Alan Wade

First and foremost Don Peer knew how to produce honey. As Miksha recallsi:

One of the legendary beekeepers of western Canada, Don Peer, a Nipawin beekeeper with an entomology PhD, once told us at a bee meeting, ‘If I were king of the world, I’d make a law that every beekeeper had to own one more super for each hive of bees’.

Bees need comb space to hold wet nectar. Dr Peer was astonishingly successful. At first, he ran two-queen colonies from packages. According to Dr Eva Crane (from her book Making a Beelineii), Don Peer’s hives made up to 40 pounds [18 kg] a day:

I saw his outfit and stood on the back of a truck to reach the top supers. Such tall hives made him switch back to single-queen hives, but even then he stacked supers as high as he could reach. ‘Bees need space,’ he said…

In a subsequent note Miksha notes a record of Eva Crane meeting Doniii:

Doug took me further east to Nipawin to visit Dr Don Peer whom I had met in 1953 when he was a graduate student in Madison, Wisconsin. He had now developed large-scale beekeeping on scientific lines, and had 1000 or more hives. He bought packages of bees each spring and made two-queen colonies from pairs of them. Each of these had 90 to 100,000 bees by July, and could store 20 kg of honey a day from the main flow – mostly from legumes, alfalfa and fireweed.

These small testaments given, it seemed worthwhile to set out to unearth the contribution that this renowned late 20th Century apiarist brought to beekeeping practice. Discovering much about him has proved a challenge as he, as a commercial apiarist, published little. But his reputation and acumen matched the likes of more famous researcher/beekeepers: François Huber, Johann Dzierżoń, Clayton Farrar, Eva Crane, Colin Butler, E.W. (Egbert) Alexander, George Wells, George Demaree, , C.C. (Charles) Miller, Eugene Killion, Robert Laidlaw, Robert Banker, Roger Morse, Tom Seeley, Winston Dunham, John Holzberlein, Mykola Haydak, Gilbert Doolittle, Moses Quinby, Lorenzo Langstroth, Floyd Moeller, John Hogg and dozens more.

Ron Miksha, an associate of Don, hints at the success of the Peer outfit:ii

We stood on cold concrete in near darkness, facing row after row of neatly painted honey drums, Don Peer and I. Don pointed to a label, ‘Water White. 16.6% Moisture. 664 Pounds’ Three hundred forty two barrels of water white honey. Almost a quarter of a million pounds [133 tonnes].

‘What are you going to do with all this honey, Doctor Peer?’ I asked. This was twenty years ago, I was an earnest young man. Don Peer, the only commercial beekeeper I knew with a PhD in entomology, shrugged his shoulders. I looked to him for marketing advice. I took out a notebook. Began to write.

‘I guess we’ll sell whatever we can’t eat,’ he said.

Of course, Don finally delivered the information I needed. He gave me the names of packers and brokers and he told me what the honey market had been doing over the past few months. But all of this was long ago, at his shop in Nipawin, Saskatchewan. In those days, I was producing a hundred thousand pounds [45 tonnes] of honey a year and it was never hard to sell the stuff. Following Don’s advice, I would call a few packers in the east, send a small sample, consider the offers. A semi-truck would soon arrive at my shop and the honey disappeared within the truck’s steel walls. I never had a problem selling to Paul Doyon or Jack Grossman or Elise Gagnon. These people sent cheques when they said they would, paid the money they promised. Every time.

Don Peer published several articles arising from his doctoral dissertationv all relating to estimating the mating range of honey bee queens and to the number of times a queen mates. Using genetically recessive Cordovan – leather coloured Italian – drones and queens, Peer was able to demonstrate that queens mate – sometimes in multiple mating flights – on an average of seven times and that they readily cross-mate at distances 9.6 km (6 miles) apart. More contemporary studiesvi signal that the average is more like seventeen matings but varies widely (1-59 matings). In a subsequent study Peervii, using an isolated mating yard, was able to show that mating success dropped off as the range increases, mainly signalled by delay in delay in queens commencing to lay. This may be interpreted as queens mating to volume of semen never achieved in a few matings:

Genetically-marked virgin queen honey bees were located at various distances up to 22.5 km (14.0 miles) from an apiary stocked with genetically-marked drones in an area containing only these experimental bees.

Some matings occurred across distances up to 19.3 km (10.1 miles). With increasing distances from the drone source a decreasing percentage of queens mated successfully. Queens located at the drone source, 6.1 and 9.8 km (3.8 and 6.1 miles) distant, began laying at approximately the same time. Those located 12.9 km (8.0 miles) distant began laying later and those at 19.3 km (10.1 miles) later still.

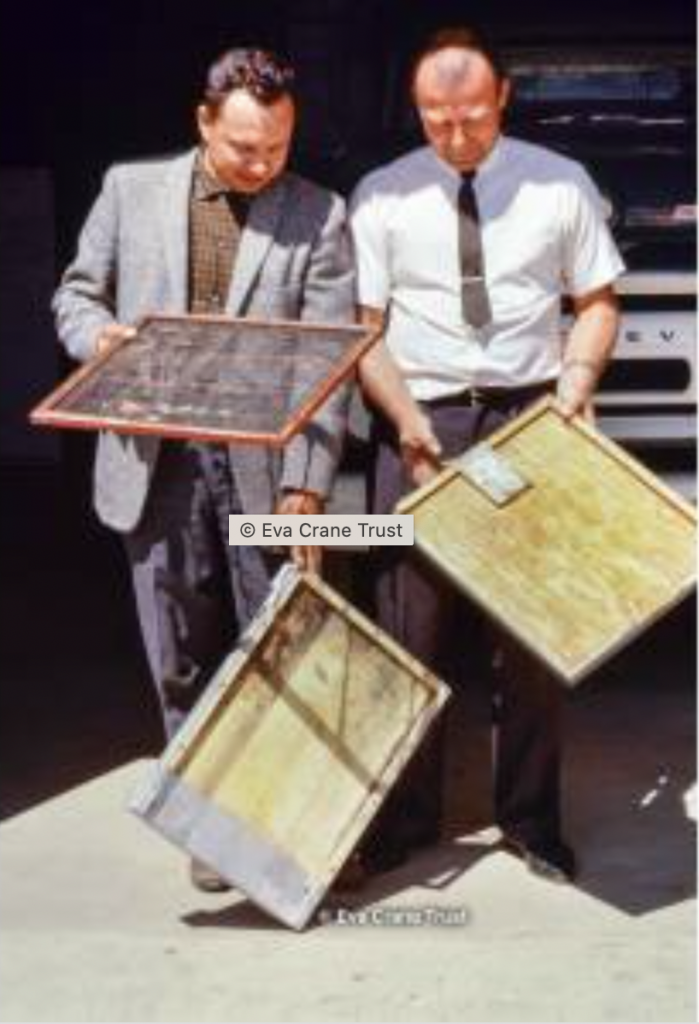

Like E.W. Alexanderviii, Peer was an inveterate inventor. Here he is (Figure 1) with two honey gates no doubt fabricated to manage his giant honey harvests.

Figure 1 Peer with two honey gate designs. Image ECT-0375

Writing about the exigencies of controlling bee shed fires, Mikshaix also reports:

A beekeeping colleague in Nipawin, Saskatchewan,Dr Don Peer, years ago built a very long narrow honey shop: ‘Just in case of a fire’, he told me.

And writing about bee losses, Miksha writes of Peerx:

I am aware that winter losses for most North American beekeepers are higher than keepers can afford. It used to be expected that 15% of colonies would die each winter, according to statements made in the 1970s by commercial beekeeper and research scientist Dr Don Peer. Losses of 30% are frightening. Especially when that is an average. It means some beekeepers lost a whole lot more. For some operators, there is no recovery. Since those 30% averages have been sustained in most parts of the USA, research is conducted to try to find the cause. Everything from varroa mites to neonicotinoids to genetic weaknesses have been implicated.

Peer describesxi how he learnt to overwinter bees in Saskatchewan winters, seasons that can plummet to -400 C. Peer’s was an era where beekeepers killed their bees using hydrogen cyanide gas starting afresh with package bees each April.

In summarising Peer’s method Walker reports:

In September the colony is fed, a bottom entrance reducer is put in position with a hole over the top entrance of the hive. In October, pre-cut fibreglass insulation is packed around a group of four hives, and the whole is covered with black building paper. There is a gap in the insulation over each top entrance hole, and this is finally covered with a piece of plywood in which there is a 10×1.9 cm slot allowing moisture to escape from the hive. Another piece of plywood tied to the top of the hive serves as a roof. Of colonies overwintered this way, about 90% have survived, and in the following year their honey production has been 50-125% higher than in control packages.

Clearly overwintering bees successfully was becoming a strategy superior of restarting hives each spring with package bees.

On the character of Peer, Allen Dick writes in a late report (2003)xii:

I recall, some thirty three years ago, when I was first about to set up beekeeping in Alberta, writing Dr Peer asking advice on my (somewhat simplistic and idealistic) plans. He wrote back a long and very thoughtful letter explaining where I would go wrong, and how I could make my plan work.

I’ve never forgotten that, and if there is one experience that has caused me to want to share what I have learned in beekeeping – once I got to the point where I had something worth sharing – it is that example of neighborliness to a (stupid?) unknown kid in Alberta by Dr Peer, whom I had never met at that time.

I did meet him later on a number of occasions, and know he was a man of strong opinions, and some of his opinions I could not support. I guess I learned something from that too. Nonetheless, I always did respect him.

Earlier Eva Crane recalls her encounterxiii with Peer (Figure 2) in rather more detail:

I found Nipawin a stimulating place mentally: Mr Hamilton was very knowledgeable, and almost next door lived Dr DF Peer, whom I had last met in 1953 in Madison, doing research work under Dr CL Farrar—whose methods of management he both practises and preaches. Don Peer left his career in bee research several years ago, because he could get a much higher income by producing honey. More than almost anyone I met, he seemed to have thought out the biological and economic implications of colony development and honey production in the near-optimum conditions in parts of the Prairie Provinces.

… Don Peer uses two-queen colonies on Dr Farrar’s systemxiv. He gets 2-lb. packages about 23rd April, and uses two per hive, the division board between them being later replaced by a queen excluder. By 23rd June or so the 16 000 bees in the two packages have produced 70 000 or 80 000; by July there are 90 000 or 100 000 in each hive. A thousand or more hives, in apiaries of 25-35, are spread over an area perhaps 50 x 30 miles [80 x 50 km], parts of which are also used by other beekeepers. During my visit Dr Peer gave a party for seed producers and local officials, to discuss pollination problems, and to show them round his honey house; this was a model plant, which made a great impression on all the visitors. I was distressed to learn that, although it is only just completed, it will shortly be destroyed when a dam is built across the river.

|  |

| a | b |

Figure 2 Don Peer and two-queen hives:

(a) with Bill Hamilton [Image ECT-0375]; and

(b) one of Don’s many scattered two-queen apiaries [Image ECT -0374]

Don also published on other facets of managing package bees, both on their installation and in control of swarmingxv.

Steve Taber, a renowned north American queen breeder and researcher at the US Department of Agriculture Honey Bee Breeding, Genetics, and Physiology Research facility at Baton Rouge facility in Louisiana came up with this anecdote about Peer:

Some years ago an old acquaintance of mine came out with the idea of requeening a hive with the old queen still there. His name was Don Peer, who lived in what he said was ‘bee paradise’ in Nipawin, Saskatchewan, Canada. And, for many of you who don’t know where that is, it is north of Montana and North Dakota. I have been in the southern part of Saskatchewan, but never that far north.

This, of course is now standard requeening practice but it relies on supersedure of the old queen by a new queen well established on top of the existing brood nest with that old queen. But the notion was certainly novel at the time.

In 1979, a Frenchman Yves Garezmet met Don Peer subsequently working at Peer’s Bee Ranch (Figure 3) from May 1983 to October 1989 while he was establishing his own bee business. In his blogxvii, Ives records:

…the previous professor of entomology from Madison, Wisconsin, owned and operated 1200 colonies in Nipawin, Saskatchewan. Don offered Yves a job and became his mentor. Just like Don many years before, Yves fell in love with the beautiful hills and prairies surrounding Nipawin. He found an old farm house to rent, and while working for Don during the week, he would manage his own bees in the evenings and week-ends: these were very busy summers for a dad and a mom with little children.

…Upon Don’s retirement in 1995, Yves was able to acquire 1000 more hives from Don’s outfit, he also bought the quarter of land on which he lived.

|  |

Figure 3 Peer’s famous bee acreages Images ECT -0371 and ECT -0372

Peer was also involved in early seasonal studies of infestation of hives by acarine mitexviii, an era that preceded the ravages of varroa mite:

…package bees infested with A. woodi were installed in two apiaries in early May. Average infestation was initially 27% and it rose to 48% by early June. After decreasing to 30% in early August, it rose to 42% by mid-October. In colonies started with uninfested packages the October level was 7%. In infested nuclei, the infestation increased steadily from 3% in mid-March to 33% in mid-October. As in the 1986 study, brood production was significantly lower in infested colonies than in controls (except on two dates), and this affected the size of the resulting adult population. Preliminary trials with menthol reduced the mite infestation, but the menthol evaporated rather slowly because of low ambient temperatures.

Peer was also an exceptionally keen observer of the changing fortunes of beekeepersxix in northern Canada:

Before the 1970s the honey plant we call canola didn’t exist. Canola – named for Canada oil – was bred from lesser plants that once yielded a lethal seed. Farmers planted a little of canola’s poisonous ancestor – especially during World War II – to make lubricating oil for prairie tractors. Today 20 million acres of canola are planted in Western Canada. The bright yellow flowers attract bees, but the honey from canola crystalizes within days. That’s why beekeepers started having problems up in northern Saskatchewan. Beekeepers, of course, learnt to extract early before the honey hardened in their supers. They paid more attention to their bees and honey production soared.

Don Peer, like most exemplary apiarists has disappeared into the annals of beekeeping. That said he has taught us a lot about innovative beekeeping practice.

In compiling this article, I’ve corresponded with that font of Canadian beekeeping practice, Ron Miksha, from whom we learn so much about Don. In his book Bad Beekeepingxx Ron recounts a parallel universe where he ended up leaving a family steeped in beekeeping in Florida to become a Canadian citizen and beekeeper and harvest, like Don Peer, astounding amounts of prairie honey. That was until a mega drought of the 1980s put him out of business.

Ron’s recounts a honey packer who kept cards describing the proclivities of the beekeepers he did business with. Don Peer had asked:

Can I see the note card you have on me?

When Don read the card about himself, he was surprised to see it simply said:

Doesn’t need money.

Readings

iMikska, R. (August 2018). How to predict the honey flow. Bad Beekeeping Blog. https://badbeekeepingblog.com/2018/08/02/how-to-predict-the-honey-flow/

iiCrane, E. (2003). Making a Beeline: My journeys in sixty countries 1949-2000. International Bee Research Association.

iiiMiksha, R. (June 2019). Remembering Eva Crane: Beekeeper and physicist. Bad Beekeeping Blog. https://badbeekeepingblog.com/2019/06/12/remembering-eva-crane-beekeeper-and-physicist/

ivMiksha, R. (August 2001). Honey combing – Selling your gold. Bad Beekeeping Blog. http://www.badbeekeeping.com/chc_04.htm

vPeer, D.F. (1955). The foraging range of the honey bee, PhD Thesis, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI. Part I: The foraging range of the honeybee; Part II: The mating-range of the honeybee, 102pp.

Peer, D.F. and Farrar, C.L. (1956). Mating range of the honey bee. Journal of Economic Entomology 49(2):254-256. doi.org/10.1093/jee/49.2.254

Peer, D.F. (1956). Multiple mating of queen honey bees. Journal of Economic Entomology 49(6):741–743. doi:10.1093/jee/49.6.741

Peer D.F. (1957). Further studies on the mating range of the honey bee, Apis mellifera L. Canadian Entomologist 89(3) 108-110.

viTarpy, D.R., Delaney, D.A., Seeley, T.D. and Nieh, J.C. (2015). Mating frequencies of honey bee queens (Apis mellifera L.) in a population of feral colonies in the northeastern United States. PLOS ONE 10(3):e0118734. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0118734

Tarpy, D.R., Nielsen, R., and Nielsen, D.I. (2004). A scientific note on the revised estimates of effective paternity frequency in Apis. Insectes Sociaux 51(2):203-204. doi.org/10.1007/s00040-004-0734-4

viiPeer, D.F. (1957). Further studies on the mating range of the honey bee, Apis mellifera L. The Canadian Entomologist 89(3):108-110.

viiiRoot, H.H. (ed) (1910). Alexander’s writings on practical bee culture, third edition, 124pp. A.I. Root Company, Medina, Ohio. https://ia800206.us.archive.org/18/items/cu31924003065244/ cu31924003065244.pdf

ixMikska, R. (June 2013). Fire in the shop. Bad Beekeeping Blog. https://badbeekeepingblog.com/2013/06/03/fire-in-the-shop/

xMikska, R. (August 2013). Time to say goodbye – or maybe not. Bad Beekeeping Blog. https://badbeekeepingblog.com/2013/08/09/time-to-say/

xiPeer, D.F. (1978). A warm method of wintering honey bee colonies outdoors in cold regions. Canadian Beekeeping 7(3):33, 36. Abstract by Richard Jones (2005). Bibliography of Commonwealth Apiculture (Google Books). https://books.google.com.au/books?id=sOBiT384y3YC&pg=PA57&lpg=PA57&dq=Peer,+D.F.+(1978).

xiiDick, A. (February 2003). Honeybeeworld.com A Beekeeper’s Diary. https://www.honeybeeworld.com/diary/2003/diary020103.htm

xiiiCrane, E. (1966). Canadian bee journey. Bee World 41:55-65, 132-148. Reprinted from https://www.evacranetrust.org/uploads/document/a6e5fe111233c705b26c4a35d3f0022a54d15d9d.pdf

xivPeer, D.F. (1965). Two-queen management with package bees. Bee-Lines 21:3-7. Cited by Crane (1966) loc. cit.

Peer, D.F. (1969). Two-queen management with package colonies (Apis mellifera). American Bee Journal 109(3):88-89. Cited by Valle, A.G.G., Guzmán-Novoa, E., Benítez, A.C. and Rubio, J.A.Z. (2004). The effect of using two bee (Apis mellifera L.) queens on colony population, honey production, and profitability in the Mexican high plateau. Téc Pecu Méx 42(3):361-377. http://cienciaspecuarias.inifap.gob.mx/index.php/Pecuarias/article/viewFile/1404/1399

xvPeer, D.F. (1969). Package bees – Installation and management. American Bee Journal 109(2):50-51.

Peer D.F. (1969). Swarming, causes and control with package bees. American Bee Journal 109(4):139. Peer, D.F. (1972). Swarming: Causes and control with package bees. Canadian Department of Agriculture.]

xviTaber, S. (2002). Requeen your bees without first removing the old queen. American Bee Journal 142(4):275-276. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/297976630_Requeen_your_bees_without_first_removing_the_old_queen

xviiGarez, I. (2022). Yves Garez Honey Inc. https://ca.linkedin.com/in/yves-garez-9b1b93107

xviiiGruszka, J., Peer, D. and Tremblay, A. (1990). The impact of Acarapis woodi on the development of package bee colonies. Beelines 89:9-24. https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/19910230771

Peer, D., Gruszka, J. and Tremblay, A. (1987). Preliminary observations on the impact of Acarapis woodi on the development of package bee colonies. Saskatchewan Beekeepers Association 81:1-8. https://scholar.google.com.au/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Peer%2C+D.%2C+Gruszka%2C+J.+and+Tremblay

xixMiksha, R. (2016). How to keep honey from granulating before extracting. American Bee Journal 156(8):899-901. https://bluetoad.com/publication/?i=318073&article_id=2528241&view=articleBrowser&ver=html5

Downloadable as pdf at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320233431

xxMiksha, R. (2004). Honey Crop, p.70: Bad Beekeeping, 307pp. Trafford Publishing, Victoria, B.C., Canada.