Alan Wade

A remarkable feature of members of the social stinging wasp family is that they behave very much like the social corbiculate bees. However to obtain any semblance of how these two social groups relate to one another we need first to reflect on the fact that both the stinging wasp and bee families are comprised almost entirely of solitary taxa. Importantly they are populated by islands of highly eusocial insect tribes.

Wasp and bee origins

To track wasp and bee origins we must start at the top of the insect hymenoptera order. These are the lacy winged, narrow waisted insects that originated in the Lower Triassic, 247-253 million years ago (mya). Today they total more than 100,000 species. According to The Australian Museumi there are of the order of 1275 ant and 10,000 wasp species in Australia alone – some claim three times more – and just 176 sawflies. The bees separated from a predatory wasp ancestor about 120 million years ago, switching their diet purely to flower pollen and nectar. Seven bee families emerged from this ancestor between 110 and 65 mya.ii

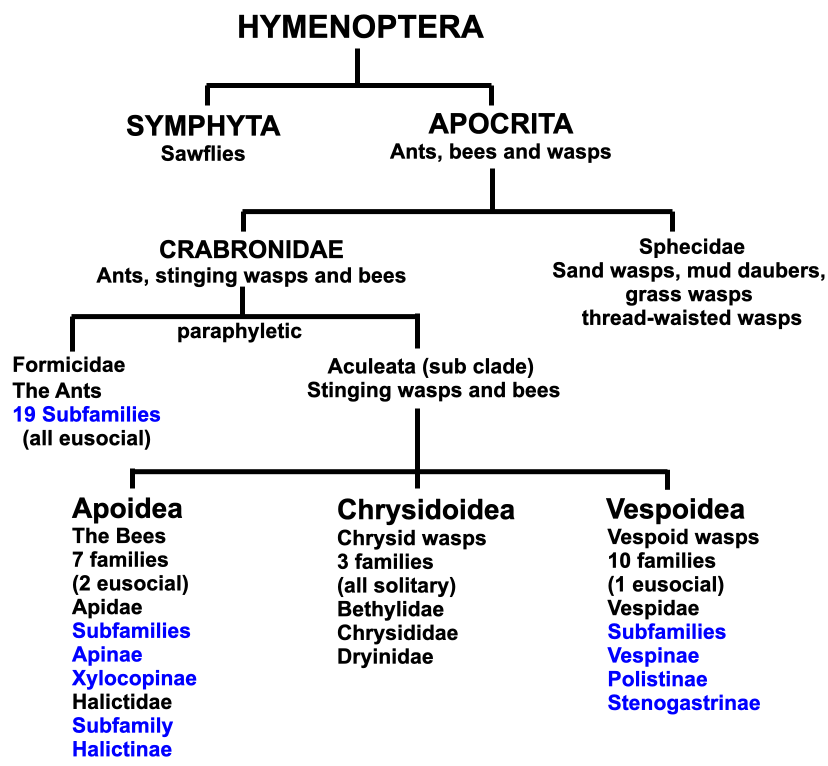

Eusocial hymenoptera, ants apart, are restricted to the sub clade Aculeata (Figure 1).iii Excluding also the solitary chrysid wasps (super family Chrysidoidea) – parasites or cleptoparasites, the stealing wasps of other insects – we are left with two super families, the bees (the Apoidea) and the stinging wasps (the Vespoidea) that contain all the eusocial taxa.

Let’s narrow this listing further. The wasp family Vespidae, the vespid wasps, is the solitary repository of all the eusocial wasps whilst the bee family Apidae contains nearly all the eusocial bees. There is also a number of primitively eusocial sweat bees in the bee family Halictidae. For the most part we can restrict ourselves to just two standout hymenopteran subfamilies, the vespine, polistine and stenogastrine (vespid) wasps and the apine (corbiculate) bees buried further in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Eusocial ant, bee and wasp subfamilies highlighted in blue.

Without delving further into their timelines or their complex evolutionary pathways we can focus on their shared eusocial attributes. Most notable are their reliance on a worker class to do the heavy lifting, the independent inventions of comb constructed on hexagonal cell and globular cell plans and the parallel evolution of total social interdependency. Apart from very primitive facultatively eusocial xylocopine and halictine bee taxa, those that can adopt either a solitary lifestyle or behave as eusocial insects, there are two distinctive forms of hyper sociality.

Firstly there are the obligate and permanently eusocial taxa typified by the honey and stingless bees and by some wasps, notably examples of which include the paper bag wasp Ropalidia romandi – maybe other species – and the night flying Provespa wasps. They propagate by colony fission. In more common parlance we call this reproductive swarming. However, as always, there are exceptions. As an example, tropical colonies of the lesser banded hornet Vespa affinis also propagate by swarming as well as by founding queens, the latter exclusively so in more temperate regions.iv

Among the majority of the advanced social wasps, and the non parasitic bumble bees, this alliance is ephemeral. While also obligately eusocial they are only so for part of their lifecycle. Instead of overwintering as a unit, the colony adopts a strategy of producing a large number of queens and drones. The colony then dwindles and dies, the many solitary queens going into diapause to overwinter alone (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Solitary female German wasp, Vespula germanica, found in author’s fire woodpile 2 July 2023 (southern hemisphere winter).

At spring’s awakening foundress queens forage and provision one-to-a-few generations of offspring as must any solitary insect. However instead of producing sexual reproductives the queen first generates a clutch of sterile female workers that, upon emergence, take over all nest and harvesting duties. The colony then switches to become a cooperative community with a clearly defined division of labour, its ultimate purpose being to produce large numbers of queens and drones needed to repeat the cycle.

These reproductive strategies, swarming and producing many queens, are not always sharply delineated. Some ants, bees and wasps are programmed to employ both strategies largely in response to resource availability and climatic factors.

Let’s move on from the exigencies of survival and reproduction of eusocial wasps and bees. Let’s talk about wasps.

The antiquity of social wasps

That eusociality is rare in evolutionary terms is signalled by the fact that only relatively few families of wasps and bees contain such taxa. All other insect orders, excluding a few beetles, aphids and thrips, are entirely solitary. Full details of how eusociality arose is one of the mysteries of nature:v

…true sociality in animals, in which sterile individuals work to further the reproductive success of others, is found in termites, ambrosia beetles, gall-dwelling aphids, thrips, marine sponge-dwelling shrimp (Synalpheus regalis), naked mole-rats (Heterocephalus glaber), and the insect order Hymenoptera which includes bees, wasps, and ants.

For those unsure of the validity of this reality check out the number wasps and ants pestering you at the next family picnic.

Eusocial wasps all belong to the super family Vespoidea (~ 28,000 species) the so-called stinging wasps and are found in one family: the Vespidae (vespid wasps) comprising the Vespinae (vespine wasps), the Polistinae (paper wasps) and the Stenogastrinae (hover wasps). Eusocial bee species are restricted to just two families, the Apidae (corbiculate and carpenter bees) and the Halictidae (sweat bees) both of truly ancient origin (Table 1).

| Eusocial Taxa | Eusocial progenitors | Origin date (mya) | Number of queen mates | Number of species |

| Ants (Formicidae) | 1 | 115-135 | 1 | 12,000 |

| Vespid wasps (Vespidae) | ~80 | 860 | ||

| Vespine wasps [Vespinae] (Vespidae) | 1 | ~80 | Usually 1 2 in Vespula spp. | 67 |

| Polistine wasps [Polistinae] (Vespidae) | 1 | ~80 | 1 to several | 300 |

| Stenogastrine hover wasps [Stenogastrinae] (Vespidae) | 1 | ~80 | 1 (occasionally more e.g. Parischnogaster spp, Liostenogaster vechti) | 45 |

| Apid bees (Apidae) | 1 | 78-95 | >1000 | |

| Apine corbiculate bees [Apinae] (Apidae) | 1 | 78-95 Apini (56-61) Meliponini (12-21) Bombini (28-35) Euglossini (65) | 8-44 in Apis 1 (e.g.Tetragonula-Austroplebeia)1-3 in Bombus 1 (some social) | 12 (Apini) 550 (Meliponini) 250 (Bombini, not all eusocial) >700 (Euglossini, some social) |

| Xylocopine carpenter bees [Xylocopinae] (Apidae) | 1? | 500 (1 sp eusocial in tribe Ceratinini and 2 spp in tribe Allodapini) | ||

| Halictine sweat bees [Halictinae] (Halictidae) | 3 | 15-28 | Usually 1 1-3 in Halictus | 4500 (Many primitively eusocial species in Halictini and Augochlorini tribes) |

Table 1 Ant, wasp and bee origins and diversity metrics.

The social wasps

In terms of the number of species, the social wasps are less diverse than the ants but on a par with the bees. Wasp nest structures, the non-living component of the colony, are constructed of flat or domed comb(s) built in the open (e.g. Polistes) and egg-shaped nests (e.g. Dolichovespula), others are subterranean or cavity dwelling. Some but by no means all species encase themselves in a weather proofing envelope, examples of which include the nests of the subterranean European wasp, the hanging paper bag wasps and the aerial northern hemisphere yellowjackets. Nesting materials range from mud (stenogastrine wasps) to plant fibres (vespine and paper wasps). Most social wasps employ their cells for the sole purpose of raising brood though some store small reserves of nectar and macerated insect prey or even live spiders: honey bees, stingless bees and bumblebees, on the other hand, employ often specialised cells for longer-term storage of cured nectar and pollen.

The vespid wasps: Family Vespidaevi (Superfamily Vespoidea)

As noted, the eusocial vespid wasps belong to three subfamilies: Vespinae (vespine wasps), Polistinae (paper wasps) and Stenogastrinae (hover wasps)

Common genera of the vespine wasps include the exotic [for the southern hemisphere] Vespula wasps (e.g. the European wasp Vespula germanica widely distributed in eastern and south western Australia and the common wasp Vespula vulgaris), Hornets (Vespa, notably voracious Asian species) and the northern hemisphere Aerial yellowjackets (Dolichovespula).

Vespula wasps: Vespula spp

This is a small genus of twenty three wasps of which the European or German and common wasp are now very widespread globally and are generally a problem for native insects as well as for honey bees.

The story of their spread to the southern hemisphere is illustrated by the European wasp (Vespula germanica) that was first detected in Tasmania in 1959 and is now widespread in south-eastern Australia, southern South Australia and smaller areas in south-western Western Australia. It is widely distributed in the temperate zones of Europe, the Americas and elsewhere and even in the tropics at elevated locations, e.g. The Cameron Highlands in West Malaysia.

Spradberyvii reports that European wasp colonies are established from overwintered queens – I have found a number in stored material in our bee shed: this method of annual establishment from founding queens is nearly universal amongst social wasps. Those commenced annually build to populations varying in size from about 500 to 3000 individuals. The European wasp was first detected in New Zealand in 1922 and it seems likely that separate incursions to Australia came from there in imported cargo. Thomasviii reports a New Zealand colony containing of 11,900 wasps. However Australian colonies that overwinter can reach of much greater proportions, the Australian Museum recording a colony with over 100,000 wasps.ix

Vespula wasps nest underground in a horizontal multiple comb arrangement (Figure 3) further encased in a papery envelope located at the end of a short narrow passageway. The British Pest Control Association presents an excellent image of hexagonal comb with developing larvae (Figure 4) of the European wasp.

Figure 3 Vespula germanica layered combs encased in a mud and fibre envelope.x

Figure 4 Vespula germanica comb structure with larvae.xi

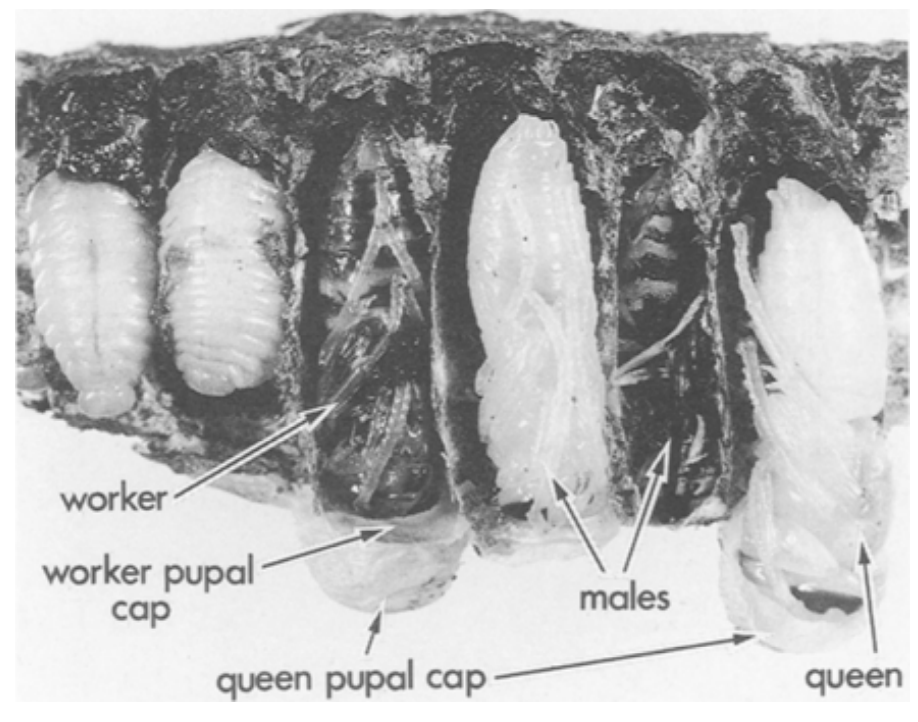

Spradbery describes the nest structure and cell sizes, as well as detailed seasonal dynamics of brood in all stages of development for the European wasp Vespula germanica (Table 2) and for the smaller Vespula vulgaris (Table 3).xii Both species are common around Melbourne where Vespula vulgaris was originally confused with the more widely distributed Vespula germanica.xiii Towards the end of the season, the European wasp colony constructs cells that are 21% larger than worker cells (twice the volume and 17% greater diameter at the comb face) to raise both queens and drones (Figure 5). These wasps also raise smaller queens and drones in worker cells, an atypical behaviour shared with the aerial yellowjacket, Dolichovespula arenarea.

| Cell type | Width (mm) | Depth (mm) |

| Queen | 6.65±0.09 | 21.94±0.21 |

| Drone | 6.66±0.06 | 17.52±0.36 |

| Worker | 4.96±006 | 18.03±0.17 |

Table 2 Queen, drone and worker cell sizes for Vespula germanica.xiv

| Cell type | Width (mm) | Depth (mm) | ||

| Mean | Range | Mean | Range | |

| Queen | 6.27 | 6.0-6.5 | 14.18 | 12.8-15.3 |

| Worker | 4.51 | 4.0-6.1 | 13.72 | 11.4-17.3 |

Table 3 Queen and worker cell sizes for Vespula vulgaris.xv

Figure 5 Transverse section of Vespula germanica brood comb (after Spradbery 1993).

Vespula wasps are both scavengers of dead bees and also take lives bees and noticeably dart in and take bees during honey bee hive inspections. They are a notable problem in queen breeder apiaries where slow moving queens on mating flights are easy prey.

Aerial yellowjackets: Dolichovespula spp

Dolichovespula is another genus of black or yellow-faced wasps found in much of the northern hemisphere. They are about twenty four species and are similar in most respects to Vespula but are typically much longer faced (Figure 6). Nests are egg-shaped (Figure 7) and are located in trees or attached to dwellings. The nests are encased in multiple-layered papery shellsxvi containing horizontal combs with typical hexagonal cells hanging below the comb face.

Figure 6 Bald-faced hornet, Dolichovespula maculata widespread in temperate North America.xvii

Figure 7 Bald-faced hornet, Dolichovespula maculata nest attached to tree branch.xviii

Aerial yellowjackets are comparable in size to Vespula, the Bald-faced hornet being 13 mm long and the queens rather larger at 20 mm.

Hornets:xix Vespa orientalis, mandarinia

Hornets are large and often aggressive wasps predating on a variety of insects, not least flies, cockroaches and bees. The giant Asian hornet Vespa mandarinia reaches up to 55 mm in length and is suspected of causing the Giant mountain honey bee, Apis laboriosa, another formidable stinging insect, to abscondxx. Its predation on both Apis mellifera and Apis cerana colonies in Japan is well documented.xxi Most hornets are well known for destroying honey bee colonies, selectively decapitating guard bees, invading colonies and removing all bees and brood.

Moreover the Lord thy God will send the hornet among them,

until they that are left, and hide themselves from thee, be destroyed.

Deuteronomy 7:20

There are twenty two Vespa species known from Europe, Africa, Europe and Asia, five of which are regarded as being of particular concern (Table 4).

| Hornet species | Common name | Nest | Population |

| Vespa velutina | Asian hornet | Suspended paper nest | ~ 430 (up to over 1000) |

| Vespa crabroxxii | European hornet | Paper nest in hollows | 200-400 (up to 1000) |

| Vespa orientalis | Oriental hornet | Paper nest underground or in cavities | ~ 2000 |

| Vespa affinisxxiii | Lesser banded hornet | Paper nest mainly in trees | very variable and polygynous (1-5 queens) in tropics |

| Vespa mandariniaxxiv | Asian giant hornet | Subterranean nesting | ~300 |

Table 4 Size and origin of common Vespa wasps.

The brood development times and size of nest for these species varies considerably (Table 5), the size of the insects being similarly variable within and between species (Table 6) and even seasonally.

| Hornet species | Common name | Egg | Larva | Pupa | Total | No. combs | No. cells | Cell diameter (mm) | Cell depth (mm) | Worker size* (mm) | ||

| Small | Large | Small | Large | |||||||||

| Vespa velutinaxxv | Asian hornet | 13 | 16 | 19 | 48 | 2-11 | 590-6200 | ns | ns | ns | ns | 20 [30, 24] |

| Vespa crabroxxvi | European hornet | 5-18 | 9-19 | 13-15 | 27-51 | 3-33 | 595-6600; 1500-3000 | ns | ns | ns | ns | 25 [35, <25] |

| Vespa orientalisxxvii | Oriental hornet | 5-6 | 15-24 | 15-16 | 36-45 | 1-6; 3-6 | 600-4200; 600-900 | 7 | 9 | 16-18 | 22-24 | 25-35 |

| Vespa affinisxxviii | Lesser banded hornet | 6-7 | 15 | 15-20 | 36-41 | 5-9 | 1060-45,000 | ns | ns | ns | ns | 25 [30, 26} |

| Vespa mandariniaxxix | Asian giant hornet | – | – | – | 38 | 5 | 675-4700 | ns | ns | ns | 35-39 [<50, 35-39]] | |

Table 5 Seasonally variable brood development of common Vespa wasps:xxx also variable with nest development stage, number of nests examined and geographical location.

Note: In early nest development stage, smaller cells and wasps are produced.

[Queen, drone sizes]

| Hornet species | Common name | Length (mm)xxxi | Queen (mm) | Drone (mm) | Worker (mm) | Origin |

| Vespa velutinaxxxii | Asian hornet | 17-32 | 30 | 24 | 20 | Southern China |

| Vespa crabroxxxiii | European hornet | 18-23 | 35 | ? | 25 | Europe |

| Vespa orientalisxxxiv | Oriental hornet | 18-23 25-35 | ? | ? | ? | SW Asia, NE Africa, Madagascar |

| Vespa affinisxxxv | Lesser banded hornet | 22-25 (queens 30) | 30 | 20-27 | 20-27 | Asia, tropical and subtropical |

| Vespa mandariniaxxxvi | Asian giant hornet | 55 (wingspan 76) | 50 | 38 | 35-40 | Tropical East Asia, South Asia, Mainland Southeast Asia, Russian Far East |

Table 6 Characteristic sizes of Vespa wasps.

Like honey bees, a few Vespa species have a natural wide climatic range. For example the Lesser Banded Hornet has both tropical tropical and temperate races. Michael Archer provides an excellent summary of the biology of Provespa and Vespa wasps including detailed notes on their natural distribution and global spread, their genetic variability, nesting behaviour, larval development and seasonal population dynamics.

The Polistine wasps (Polistinae: Vespidae): Polistes, Ropalidia

There are two genera of social polestine wasps comprising some forty three species in Australia, and some 800 in these and other genera worldwide.xxxvii

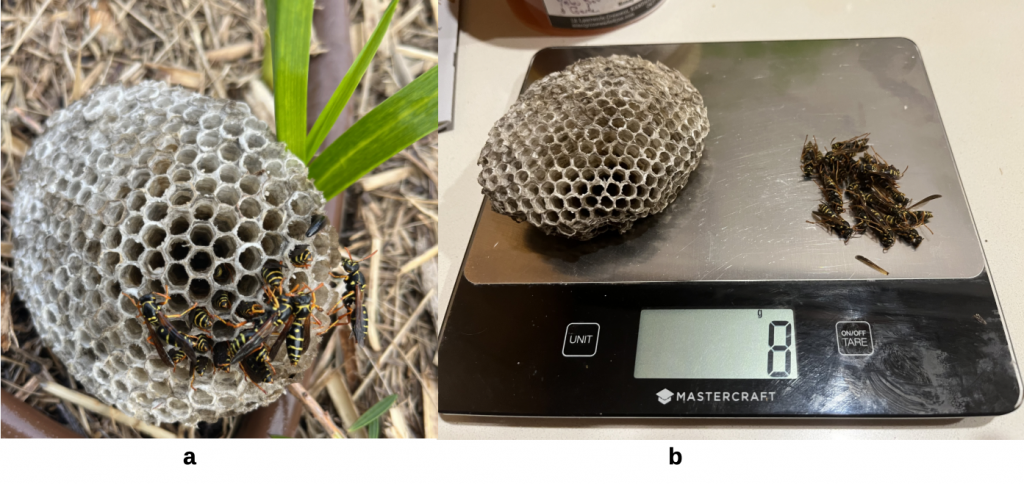

The Australian Paper Wasp Polistes humilis is widespreadxxxviii but has been largely replaced by Polistes chinensis in the Canberra region. As with most social wasp species, Polistes nests are constructed from chewed plant material mixed with saliva and propolis. Paper wasps nests are constructed as an inverted umbrella attached to an overhanging substrate by a short pedicel (stem). Queens and workers are of the same size. Roughly circular domed nests may reach a total count up to ~ 400 cells. Polistes chinensis colonies tend to be larger than those of Polistes humilis though the percentage of cells occupied by pre-emerging larvae varying between 54 and 64% in the peak brood raising month of January.xxxix Colony size is dependent on local conditions, colonies sometimes employing old comb in nest reestablishment in spring. Both males and females overwinter as pupae though males emerge later in the season.

In warmer climes Polistes colonies may overwinter with several queens. In one study of the native Polistes humilis, Cumberxl records nest sizes varying widely containing from 20-30 to over 1000 cells (nest size (290 x 110 mm2) where he found up 400 larvae or ~ 35% occupancy.

Here are measurements of a late season Chinese paper wasp nest (Polistes chinensis) I collected in Canberra in late autumn 2023 (Table 7). The colony was in typical late season decline and broodless (Figure 8) and contained several, likely male, wasps with longer wings and wider gasters (abdomens).

| Colony feature | Size | Weight | Number of combs |

| Nest | 100x80x20 mm3 (domed to 25 mm total) | 5 g | single comb |

| Pedicel | 5 mm | ||

| Drone* | 15 mm | 3 | |

| Worker | 13-14 mm | 130 mg | 16 (possibly all queens) |

| Cells | 5.5 mm dia. | 376 (~20+ old cells) |

Table 7 Paper wasp (Polistes chinensis) late season broodless nest metrics.

Note: Abdomen wider on three insects, wings extending beyond last tergite.

*Only males are produced from mid-to-late summer: queens and workers are morphologically identical.

Figure 8 Chinese paper wasp nest 11 May 2023:

(a) in garden at Echo Place Lyons ACT; and

(b) measuring up in kitchen.

The common Yellow brown paper bag wasp (Ropalidia romandi) of tropical eastern and northern Australia is very different to the paper wasps most of us are familiar with. And for the unwary, the paper bag is not something you will find your lunch packed in. As its name suggests the colony forms a protective envelope around the comb, extending that envelope to encompass any new comb built. And, like honey bees and stingless bees, it forms a perennial nest and is a swarm-founding as well being a solitary queen founding species. So a mature nest can be either small or quite large, though the wasp itself (Figure 9) at a length of ~12 mm is, in wasp terms, relatively small.

Figure 9 Yellow brown paper wasp Ropalidia romandi.xli

The Yellow brown paper bag wasp is also remarkable in that this species not only swarms but may contain more than a single mated egg-laying queen. Like some races of African Apis mellifera bees the paper bag wasps can also form absconding swarms where the whole colony departs in response to disturbance. And, like honey bees, the departure is orchestrated by the workers, not by the queen.

Combs are horizontal and single-sided and can reach 1 m in length. One exceptionally large nest, comprising ten combs connected by supporting pedicels, contained ~ 30,000 cells and had a comb surface area of 1950 cm2. To get a handle on this extraordinary real estate that’s equivalent to about the number of cells found in an equivalent of eight full depth Langstroth frames.

Australia has not just one but three species of Ropalidia. There are two tropical species, Ropalidia romandi, the Yellow brown paper wasp and Ropalidia revolutionalis, the Stick nest brown paper wasp, both found in northern and north eastern Australia. A further temperate zone species, Ropalidia plebeiana, the White-faced brown paper wasp, forms small colonies with several males and a number of queens. It has been found as far south as south eastern New South Wales.

As well as being a swarm-founding wasp the Yellow brown paper wasp (Ropalidia romandi) is interesting in that maintains a perennial nest (Figure 10). Yamane and Itôxlii provide details of the nest architecture of Ropalidia romandi: cells have a diameter of 2.3 ± 0.2 mm.

The genus, comprising 186 species, is widespread stretching from tropical Africa, and southern and eastern Asia to Australia. The social dynamics, colony longevity, level of subordination, queen succession and method of reproduction are so variable amongst Ropalidiaxliii that it would sometimes appear difficult to always assign social status to individual species.

Figure 10 Ropalidia romandi nest.xliv

The Stenogastrine wasps: (Stenogastrinae: Vespidae) Hover wasps

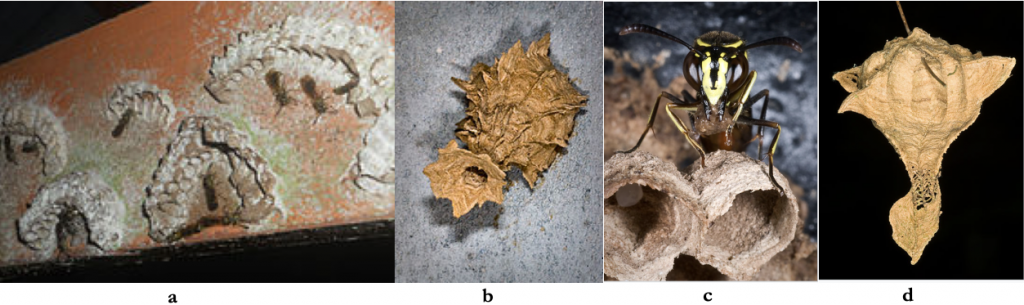

Colonies of hover wasps are usually limited to no more than ten individuals, are flexible in structure and lack the true workers of other social wasps. They are facultatively eusocial.xlv The nests are tiny and colonies have a long gestation, that is they build up very slowly. The absence of a pedicel to hang the nest from and poor nest constructing material are features that seem likely to have prevented further social evolution of hover wasps. There are seven known genera of hover wasp not all well characterised: Metischnogaster, Cochlischnogaster, Stenogaster, Anischnogaster, Liostenogaster, Parischnogaster, Eustenogaster xlvi and contain forty five species.xlvii A few nests are depicted in the following images (Figure 11) some incorporating mud as a building material.

Figure 11 Stenogastrine (hover wasp) nests attached directly to substrate.:

(a) Liostenogaster vechti colonies;

(b) Eustenogaster micans nest;

(c) Eustenogaster calyptodoma cells; and

(d) Eustenogaster fraterna nest.

We have much to learn from eusocial wasps, their role in keeping pests such as flies and cockroaches at bay, our role in spreading the more troublesome species and their remarkable social ordering.

Readings

iAustralian Museum (accessed 18 July 2023). Ants, wasps, bees and sawflies: Order Hymenoptera. https://australian.museum/learn/animals/insects/sawflies-wasps-bees-ants-hymenoptera/

iiMuseum of the Earth (2022). Evolution and fossil record of bees: Where did bees come from? https://www.museumoftheearth.org/bees/evolution-fossil-record

iiiBrothers, D.J. and Starr, C.K. (2019). Aculeate Hymenoptera: Phylogeny and classification. Encyclopedia of social insects. Springer Nature, Switzerland, pp.1-9. https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-3-319-90306-4_1-1

Brothers, D.J. and Carpenter, J.M. (1993). Phylogeny of Aculeata: Chrysidoidea and Vespoidea (Hymenoptera). Journal of Hymenoptera Research 2(1):227-304. https://archive.org/details/ants_13285/13285/mode/1up

ivWikipedia (accessed 18 July 2023). Vespa affinis. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vespa_affinis

vWikipedia (accessed 23 May 2023). Evolution of eusociality. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evolution_of_eusociality

viVariety of Life (accessed 4 May 2023). Vespidae. https://varietyoflife.com.au/vespidae/

viiSpradbery J.P. and Maywald G.F. (1992). The distribution of the European or German wasp, Vespula germanica (F.)(Hymenoptera: Vespidae), in Australia: past, present and future. Australian Journal of Zoology 40(5):495-510. https://www.publish.csiro.au/ZO/ZO9920495

viiiThomas, C.R. (1960). The European wasp (Vespula germanica Fab.) in New Zealand. New Zealand Department of Industrial Research Information Series No. 27, 74pp. https://archive.org/details/european-wasp-in-new-zealand

ixMurray, M. Australian Museum (December 2020). European wasp. https://australian.museum/learn/animals/insects/european-wasp/

xBendle, P. CitScihub. (accessed 21 May 2023). Pest advice for controlling wasps. Wasps nests (photos and text). https://www.citscihub.nz/Phil_Bendle_Collection:Wasp_nests_(Photos_and_text)

xiBendle, P. (July 2019). British Pest Control Association: Pestwatch: Life cycle of a wasp. https://bpca.org.uk/a-z-of-pest-advice/wasp-control-how-to-get-rid-of-wasps-bpca-a-z-of-pests/188976

xiiGreene, A., Akre, R.D. and Landolt, P. (1976). The aerial yellowjacket, Dolichovespula arenaria (Fab.): Nesting biology, reproductive production, and behavior (Hymenoptera: Vespidae). Melanderia 26:1-34.

xiiiKasper, M.L. Reeson, A.F. and Austin, A.D. (2008). Colony characteristics of Vespula germanica (F.) (Hymenoptera, Vespidae) in a Mediterranean climate (southern Australia). Australian Journal of Entomology 47(4):265–274. doi:10.1111/j.1440-6055.2008.00658.x

xivSpradbery, J.P. (1993). Queen brood reared in worker cells by the social wasp, Vespula germanica (F.) (Hymenoptera: Vespidae). Insectes Sociaux 40(2):181-190. doi:10.1007/bf01240706

xvSpradbery J.P. (1971). Seasonal changes in the population structure of wasp colonies (Hymenoptera: Vespidae). Journal of Animal Ecology 40(2):501-523. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3259

xviBalduf, W.V. (1954). Observations on the white-faced wasp Dolichovespula maculata (Linn)(Vespidae, Hymenoptera). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 47(3):445-458. doi:10.1093/aesa/47.3.445 https://academic.oup.com/aesa/article-abstract/47/3/445/56906?login=false

xviiPenn State University. (14 April 2023). Baldfaced hornet. https://extension.psu.edu/baldfaced-hornet

xviiiWikimedia Commons (accessed 21 May 2023). Dolichovespula maculata (bald-faced hornet) nest. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dolichovespula_maculata_(bald-faced_hornet)_nest.jpg

xixNew South Wales Department of Primary Industries (accessed 15 May 2023). Hornets. https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/biosecurity/plant/insect-pests-and-plant-diseases/hornet

xxBatra, S.W.T. (1996). Biology of Apis laboriosa Smith, a pollinator of apples at high altitude in the Great Himalaya Range of Garhwal, India, (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 69(2):177-181. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25085665

xxiMatsuura M. and Sakagami, S,F. (1973). A bionomic sketch of the giant hornet Vespa mandarinia, a serious pest for Japanese apiculture. Journal Faculty of Science 19(1):125-162. https://core.ac.uk/download/41850461.pdf

xxiiUS Department of Agriculture (June 1981). Agriculture handbook Number 552. The yellowjackets of America North of Mexico, pp.32-35. https://naldc.nal.usda.gov/download/CAT82762500/PDF

xxiiiSpradbery, J.P. (1986). Polygyny in the Vespinae with special reference to the hornet Vespa affinis Picea Buysson (Hymenoptera Vespidae) in New Guinea. Monitore Zoologico Italiano-Italian Journal of Zoology 20(1):101-118. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00269786.1986.10736493

Martin, S. J. (1992). Development of the embryo nest of Vespa affinis (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) in southern Japan. Insectes Sociaux 39(1):45-57. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227200864_Development_of_the_embryo_nest_ofVespa_affinis_Hymenoptera_Vespidae_in_Southern_Japan

xxivMatsuura, M. and Yamane, S. (1990). Biology of the vespine wasps. Springer Verlag. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267869469_Biology_of_Vespine_Wasps

xxvArcher, M.E. (1994). Taxonomy, distribution and nesting biology of the Vespa bicolor group (Hym., Vespinae). Entomologist’s Monthly Magazine 130:149-158. https://www.academia.edu/4236740/Taxonomy_distribution_and_nesting_biology_of_the_Vespa_bicolor_group_Hym_Vespinae_1994_

xxviUS Department of Agricuture (June 1981) loc. cit.

xxviiArcher, M.E. (1998). Taxonomy, distribution and nesting biology of Vespa orientalis L. (Hym., Vespidae). Entomologist’s Monthly Magazine 134:45-51. https://www.academia.edu/4236674/Taxonomy_distribution_and_nesting_biology_of_Vespa_orientalis_L_Hym_Vespidae_1998_

xxviiiArcher, M.E. (1997). Taxonomy, distribution and nesting biology of Vespa affinis (L.) and Vespa mocsaryana du Buysson (Hym., Vespinae). Entomologist’s Monthly Magazine 133:27-38. https://www.academia.edu/4236774/Taxonomy_distribution_and_nesting_biology_of_Vespa_affinis_L_and_Vespa_mocsaryana_du_Buysson_Hym_Vesoinae_1997_ https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1570572700237447040

xxixArcher, M.E. (1995). Taxonomy, distribution and nesting biology of the Vespa mandarinia group (Hym., Vespinae). Entomologist’s Monthly Magazine 131:47-53. https://www.academia.edu/4236755/Taxonomy_distribution_and_nesting_biology_of_the_Vespa_mandarinia_group_Hym_Vespinae_1995_

Gill, C., Jack, C. and Lucky, A. (May 2020). Asian giant hornet: Vespa mandarinia Smith (1852) (Insecta: Hymenoptera: Vespidae). https://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/MISC/BEES/Vespa_mandarinia.html

xxxArcher, M.E. (2008). Taxonomy, distribution and nesting biology of species of the genera Provespa Ashmead and Vespa Linnaeus (Hymenoptera, Vespidae). Entomologist’s Monthly Magazine 144:69-101. Access at Google Scholar.

xxxiNew South Wales Department of Primary Industries. loc. cit.

xxxiiWikipedia (accessed 15 May 2023). Asian hornet. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asian_hornet

Lee, J.X.Q. (10 February 2018). Vespa velutina. http://www.vespa-bicolor.net/main/vespid/vespa-velutina.htm

xxxiiiPenn State Extension (16 September 2021). European hornet. https://extension.psu.edu/european-hornet

xxxivWikipedia (accessed 14 May 2023). Oriental hornet. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oriental_hornet

xxxvLin, L.Y. (modified by Jonathan Ho Kit Ian 17 Sep 2020). Vespa affinis – Lesser banded hornet https://wiki.nus.edu.sg/display/TAX/Vespa+affinis+-+Lesser+Banded+Hornet

xxxviWikipedia (accessed 14 May 2023). Asian giant hornet. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asian_giant_hornet

xxxviiAustralian Faunal Directory (accessed 18 May 2023). Subfamily Polistinae. https://biodiversity.org.au/afd/taxa/Polistinae

xxxviiiiNaturalistAU (accessed 2 May 2023). Australian paper wasp, Polistes humilis. Sourced from Wikipedia (19 August 2019(. https://inaturalist.ala.org.au/taxa/181077-Polistes-humilis#cite_ref-nesting_10-0

xxxixClapperton, B.K. and Lo, P. (2000). Nesting biology of Asian paper wasps Polistes chinensis antennalis Peréz, and Australian paper wasps P. humilis (Fab.) (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) in northern New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Zoology 27(3):189–195. doi:10.1080/03014223.2000.9518225

xlCumber, R.A. (1951). Some observations on the biology of the Australian wasp Polistes humilis Fabr. (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) in North Auckland (New Zealand), with special reference to the nature of the worker caste. Proceedings of the Royal Entomological Society London (A) 26(1-3):11-16. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3032.1951.tb00104.x

xliWikimedia Commons (accessed 12 May 2023). Ropalidia romandi. https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ropalidia_romandi_7283.jpg#mw-jump-to-license

xliiYamane, S. and Itô, Y. (1994). Nest architecture of the Australian paper wasp Ropalidia romandi Cabeti, with a note on its developmental process (Hymenoptera: Vespidae). Psyche: A Journal of Entomology 101(3-4):145–158. doi:10.1155/1994/92839

xliiiGadagkar, R. (2021). Ropalidia. 11pp In Encyclopedia of social insects. Starr, C.K. (ed). Springer Nature, Switzerland AG. 2021. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-90306-4_102-1 https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-3-319-90306-4_102-1

xlivProfessional pest manager (1 December 2022). Ropalidia – An Australian paper wasp with a difference. https://professionalpestmanager.com/pest-control-wasps/ropalidia-an-australian-paper-wasp-with-a-difference/

xlvHines, H.M., Hunt, J.H., O’Connor, T.K., Gillespie, J.J. and Cameron, S.A. (2007). Multigene phylogeny reveals eusociality evolved twice in vespid wasps. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 104(9):3295–3299. https://www.life.illinois.edu/scameron/publications/pdfs/hines2007pnas.pdf

xlviWikipedia (accessed 18 May 2023). Stenogastrinae. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stenogastrinae

xlviiCarpenter, J.M. and Jun-ichi. K. (1996). Checklist of the species in the subfamily Stenogastrinae (Hymenoptera: Vespidae). Journal of the New York Entomological Society 104(1/2):21–36. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25010198