Alan Wade

Last month we discussed why bees swarm and the difference between swarming (simple queen replacement) and supersedure (colony fission to establish a new colony). We then went on to explore simple swarm control practices, Super Reversal and the The Colony Split, all pretty straightforward practices that are very widely used by seasoned beekeepers, well at least in the Langstroth system of hive management.

For other systems of keeping bees, practices such as setting up offset Warré nucs or removing frames of honey from top bar colonies or transferring brood to weaker colonies can achieve the same purpose especially if colonies are crowded. And if you are a natural beekeeper and choose to let your bees swarm, well check out good advice from Tom Seeley on Darwinian Beekeeping (see Readings).

A more intriguing approach to swarm control is the The Demaree Plan. It is well worth mastering and it will save you that endless problem of suddenly creating too many hives and wondering why your spouse has become the bee widow or honey’d widower.

The Demaree Plan

George Demaree was an exceptionally astute beekeeper. The swarm control paper he delivered to the 1892 Ohio State University Convention in Kentucky (see Readings) is both lucid and ingenious in both its detail and content.

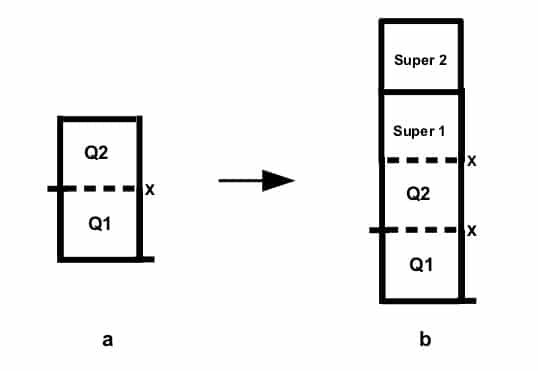

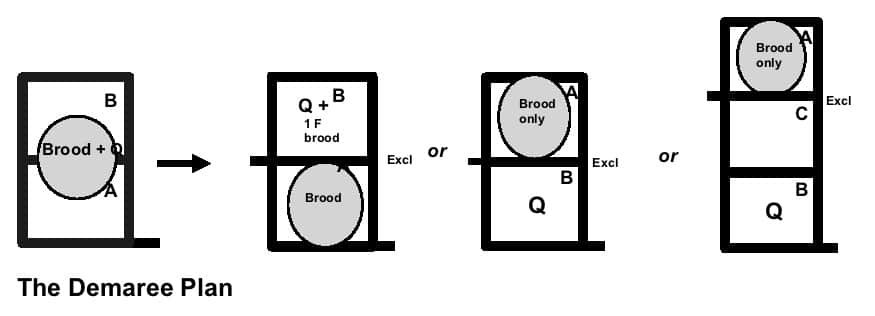

The Demaree Plan is very simple to master despite rumour to the contrary. It involves separating the queen from all but a single frame of her brood and it employs the simplest piece of gear – a queen excluder, no more – to to put the queen in a near brood-free condition. Nurse bees join the queen, but only as needed, while any excess honey located near the brood nest is moved up into the super to replicate the Super Reversal scenario we’ve already visited. Idle bees are put back to work. If you look the diagram closely you’ll see that the system looks eerily like swarming. That’s why it works.

An attractive variant of the The Demaree Plan involves shaking all frames into the lower super or in front of the colony and putting all the brood up top so that the queen does not need to be found. This way any queen cells that develop will all be in the upper brood nest and frames can be examined without having to remove the top super. An additional super, placed above the old brood nest, will further separate the the old queen from her brood, will keep bees busy and will facilitate colony expansion.

What Demaree forgot to mention was that it is essential to go back to the split queenless broodnest 7-10 days afterwards – no later – to remove queen cells that develop, supersedure style, in the brood nest to prevent swarming. We reckon that if beekeepers were to adopt The Demaree Plan there would be heaps more honey and collecting swarms would be about as common as finding hen’s teeth.

Another note of warning. Both Super Reversal and The Demaree Plan delay, rather than entirely avert, swarming. So keep a close watch and, if needed repeat the process say 3-4 weeks later when the bees may again attempt to swarm.

However attempting to use The Demaree Plan too early in the season before the weather warms up and before the colony builds up can be disastrous. By jumping the gun you will simply chill brood, put the colony back and get no swarm control benefit.

The net result of the The Demaree Plan is the production of a hive much stronger than the original colony even had it never swarmed. Its advantage over colony splitting is that there is no interruption in brood rearing and that the colony is maintained as single functioning unit.

Requeening to Head Off Swarming

One of the surest ways to discourage swarming is to regularly requeen your bees. Colonies with queens more than eighteen months old are about twice as likely as unmanaged colonies to swarm. In addition colonies that have requeened themselves (supersedure queens), colonies headed by queens that have swarmed previously or that you have established from swarms are more likely to swarm than those headed by young queens raised by top-line queen breeders.

There are also differences between honey bee races in swarming propensity (Italian bees are seemingly less swarm prone) but each queen breeder will have different stock, and every queen will be different. Getting a good queen is always an ‘odds game’ though all reputable breeders swamp their mating yards with drones from so-called drone mother colonies of good stock and all make sure their breeding stock is well fed, a necessary condition for producing top quality queens.

In practice most beekeepers requeen in mid-to-late spring when queens are most readily available and before bees build up and make the job too challenging. But there is a very good case to conduct requeening in autumn. This is because colonies with old queens are more likely to fail over winter and because queens almost cease laying and hence don’t age physiologically during the break. They then commence laying earlier than do older queens and are less likely to swarm before queens become available in spring.

But when to requeen is to split hairs. A poor queen should always be replaced, that is if you can find a good one. Having good quality young stock, providing adequate space for the queen to lay and for the bees to put stores of honey and pollen away will anyway minimise the risk of swarming.

Readings

Demaree, G.W. (1892). How to prevent swarming. American Bee Journal 27(17): 545-546. http://bees.library.cornell.edu/cgi/t/text/pageviewer-idx?c=bees;cc=bees;rgn=full%20text;idno=6366245_6511_017;didno=6366245_6511_017;view=image;seq=17;node=6366245_6511_017%3A3.2;page=root;size=s;frm=frameset

Seeley, T. (2017). Darwinian beekeeping: An-evolutionary approach to apiculture. http://www.naturalbeekeepingtrust.org/darwinian-beekeeping

Be the first to comment