Alan Wade, Jenny Robinson and Peter Robinson

In May 1967 Sergeant Pepper’s lonely hearts club band hit the number one spot on the Top Forty charts: Beatlemania was rampanti. The 2002 arrival of small hive beetle [SHB] (Aethina tumida) from sub Saharan Africa saw the beginnings of an Australian beetle mania. By then SHB was already very well established in the southern United States arriving there as early as late 1996ii. And as for Beatles, With a Little Help from My Friends rings sour when a bee hive takes in unfriendly beetles.

Now twenty years on southeastern Australia has experienced consecutive uncharacteristically wet and humid summers. Already the bane of the coastal, and northern coastal zones, anecdotal reports indicate SHB is now creating significant problems for beekeepers on the Southern Tablelands. Former club president Dermot Asls Sha’Non, a noted collector of nuisance hives around Canberra, remarked:

‘I’ve never seen the numbers of SHB that I’ve been seeing recently before this. I’ve lost a few recovering cut-out colonies to them. It hasn’t happened in previous seasons.’

To date most of the world remains free of the sub-Saharan Large African Hive Beetle [LAHB], rather two beetles, Oplostomus fuligineus and Oplostomus haroldi and many colder climes remain unaffected by SHB. So what do we know about SHB and how can we best manage it and what is the impending threat of LAHB.

A couple of years ago the former editor of The Australasian Beekeeper Des Cannon was at a bee forum in New Zealand. He was there to give a talk on the hazards presented by small hive beetle, when a South African speaker at the forum, Mike Allsopp, got up to say:

‘You think you have a problem with SHB.’

‘You haven’t encountered the large African hive beetle (LAHB). It is like a tractor hauling a harvester mowing combs in your hive.’

Mike has been joined by our very own Ben Oldroyd in surveying the existential threat of this mega beetle to Australian beekeeping and to crops reliant on bee pollination of which more anon. So add beetle surveillance to your disease check list and be aware that moths can take a similar toll.

Small Hive Beetle

Almost 6000 SHB larvae can be raised on a single frame of brood. Larvae mature in moist soil generally close to – but anywhere up to 100 m away from – the hive. Emerging adults can fly ten kilometres, again generally less, guided largely by honey bee alarm pheromone. Here they infest new hives or augment the populations of beetles already present.

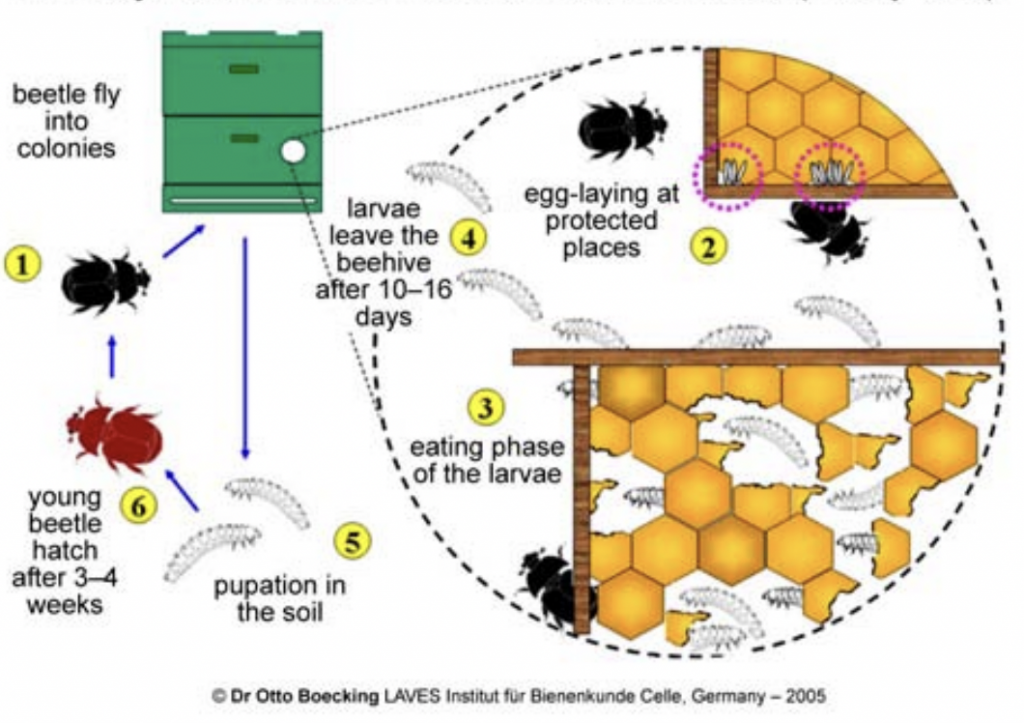

Nicholas Annand from the NSW Department of Primary Industries describes the key options for managing SHB reproducing an excellent diagram outlining beetle life cycle (Figure 1)iii:

Unlike wax moth larvae which produce webbing (the damage left is dry), SHB larvae chew through combs, causing the honey to ferment, resulting in ‘sliming’ of the combs…

SHB are capable of prolific multiplication. Under laboratory conditions 80 SHB can become more than 36,000 adult SHB by day 63.

Figure 1 Life cycle of small hive beetle

Photo: Otto Boecking

Entrapment

While weak hives are certainly more susceptible to SHB takeover, in the normal course of events and with Canberra’s usual hot dry summer, the beetles have rarely gained a foothold.

A good case for intercepting flying beetles by any means possible is to employ fruit-fly style lure trapsiv located in the general vicinity of beehives. A more targeted approach is to lay a chux wipe on top of frames. However beetles trapped in the fiber also ensnare some bees. A superior strategy – one currently used by Des Cannon – is to place a carpet square under the mesh screen bottom board where it serves also to monitor beetle numbers.

Many beekeepers we know ignore the occasional, say up to half a dozen or so, beetles they find squishing the few that appear on top bars before they scurry away to the comb matrix. Others opt for fairly passive control relying on look-alike mini stormwater-gully style traps (Figure 2) that are inexpensive and that you can purchase in bulk on-line. You spoon in diatomaceous earth (a swimming pool filter medium available from pool shops and some stock and station agents) or simply pour in a tablespoon of cooking oil. Workers chase beetles into the traps where their spiracles clog up and they die.

A more effective cassette-style ‘Apithor’ trap (containing the insecticide fipronil) works well and is safe to use provided it is handled wellv. Place the trap smooth side down – to prevent harbourage of beetles and wax moths under trap and mark date of placement on trap using a marker pen. While the manufacturers claim an effective three month period, one probably suited to warm moist coastal apiary locales, Doug Somerville from the NSW Department of Primary Industries provided informal advice that they be replaced each spring at least for the NSW Southern Highland climate.

More innovative approaches such as that just reported by Neil Richievi, involving under-floor traps, avoid the use of chemicals but require regular maintenance.

In our experience this annual trap replacement works well. Beetles rarely ever appear and by late autumn the weather is too cold for beetles to migrate and to become established.

Figure 2 SHB trap inserted between frame top bars

The gooey mess produced by beetles is toxic to humans so handing slimed combs and gear (Figure 3) should be conducted with gloves and a protective mask. As Rod Bourkevii points out, cleaning up hives overtaken by the beetle is not much fun. Take Rod’s advice by intervening early by euthanising bees, then opting for a total clean out whenever beetle larvae present themselves en masse. We can attest to this after finding a hive taken over by the beetle co-infected with American Foul Brood. The seething mass of larvae and their spilling out onto un-diggable rocky soil and having to saturate the surrounds with a registered insecticide was a gargantuan struggle.

Ooey gooey was a worm

And a mighty worm was he

He sat upon a railroad track

And a train he did not see

Ooey Gooey!

Traditional Scout ditty

Since the life cycle, eggs to adult, can be as little as 4-6 weeks, there may be as many as six generations per year under favourable conditions. Beetles can also breed on stored hive combs and hive debris around hives and in bee sheds so, as with wax moths, it is best to extract honey quickly and to avoid leaving hive scrapings around the apiary. Little wonder that weak hives can easily fall prey to SHB and that whole apiaries can be at risk if good hygiene is not maintained. Requeening hives with strains that produce hygienic behaviour workers, keeping hives strong and removing excessive amounts of gear are all strategies that limit the risk of severe colony damage.

Figure 3 (a) Tell-tale slime očzing from a small hive beetle infected hive

Figure 3 (b) Beetle larvae spoilage of stored honey

Photos: Peter and Jenny Robinson

But what measures can you take if you have failed to take preventive action and find patches of brood overrun by a seething mass of beetle larvae? We (Peter and Jenny) found a single hive that had become queenless – probably weakened in the process – that already had several slimed-out frames. What to do?

First we considered trying to requeen the unit after replacing the damaged frames proposing to achieve this by inserting several frames of sealed brood along with a spare queen at hand. This may well have worked but we had six other healthy hives and there was a small risk that disease may have been a factor in the colony’s dwindling. In any case there was the more tangible risk that small hive beetle eggs were present in large numbers on sound frames and anyway the queenless bees were exceptionally cranky. This is something that visitor Alan discovered when, to his great discomfort, he turned up suit-less to help appraise the situation.

With discretion being the better path than valour, Jenny and Peter euthanised their likely old bees by shaking them into a tub of water laced with a squirt of dishwashing detergent. Any few bees that escaped simply joined other healthy hives. The remaining ‘good frames’ were given the freezer treatment.

Such recovery plans are not hard to implement. In the days when Alan was starting up in beekeeping and AFB was rare his Tharwa out apiary was diagnosed with possible AFB and was strictly quarantined. As it turned out the hives were found to be infected with European Foul Brood, a disease exacerbated by the stress of spring brood raising. The bees were treated with oxytetracycline (Terramycin) laced sugar water.

Surprisingly EFB outbreaks now appear to be rare at least around Canberra. At the time the bees were given a good spell to recover being careful not to harvest honey till the antibiotic degraded and left no residue.

The American practice of regular antibiotic dosing to control AFB has been a disaster: it is illegal in Australia. According to Randy Oliver from Scientific Beekeeping, the use of miticides to control Varroa has been counterproductive: Randy culls hives collapsing from – or overrun by – mites and uses the natural organic oxalic acid to knock down mite numbers in other hives. This treatment is vital late in the season when mite numbers build up as the population naturally declines.

His thesis is that the tandem mite and virus duo hides behind the mite treatment to the advantage of the virus. Anyway, hive mortality is high wherever Varroa is endemic and only breeding for mite resistance – something that Thomas Seeley has discovered with wild colonies – is likely to be the most viable proposition. In-hive chemical treatment has a serious downside: honey and wax inevitably carry traces of the treating miticide.

There is no registered hive treatment of SHB so put that can of fly spray away!

Beetle behaviour

Ellis and Ellis at the University of Florida have produced a contemporary account of small hive beetle behaviour:viii

Investigators have shown that small hive beetles fly before or just after dusk and odors from adult bees and various hive products (honey, pollen) are attractive to flying small hive beetles. Some investigators have suggested that small hive beetles also may find host colonies by detecting the honey bee alarm pheromone. Additionally, small hive beetles carry a yeast (Kodamaea ohmeri) on their bodies that produces a compound very similar to honey bee alarm pheromone when deposited on pollen reserves in the hive.’

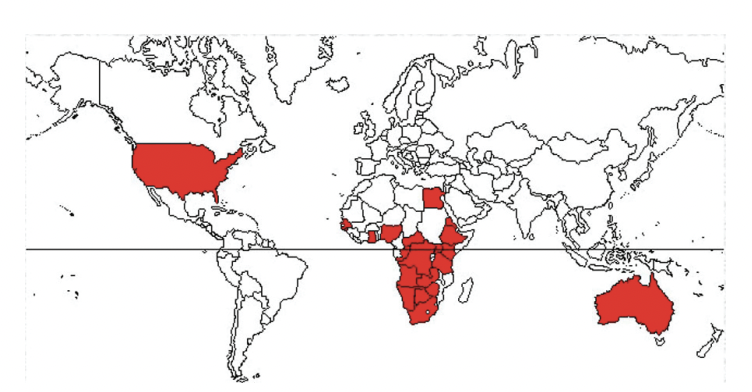

These workers outline their spread and their then 2010 distribution (Figure 4) and refer back to studies by Neumann and Elzenix describing the biology of SHB and their much earlier spread in Africa where they appear to be a minor pest.

Figure 4 Distribution of small hive beetle as at 2010

Large African Hive Beetle

Two species of ALHB are native sub-Saharan Africa. Oldroyd and Allsopp have made some keen observations on the beetles in their African habitat. Based on a Kenyan study and their observations in South Africa and Botswana, it appears likely that of the two species Oplostomus haroldi has a preference for wetter coastal areas and that Oplostomus fuligineus is more common in dryer grazing land where dung is abundant.

The measures required to exclude this beetle monstrosity include providing a beetle proof hive entrance (Figure 5), and a perforated hive bottom board to allow mature larvae to migrate and pupate in a dung-filled subterranean trap. The authors also survey food preferences for ALHB signalling a low preference for sand, cow dung, local soil and straw and a strong preference for horse dung along with a strong dietary preference for brood comb, a slightly lower preference for pollen, a much reduced preference for comb honey and a low preference for fruit. Destructive large hive beetles attack the colony engine, brood areas that colonies depend on to replace and maintain worker honey bee populations.

Adult ALHB prey on bee brood, whereas larvae and pupae live in dungx. Giant hive beetle poses an existential threat to all beekeepers worldwide: these behemoths – no they are not moths – pose a danger also drawn attention to by BeeAwarexi.

Figure 5 African large hive beetle at a hive entrance

Photo: Ben Oldroyd

It you are worried about the prospective damage that would be inflicted on honey bees by a failure of quarantine to keep this beetle out of Australia, we ask you to support Plant Health Australia – by keeping a sharp eye out for this marauder – in its efforts to keep Varroa and Tropilaelaps mites out of our great brown land and to make sure that such such wreckers as African Large Hive Beetle never make it to our shores. To get the full story on African Large Hive Beetle, simply click at https://www.agrifutures.com.au/wp-content/uploads/publications/16-054.pdf

Beetles in other environments

Do hive beetles just affect honey bees? SHB has been reported to successfully cycle on fruit but reports of such damage are sparse and it appears to be principally only a problem for European honey colonies kept in warm moist zones. There SHB wipes out feral colonies. And stingless bees, while not subject to wax moth predation, appear to have good defences against SHBxi.

Small hive beetle, Aethina tumida Murray, is a parasite of social bee colonies and has become an invasive species, raising concern of the potential threat to native pollinators in its new ranges. Here, we report the defensive behavior strategies used by workers of the Australian stingless bee, Austroplebeia australis Friese, against the small hive beetle. A non-destructive method was used to observe in-hive behavior and interactions between bees and different life stages of small hive beetle (egg, larva, and adult). A number of different individual and group defensive behaviors were recorded. Up to 97% of small hive beetle eggs were destroyed within 90 min of introduction, with a significant increase in temporal rate of destruction between the first and subsequent introductions. A similar result was recorded for 3-day-old small hive beetle larvae, with an increased removal rate from 62.5 to 92.5% between the first and second introductions. Of 32 adult beetles introduced directly into the 4 colonies, 59% were ejected, with the remainder being entombed alive in hives within 6 h. Efficiency of ejection also significantly increased between the first and third introductions. Our observations suggest that A. australis colonies, despite no previous exposure to this exotic parasite, have well developed hive defences that are likely to minimize entry and survival of small hive beetles.

A concluding note

We, the authors, will have abandoned beekeeping by the time mites and large beetles make beekeeping in Australia a near impossibility. We conclude on a positive note:

Of six healthy colonies in Peter and Jenny’s hives, one other appeared to have become queenless and soon succumbed to SHB. Peter and Jenny have upgraded their integrated pest management system, using Apithor hive beetle traps installed on the floor of each hive and adding disposable beetle traps with diatomaceous earth on the bars of the top supers.

Readings

iSgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sgt._Pepper%27s_Lonely_Hearts_Club_Band

iiNeumann, P. and Elzen, P.J. (2004). The biology of the small hive beetle (Aethina tumida, Coleoptera: Nitidulidae): Gaps in our knowledge of an invasive species. Apidologie 35(3):229–247. doi:10.1051/apido:2004010

Müerrie, T. and Neumann, P. (2004). Mass production of small hive beetle (Aethina tumida, Coleoptera: Nitidulidae). Journal of Apicultural Research 43(3):144-145. doi: 10.1080/00218839.2004.11101125

iiiAnnand, N. (March 2008). Small hive beetle management options. New South Wales Department of Primary Industry PrimeFacts, 7pp. https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/220240/small-hive-beetle-management-options.pdf

ivBowman, P. (24 April 2014). Catching small hive beetle: How to prepare and deploy lantern traps. AgriFutures video: https://youtu.be/yhumk5slzxu

vLevot, G. (2012). Commercialisation of the small hive beetle harbourage device. Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation publication no. 11/122, 46pp. https://www.agrifutures.com.au/wp-content/uploads/publications/11-122.pdf

viRitchie, N. (2022). Deep hive bases and trays for controlling small hive beetle. The Australasian Beekeeper 121(10):24-25.

viiBurke, R. (2022). Cleaning up small hive beetle slime-outs. The Australasian Beekeeper 123(8):45-47.

viiiEllis, J.D. and Ellis, A. (2019). Small hive beetle, Aethina tumida Murray (Insecta: Coleoptera: Nitidulidae), 5pp. University of Florida IFAS Extension Publication #EENY-474. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdf/IN/IN85400.pdf https://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/misc/bees/small_hive_beetle.htm University of Florida

ixNeumann, and Elzen (2004) loc. cit.

xOldroyd B.P. and Allsopp M.H. (2017a). Risk assessment for large African hive beetle. Research report, Rural Research and Development Corporation, Canberra publication no. 16/054. https://agrifutures.com.au/wp-content/uploads/publications/16-054.pdf

Oldroyd, B.P. and Allsopp, M.H. (2017b). Risk assessment for large African hive beetles (Oplostomus spp.) – a review. Apidologie 48(4):495-503. doi:10.1007/s13592-017-0493-7 Overviewed by Diedrick and Jack, C. (July 2020). University of Florida project No. Eeny-763,

Large African hive beetle Oplostomus fuligineus (Olivier) (Insecta: Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IN1309

This publication updates an earlier review entitled Oldroyd, B. and Allsopp, M. (2006) Risk assessment for large African hive beetle. Rural Industries R&D Corporation, 8pp. https://www.agrifutures.com.au/wp-content/uploads/publications/16-054.pdf

xiBeeAware at Plant Health Australia. Large African hive beetle now high priority pest. https://beeaware.org.au/archive-news/large-african-hive-beetle-now-high-priority-pest/

xiiHalcroft, M., Spooner-Hart, R. and Neumann, P. (2011). Behavioral defense strategies of the stingless bee, Austroplebeia australis, against the small hive beetle, Aethina tumida. Insectes Sociaux 58(2):245–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00040-010-0142-x