“Special Bonus Issue”

Alan Wade, Frank Derwent and Agnes Koros

By now Canberra Region Beekeepers’ bees stirred, unseen, will be raising brood and tucking into their dwindling winter stores. So what might we do to maximise the chances of getting the best out of our buzzers and to prepare for the phrenetic start to the beekeeping season?

Having already made running repairs to gear and having long-ordered a few replacement queens, the best plans is to undertake that vital early season disease and stores check. There won’t be too many bees, so checking bees for their general condition by mid September can be quite straightforward. Try to pick a warm still day but don’t leave any hive open longer than needed. A good beekeeper will take notes on colony condition to provide a baseline for further action. And she or he will immediately take action to resolve any disease problem or stores shortfall.

Armed with a good mind map of the state of each of your hives there are really only two practical things you then need to do to take full advantage of honey flows.

Number 1 Build hives to full strength quickly to take capitalise on mid spring blossom and ground flora flowering – and occasionally an October Red Box (Eucalyptus polyanthemos) flow – and for all later usually box flows.

Number 2 Intervene to prevent swarming when the bees get ahead of themselves.

The practical reality is that building bees quickly (Number 1) will exacerbate the risk of swarming (Number 2). It’s a case of no good deed goes unpunished. However working with the bees rather than against their instincts to swarm, that is allowing them to build uninterrupted while at the same time intervening to prevent swarming, is the mark of a seasoned apiarist.

Number 1 – Building your bees

The best prospect for improving the lot for your bees is to avoid taking advice from bloggers who advocate having bees because they ‘add value to the environment’. Many are better characterised as wishful bee owners, not stewards of bees. Livestock needs good husbandry, in old parlance becoming the Good Shepherd, Psalm 23 for those who may not have been steeped in church attendance:

The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want.

He maketh me to lie down in green pastures: He leadeth me beside the still waters.

He restoreth my soul: he leadeth me in the paths of righteousness for His Name’s sake.

Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me; thy rod and thy staff they comfort me.

When it comes to adopting best beekeeping practice, ones instincts might be to delve into the lifelong findings of myriad bee heroes, people like Clayton Leon Farrar and Everett Franklin Phillips whom we shall call on. And we might add, why not consult the very best of a new generation of beekeepers, people like the folks at Australian Honeybee or Randy Oliver at scientificbeekeeping.com. Consulting these oracles is better than ‘going with the flow’, that is if you don’t want to swim against the tide and miss out on that decent honey flow.

Farrar has emerged as one of the greatest beekeepers of all time. He was the first person to correlate actual bee numbers with surplus honey gathered. A strong healthy colony will consume about 130 kg of honey and 30 kg of pollen each year, so what bees swarm with or predators and disease don’t take account of is what you can harvest. And a really powerful colony will collect more than 150 kg surplus of honey in a good year even in a backyard.

Farrari gathered records meticulously, factoring out district and inter-annual factors that change the maximum crop that can be gathered in any one year in any one locality. He produced clear-cut performance charts like this one – the outcomes are self-explanatory. He went on to pioneer and champion two-queen colonies, regular honey flow machines.

Farrar (1968)ii. Influence of colony populations on colony yields and production per bee. (Colony gain at each population level divided by the yield at 60,000 equals the percentage yield ——-; colony gain divided by its population equals the production factors per bee or relative production per unit number of bees.- – – – -)

What to do first up?

It is hard to know where to start or whom to believe when deciding what to do at that first spring visit to the apiary. However, we believe Farrar was not far off the mark when he observed:

The basic requirement for productive colony management in beekeeping are large food reserves of pollen and honey at all times and ample room for these food reserves, brood rearing, and the storage of surplus honey. Young productive queens from good stock are essential. The queen should be supported by a large population favorable to the time of the year.

The object is to build maximum colony populations for the nectar flow and maintain them throughout the season. The most populous colonies produce not only the most honey per colony but the most honey per bee. Brood rearing is the basis of colony development and the maintenance of maximum populations during the flow. It is dependent upon:

- the queen’s capacity to lay eggs;

- the supporting population’s ability to maintain favorable nest temperature and feed the brood;

- reserves of pollen and honey; and

- space in the proper position for expansion of the broodnest.

From here one might reasonable surmise that it would seem prudent:

- to have less swarm-prone young queens (<=18 months old in any hobby situation) capable of laying the maximum number of eggs;

- to keep a spare nuc or at least order a couple of queens if you have more than a few hives and promptly replace any under-performing queen;

- to have good stores and either a pollen flow or supplements to optimise nutrition;

- to provide space both within the broodnest, and above brood to draw comb and store and ripen honey;

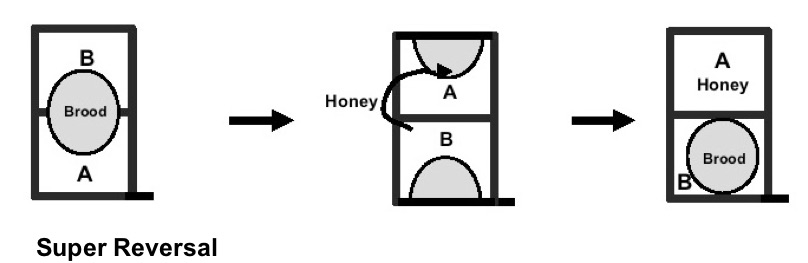

- to reverse brood supers (assuming you run double super broodnests) regularly to stimulate brood development and to delay swarming preparations;

- to make sure your bees are healthy at the outset; and

- to ensure your beehives are in full sun and out of the wind.

What next?

Again it’s not such a bad idea to see what practices apiarists of note have adopted or observed in the past. Take for example counsel that Everett Franklin Phillips gave in 1915iii:

The activities of bees vary during the seasons and no two localities present to the bees and their owners exactly the same environmental conditions, so that the successful beekeeper is one who has a knowledge of the activities of bees, whereby he can interpret what he sees in the hives from day to day, and who can mold the instincts of the bees to his convenience and profit.

François Huberiv, in his 1806 Letter IX to M. de Reaumur, was the first to establish many of the underlying facets of honey bee reproduction. For example he made the astute observation that:

In the course of spring and summer, the same hive may throw several swarms. The old queen is always at the head of the first colony; the others are conducted by young queens. Such is the fact which I shall now prove; and the peculiarities attending it shall be related.

One might even explore what the Polish apiarist Johann Dzierżońv – the Father of Beekeeping – found around 1882. His discovery of bee parthenogenesis and his homilies on what bees could teach us about moral rectitude are noteworthy:

Bee-keeping is, moreover, a source of moral improvement, which should not be overlooked. Whoever has once experienced the pleasure to be derived from the study of culture of bees will, I am convinced, spend every leisure hour in his apiary; and in doing so he will escape temptations to immoral and expensive amusements, and while contemplating the indefatigable industry, the cleanly and orderly habits, and the attachment of bees to their queen, he will be encouraged to follow their example; and even should circumstance not permit any material gain, his moral nature, at least, will be greatly improved.

Reading on, one might surmise that the tried and true techniques of maximising brood production – the hive engine – and intervening to prevent swarming and then to super strategically coming into the honey flow are practices that might be sensibly adopted. One takes positive action to make the bees ‘believe they have swarmed’ to keep them in population building mode. As we shall see swarming can be stopped in its tracks by colony splitting, transferring brood to weaker hives, or by ‘Demareeing’, all simple practices that can be adopted by any beekeeper who has opened a hive and will tell you they can distinguish a worker from a drone bee.

Once the season progresses, and bees have abandoned any tendency to swarm, one turns to reuniting bees – putting any split colonies (see below) back together – and to focus on honey super rotation and on honey removal. Strong bees on an average flow will build and fill comb quickly. If it is any indication, a strong colony will easily process 10 L of fed heavy sugar syrup within 48 hours so never underestimate the capacity of bees to literally work themselves to death.

A few asides

Firstly we have found there is a lot to be learnt a lot from ‘natural beekeeping practices’ such as nadiring (under supering in Warré and now obsolete skep practice) to mimic wild hive development in a tree hollow. In a tree hollow, bees build downwards during honey flow conditions so providing enough but not too much space below makes sense. The process is reversed as bees consume their stores faster than they can bring the bacon home, especially coming into spring. And at seasons’ end always remove all queen excluders so the queen is never stranded when there are ample stores upstairs.

Secondly timing is critical to all hive interventions but is something inexperienced beekeepers may not fully appreciate. Getting new queens in early, stimulating brood nest expansion by employing timely techniques such as brood spreading, strategic feeding and super reversal – while avoiding brood chilling – are all part of the apiarist’s armory for building bees.

Always take decisive action to prevent swarming, but don’t fall for the trap of relying on swarm cell removal as an effective means of control. Let’s be quite up front, the simplistic approach of swarm queen cell removal is necessarily short lived and shortsighted. Bees will continue to make preparations to swarm and, in less than a fortnight, half the bees will abscond. Anyway bees intent on swarming will literally stop harvesting and building comb while the queen will also stop laying as workers severely curtail her food supply.

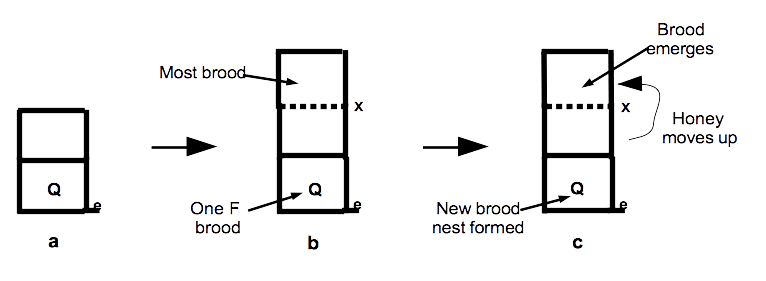

Reversing supers, often as early as first spring inspection where most bees and brood are often found in the upper super discourages, though is unlikely to prevent, swarming. The queen is encouraged to expand her brood nest as residual stores are moved up into the now upper super [A]. The process mimics a light honey flow, keeps the bees busy and encourages colony expansion.

Having made sure your bees have adequate honey and pollen at all times – a full frame of brood will consume a full comb of honey and emerge to cover three combs – watch out for the tank running on empty and for an explosion in the bee numbers. And of course you must have enough nursery space for the queen to max out on producing honey harvesters and having enough real estate to process nectar and store honey is a no brainer.

In spring, always assume the colony’s singular purpose is to make multiple attempts to swarm, their only sure fire way of surviving. And if you miss a queen cell when trying to thwart swarming by the queen cell removal strategy, they will actually swarm in a matter days if not hours. Not a practice that one should pander to. Let’s look at ways to limit if not entirely prevent swarming.

Swarming is not a new problem September

in the Rohan Hours c. 1430-1435.

Number 2 – Intervening to prevent swarmingvi

Not having enough real estate is a bit like trying to raise ten kids in a granny flat and trying to store the groceries on the back steps. Ever thought you could store that free bag of apples and the icecream only to find the larder was full and there was no room in the freezer? That’s the recipe for most of the family to leave home.

Requeening and providing space are time-tested measures to reduce the risk of swarming. But strong healthy bees with prolific queens, especially under good early season conditions, will often prepare to swarm anyway. We clearly recall talking to Warré champion Tim Malfroy (the club gets queens from his father Frank) in the spring of 2017: ‘No matter what we do bees are swarming everywhere this year’.

However, there are two oh-so-simple tricks to stop swarming and both replicate actual swarming. The advantage is that you get to keep the bees and and that you make sure their productivity – their honey gathering potential – does not literally fly out the front door. The telling problem is that, having too many hives or paying them too little attention, will amount to a case of too little too late. Too late, that is, when the measures you take are implemented after the bees have swarmed.

Eleventh Century 1000-1025 illustration of swarming from Exultet Rolls

of southern Italy (Bari, Archivio del Capitolo Metropolitano, Exultet 1)

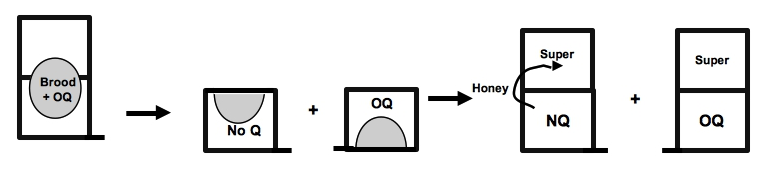

Trick 1 Splitting the colony

Let’s say you have a double or triple hive that is boiling over, that is it has lots of brood in two supers – or has completely filled out a single-box brood nest – and that bees cover most frames all under prime spring conditions. That can be any time from very early spring until mid November. Those bees, even with a young queen, are emphatically swarm-prone. Whether or not swarm cells are already present, simply offset a box with half the brood onto a new stand and super each colony as necessary. Appropriately this is called a split.

There is no need to find the queen though things get pretty complex if swarm cells are already present. Under this circumstance, the queen will need finding and a single cell should be left with the queenless colony split off.

In the normal circumstance however, one of the splits – the one without the queen – will promptly set to and raise a new queen under the emergency queen raising impulse. Well within a day, the queenless colony will have flared worker cells signalling their intent to raise a new queen from eggs laid by the old queen, eggs that have just hatched. Randy Oliver at Scientific Beekeeping says it’s worth checking the split with queen cells and then to remove all but one ‘good looking’ cell by around day ten. Occasionally the swarming impulse will persist so there is a risk of the split itself swarming if extra cells are not removed.

The Colony Split

To give the queenless split the best chance of building good emergency queen cells, position the two splits so they will both receive returning field bees in equal measure. Better, if the queen is seen, the queenless unit can be set on the parent hive site – the queenright unit being offset at least a metre – to allow bee drift and to maximise its strength and its cell building capacity.

If you are lucky enough to find another colony with supersedure cells – there are usually no more than 3 or 4 [if the colony is on the point of swarming there will be a large number of cells] – you can split strong colonies and supply each queenless split with a mature well-built queen cell. The split will have a new laying queen within days, but check her progress in the colony before accepting that she is performing satisfactorily.

Combining colony splitting with requeening

Of course you can time splits to coincide with the arrival of mailed caged queens. But this assumes you are very well organised. If you can work this magic the queenless split will get a jump start. The alternative is to take a couple of frames of mainly sealed brood and stores from strong colonies and drop them into small 3-6 frame ‘nucleus hives’ – without old queens – to accommodate new queens as they arrive.

These actions will achieve the dual goals of controlling swarming and requeening and will avert any break in the brood cycle. The bonus is that you keep the old queen laying until the new queen has taken, a much better proposition than killing the old queen and risking failure of queen introduction.

Uniting the splits

At a suitable time, ideally by late October, simply remove the old queen and unite the two splits – after removing the old queen — by papering the colony with the new queen on top. You will then have an exceptionally strong colony headed by a young and prolific queen leading into the main honey flow. Two queens laying for say three weeks before uniting will easily outstrip a similar colony that is not split and that, miraculously, doesn’t swarm.

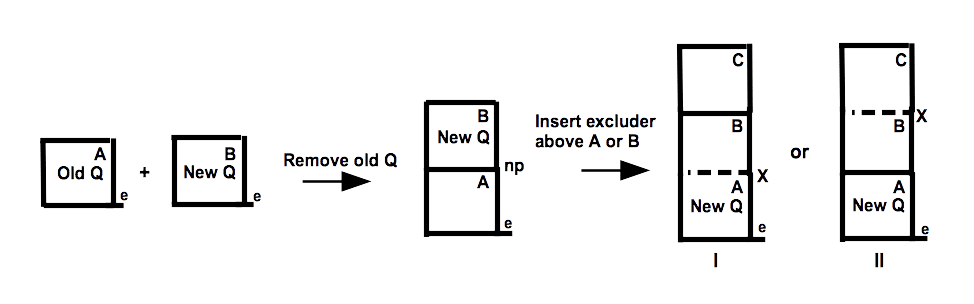

Add honey supers as needed, ideally above an excluder. The choice is yours as whether you want to run one [I] or two [II] brood boxes. If you insert an excluder above the bottom brood box [A] either find and locate the queen below or, to avoid having tho find the queen, shake the bees down from the upper brood box [B]. The queen will be confined below the excluder, though you may not see her, while nurse bees will quickly move up through the excluder to tend and keep brood warm.

One brood box is adequate if you run ten-frame gear or if you run nine frames in the now standard Paradise super. We’ve mainly run eight-frame gear and enjoy the flexibility of running double brood boxes, as have American beekeepers done traditionally. By running a double brood box, we find we can reverse the two boxes regularly leading into the honey flow and that we can avoid any need to move frames of sealed brood above the excluder during the flow.

Requeening using well-established new queens

A few more nuanced procedures

As an alternative to having to locate the old queen, you can simply place the unit with the new queen on top relying on the new queen to supersede the old queen below, a reasonable option if you have a very large apiary and raise your own queens. However we are hobby beekeepers there is always some risk you will lose the new queen so we’ve always found it preferable not to gamble with purchased stock.

A much better option is employ the same trick employed above, to move the box with the old queen [A] a couple of meters sideways and come back after an hour of two. The field bees will have drifted to the colony with the new queen [B] allowing you to quickly and locate and remove her before uniting the bees.

But let’s get back to stand alone swarm control.

Trick 2 – The Demaree

The very ingenious and very articulate George Demaree added grist to the mill by coming up with a marvellous swarm control plan, one he proclaimed in his 1892 oration to the Ohio State Beekeeping Convention in Kentuckyvii. The plan he outlined shimmers swarming. All that you need to do is to add a super (assuming you still have just a double) and move all the brood, excepting one frame up with some young brood, to the top super above an excluder. This leaves the old queen with a severely depleted brood nest in the bottom box. Shake bees down to the bottom box if finding the queen proves fruitless.

The Demaree Plan

All you need is a queen excluder and a spare super, no extra bottom board or lid though the process may need repeating after around three weeks if the brood box is laid out and swarming conditions persist.

The elegance of this scheme is that it keeps all the bees together. The queen and her retinue in the bottom box is for all the world like the departing swarm, almost no brood and in desperate need to rebuild. It abandons all attempts to swarm, just as occurs in a swarm settling in a new location.

Queen with her retinue in club observation hive May 2019

Meanwhile the queenless upper brood box behaves very like the colony that has just swarmed. While it may attempt to raise a new queen (you lift the lid a week to ten days later and remove any queen cells) it no longer has the resources or incentive to swarm.

Again care is needed as Demareeing can’t be conducted before bees are strong enough to cover brood in the now divided brood nest. The risk is that of brood chilling seriously setting the bees back.

The only disadvantage of the Demaree plan is that it may need repeating once or twice, say every 3-4 weeks until the risk of swarming is over. Unless room is provided for the queen to lay and for nectar to be ripened and stored, the crowded conditions that made the colony swarm-prone will return. As we have seen bees heading out the front door (swarming) means donating most of your honey to the nuisance swarm that has invaded your neighbour’s empty barrel or worse brick wall.

We have emphasised that bees are destined to swarm. It’s the only way, when you look at bees at a landscape scale, they can maintain a wild population replacing losses of hives to starvation and disease exacerbated by a tough seasons like the one just pastviii. In a commercial apiary or with neighbours or public anxious about bee swarms, working with bees to produce honey, not errant bees, is imperative.

And of course there are other means to control swarming, not least the almost forgotten practices of shook swarming and running two-queen hives, but those are specialist practices that we can well leave alone.

Preparations for the flow

It would be a pity, having done all that hard work requeening, building bees to maximum strength and artfully prevented swarming, not to realise a full harvest. That amounts to strategic honey removal and smart supering, something we did well for the club this past abysmal [2018-2019] season. We got all the honey off if under less than ideal conditions but only when is became quite clear there was enough to harvest. In the previous bumper season we did two extractions, but were constrained by the timing of ‘club apiary harvesting events’. In any commercial operation the dollars and honey would have come off as fast as supers were filled.

This brings us to two final facets of managing bees to maximise honey harvest. The first is to under-super to allow top supers to fill quickly, when they, any full supers, should be promptly removed. The new or extracted supers will provide space for bees to ripen and store honey. Get any extracted combs straight back on to allow them to be quickly cleaned up and refilled.

We might conclude with a simple observation: ‘a handful of well-managed hives’ will always outperform double that number of neglected hives’. The satisfaction of having healthy well-managed bees and a larder full of honey and well pollinated pumpkins is something no politician can match or promise.

But don’t trust these old fisher-persons with tales of larger that average fish or putative rivers of honey. Find out for yourself and watch your bees to hear what they tell you, just as you did when you established your first swarm.

Readings

iFarrar, C.L. (1944). Productive management of honeybee colonies in the Northern States. Circular no. 702, 2 July 1944, Washington, D.C. United States Department of Agriculture 28pp. http://www.nnjbees.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Productive-management-of-honeybee-colonies-Farrar.pdf and https://archive.org/details/productivemanage702farr and https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112019274536 and Farrar, C.L. (1968). Productive management of honey-bee colonies. American Bee Journal 108(3):95-97; 141-143. and Farrar, C.L. (1968). Productive management of honey-bee colonies. Apiacta 4:22-28.

iiClayton Leon Farrar (1968). Productive management of honey-bee colonies. American Bee Journal 108(3):95-97; 141-143.

and Farrar, C.L. (1968). Productive management of honey-bee colonies. Apiacta 4:22-28.

iiiEverett Franklin Phillips, Ph.D. (1915). Beekeeping: a discussion of the life of the honeybee and of the production of honey, 520 pp, Preface p.vii. Bee Culture Investigations, Bureau of Entomology, United States Department of Agriculture. The Rural Science Series Bailey, L.H. (Ed.), Preface p.vii. The Macmillan Company London: Macmillan & Co., Ltd. https://victoriancollections.net.au/media/collectors/51d110e42162ef12e06aa06b/items/5341f5212162ef0a845d5a79/item-media/5341f6e42162ef0a845d648d/original.pdf

ivHuber, F. (1806). New observations on the natural history of bees, Volume I by François Huber. Letters to M. Bonnet. These letters written between 1787 and 1791 were not published until 1806. http://www.bushfarms.com/huber.htm and http://www.gutenberg.org/files/26457/

vDzierżoń, J. (1882). Dzierzon’s rational beekeeping or The theory and the practice of Dr. Dzierzon. Translated by Dirk and Stutterd, Houlston & Sons, Paternoster Square, Southall: Abbott, Bros. http://reader.library.cornell.edu/docviewer/digital?id=hivebees5017629#page/1/mode/1up

viAn unsurpassed account on swarming is provided by Geo S. Demuth. Demuth, G.S. (1921). Swarm Control. Farmers Bulletin 1198:1-45. https://ia601401.us.archive.org/32/items/CAT87202908/farmbul1198.pdf

viiDemaree, G.W. (1892). How to prevent swarming. American Bee Journal 29(17):545-546. http://bees.library.cornell.edu/cgi/t/text/pageviewer-idx?c=bees;cc=bees;rgn=full%20text;idno=6366245_6511_017;didno=6366245_6511_017;view=image;seq=17;node=6366245_6511_017%3A3.2;page=root;size=s;frm=frameset and https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/61873#page/367/mode/1up

viiiListen to Tom Seeley’s podcast on behaviour of bees in the wild and their swarming proclivity. http://beekeepingtodaypodcast.com/dr-tom-d-seeley-honey-bees-in-the-wild-019

Be the first to comment