Alan Wade

All together altogether

We often take for granted that bees work cooperatively and then it would seem of their own volition? We would be quite surprised were we hive a swarm only to discover they failed to stay as a group and get on with the serious business of making honey.

In this ‘beyond-social cooperation’ scenario, so-called eusociality, the altruistic worker bees stay at home to provision their parents’ offspring, give up the opportunity to reproduce themselves and even stay faithful to their mother when she departs with a swarm. Understanding their community dynamic is instructive, if only to give us advance warning of global disruptors such as Varroa and Tropilaelaps and the viruses they carry. It is sobering to realise that, before jumping ship to our bees, these parasites evolved with their also socially sophisticated cousins, the Asian Honey Bee and the Giant Honey Bee.

The introduction of the Western Honey Bee from the Old World is the reason we have a beekeeping club and that the world at large is provided with scuds of honey and their beneficial pollinating efforts to enhance our crops. As collateral they affect the way our forests are structured, they compete with other insects and birds and they are an unwitting weed promoter.

But bees are the just the tip or, rather, right at the top of the social iceberg. Out there, there are a plethora of social lookalikes both amongst other bees and also the ants and the wasps. The evolution of social castes, where offspring are partly or entirely subordinate to the sexually dominant parents is an extremely rare event. So much so that the origin of true social behaviour has been tracked back to just nine separate ancestors amongst the wasp-bee-ant community, seventeen amongst thrips and to only eight other lineages in the remainder of the animal kingdom.

The common supposition is that social behaviour arose from the condition where food was plentiful and where getting together meant that the group could fend off predators. In other words the group could make a better fist of surviving than going it alone. But this was not enough. Like a bunch of precocious children, the group had to learn to share resources and to help with the housework. The chances of this stay at home, ‘never ask for a date’ strategy working were so remote that by and large insects have retained the very successful strategy of ‘one girl meets one boy’ to pass on their story to the next generation. Most insects are solitary.

However once rare sociality was initiated, the tide turned. To mix two escape metaphors either the ‘cat got out of the bag’ and ‘the horse had bolted’. Amongst the most socially advanced insects, the division of labour finally evolved to the point where the separate caste of worker (and in the case of some ants also soldier) is sterile or at least functionally asexual. As Wilson and Hölldobler have put it, workers reached a point of no return: they could no longer pass on their genes. The workers, albeit closely related to their parents, started to care cooperatively for the young as robots and became a non reproductive (or at least less-reproductive) caste incapable of founding new colonies.

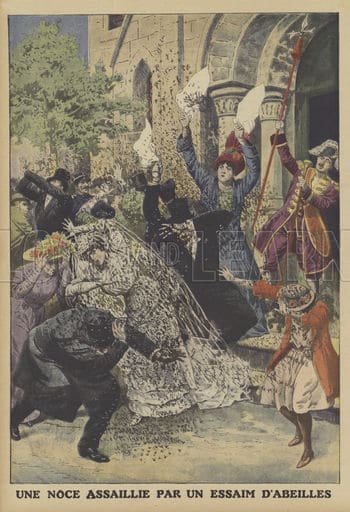

A social occasion, a 1912 wedding interrupted by bees that had long learnt how to organise their own nuptials

Source: Look and Learn History Picture Library: https://www.lookandlearn.com/history-images/M512371/A-wedding-assailed-by-a-swarm-of-bees?t=2&q=interruption&n=9

A quick rain check

Social ants, social bees and social wasps dominate the global invertebrate community both ecologically and in terms of other simple metrics such as total biomass. Once started, the evolutionary pressures resulted in the development of menagerie of social lifestyles and an explosion in the number of their species. Collectively they out-compete their much much more diverse and numerous solitary relatives.

The ants, bees and wasps together

Apart from one beetle, a bevvy of thrips, aphids and termites, and a few snapping shrimps, not to mention a couple of African Mole Rats where the youngsters all stay home to look after their siblings, the really advanced social animals all belong to a single insect suborder of the Hymenoptera, the Apocrita. These are the ‘lacey-winged, narrow waisted, ovipositor-specialised’ insects made up of ants, wasps and bees. While ants are all social in varying measure, most bees and wasps are solitary. Social species are conspicuous by dint of their sheer numbers and gregarious habit.

The most advanced social tribe, the honey bees (Apini) is unusual in that it has a single genus, Apis, while the orchid bees of South America (Euglossini) are mainly solitary and only a few species are semi-social.

As noted previously, eusociality has evolved nine times amongst Hymenoptera. Here we can go further and look to the breakdown: three times amongst halictid bees, once amongst the pollen basket (corbiculate) bees: the honey bees, the stingless bees, the primitively eusocial bumble bees and the now solitary or weakly social orchid bees, three times amongst the wasps and only once amongst the ants.

Social bee, wasp and ant progenitors

|

Social Taxa |

Progenitors |

Origin date |

Number of queen mates |

Number of social species |

|

Halictid bees (Halictidae) sweat bees |

3 |

15-28 |

Usually 1 |

140 + 217 + 544 |

|

Allodapine bees (Allodapinae) |

1 |

41-65 |

1? |

? |

|

Corbiculate bees (Apidae) |

1 |

78-95 Apini (56-61) Bombini (28-35) Euglossini (65) |

8-44 in Apis |

1000 |

|

Sphecid wasps (Sphecidae) |

1 |

~140 |

1 |

1 |

|

Stenogastrine wasps (Stenogastrinae) |

1 |

~80 |

1 |

50 |

|

Polistine and vespine wasps (Vespidae) |

1 |

~80 |

Usually 1 |

860 |

|

Ants (Formicidae) |

1 |

115-135 |

1 |

12,000 |

Sources: Simplified after Hughes, Oldroyd et al. (2008), Cardinal and Danforth (2011) and others

In the next Bee Buzz Box we shall look at how these insects are related to one another and reflect on some common Australian social ant, wasp and bee taxa.

Readings

Hughes, W.O.H., Oldroyd, B.P., Beekman, M. and Ratnieks, F.L.W. (2008). Ancestral monogamy shows kin selection is key to the evolution of eusociality. Science 320: 1213. DOI: 10.1126/science.1156108 or at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18511689

Wilson, E.O. and Hölldobler, B. (2005). Eusociality: origin and consequences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102(38):3367–13371. http://www.pnas.org/content/pnas/102/38/13367.full.pdf

Cardinal, S. and Danforth, B.N. (2011). The antiquity and evolutionary history of social behavior in bees. Plos One 6(6):e21086 http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0021086

Be the first to comment