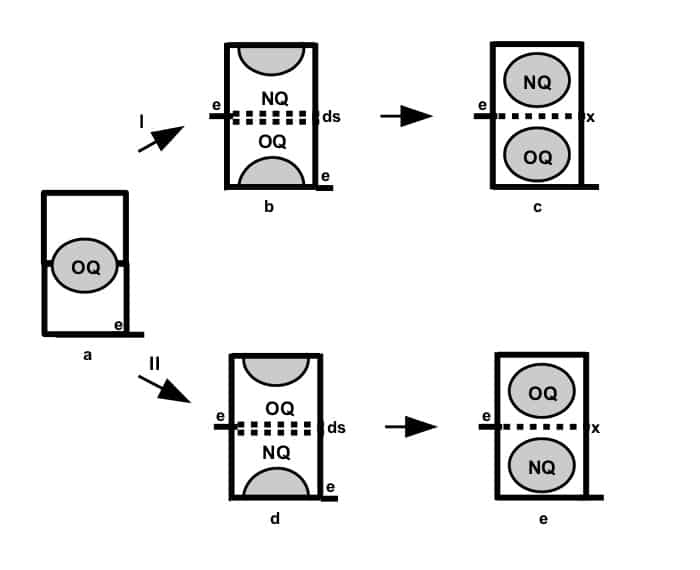

A simple variant used by Hogg in early experiments setting up CBNs is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5 Two step process for uniting two queenright colonies: ds = double screen; x = excluder; e = entrance. The process starts with a strong double brood chamber hive with an overwintered old queen (OQ) (a). In this setup, two new colonies are established in situ (b or d). Uniting these colonies (c or e) must be delayed till the both colonies (above and below the double screen) are well established. Note the double screen made of woven wire mesh allows free circulation of air but is small enough to prevent movement of bees (~ 5 mm mesh).

The new queen (NQ) can be a mailing cage queen introduced to the queenless part of the split or an emergency queen can be raised by the bees as a walkaway split. The obvious advantage of introducing a laying queen is that the unit will immediately have a laying queen and the units can be united sooner (after about three weeks) than if a queen is raised by the split (5-6 weeks).

Pathway I

In this event (b and c) the upper unit with a good supply of sealed brood will benefit from rising warmth of the unit below and from emerging worker bees, both conducive to raising a new queen if one is not supplied. Progress of the introduction of the upper queen can be monitored by simply lifting the hive lid to check for establishment of the new queen (or cell) and presence of eggs. However, in the interim, there is some risk of the lower unit becoming too crowded and swarming, a condition that can only be alleviated by under-supering the double screen. This defeats the purpose of direct establishment of a consolidated brood nest.

Pathway II

In this setup (d and e) the lower super will take some time to establish so will be at reduced risk of swarming. However the upper unit can be supered without upsetting the future CBN brood nest arrangement.

(c) Sequential direct introduction of a second upper queen to an already queenright colony

At first sight this would seem to defy the fundamental principle ‘One colony – One queen principle’. Try to introduce a second queen to an already queenright colony and, in the normal course of events, the new queen will always be lost. However, if the upper colony is ‘conditioned’ to be in a semi-autonomous state, then a second queen will be accepted.

To achieve this state bees must be conditioned to use upper and lower entrances (a) and only sealed brood must be present in the upper brood chamber. Unsealed brood, all located in the lower brood nest, will attract nurse bees down through the excluder, but only as needed, while nurse bees tending the lower queen brood nest will not be not drawn upwards. Any emerging bees above the excluder will be receptive to the new queen (and migrate down through the excluder if surplus to needs) while field bees will continue to use their respective entrances. For a while, at least, the units above and below the excluder, though not isolated, operate semi-autonomously.

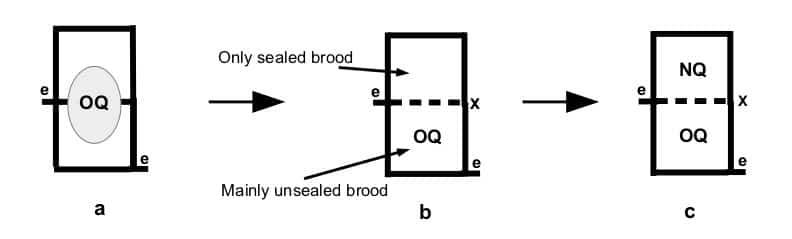

This arrangement is a little challenging to grasp but very simple in execution (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Sequential queen introduction of a second queen to an already queenright colony. OQ= old queen; NQ = new queen, e = entrance; x = excluder. Here the process commences with parent colony (a) with double brood nest and one queen; (b) reorganised so that only sealed brood remains above (b); a mated queen in the same laying state as that of the lower queen is introduced to the top brood chamber (c).

If a virgin or queen cell were instead introduced, it would not lay quickly enough to form a brood nest of equivalent status to that of the established queen in the lower brood chamber and so will be lost.

Perhaps the best evidence that this system works comes from the success of Demaree swarm control plan. There, separating nearly all the brood from the queen using an excluder, induces supersedure-like conditions in the queenless upper chamber containing nearly all the brood. In the Demaree plan, there is no queen in the upper super, so none is at risk, but supersedure cells are started signalling a queen-accepting (if temporary) condition. In sequential introduction we take advantage of this receptive condition in the queenless part of the brood nest, but no young brood is present.

The sequential introduction of a second queen is premised on the semi-autonomous starting condition of the upper brood nest and relies on the lower brood chamber bees not encroaching on the ‘personal space’ of the upper brood nest. The techniques is reminiscent of E.W. Alexander’s 1907 discovery that, with exceptional care, two or more queens can be established without an excluder, a long lost finding we touched on briefly in Part I. In concluding this series we will take a close look at the rather challenging endeavour to successfully operate two-queen hives, a task daunted by mountains of bees and, potentially, rivers of honey.

Readings

Alexander, E.W. (1907). A plurality of queens without perforated zinc. Gleanings in Bee Culture 35(23):1136-1138. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.31951d00953180r;view=1up;seq=

Hesbach, W. (February 2016). The horizontal two-queen system. Bee Culture online at http://www.beeculture.com/the-horizontal-two-queen-system/

Hesbach (2015). Two queens, one hive=lots of honey. Honey Bee Suite. https://honeybeesuite.com/two-queens-one-hivelots-of-honey/

Heuvel, B. (March 2013). Running two-queen colonies. http://www.beesource.com/forums/showthread.php?306234-Running-two-queen-colonies&p=1202508#post1202508

Nabors, R. (1 August 2016). Comparing two-queen colony management methods. American Bee Journal 156(8)-. Beekeeping topics http://americanbeejournal.com/comparing-two-queen-colony-management-methods/

Be the first to comment