Alan Wade

In the 1950s an eminent group of American apiarists collaborated to present a coherent approach to spring hive management. They realised that the processes of honey bee population buildup, swarm preparation and queen replacement were essentially inseparable. They argued that these elements of bee survival should be viewed collectively as the natural processes of colonies making provision to requeen themselves, to reproduce and to build stores for periods of dearth.

To replicate the natural inclinations of honey bee colonies they asked themselves how they could devise simple plans to build bees continuously while at the same time requeen their hives. They wanted to copy what bees do well and had practised for millions of years. And to avoid swarming, they played a confidence trick on the bees: they divided the population at a critical juncture to imitate swarming and either supplied a new queen or got the bees to raise one themselves without curtailing the full laying capacity of the old queen.

The Killions of comb honey production fame conjectured that swarming was not the problem it is always made out to be, rather an opportunity to work with and harness the natural reproductive instincts of bees.

So what did these American beekeepers actually practise? Some of their schemes were adaptations of the Demaree swarm control plan where they also got colonies to raise or accept new queens. The new queen would invigorate the colony, head off queen failure, suppress the swarming instinct, and get bees to focus on brood nest rebuilding and on harvesting and storing honey and pollen.

A recurrent feature of their plans was the establishment of a new queen without having to resort to finding and removing the old colony queen. While old, diseased and patently failing queens heading struggling colonies were found and quickly despatched, every effort was made to continue to employ the laying capacity of any well-functioning colony queen that was at least until the new queen were well established and had her own retinue of bees.

A proactive, not a preventive strategy

Ready access to a bank of new season queens is good insurance against imminent queen failure, in practice either a supply of caged queens, ordered at the close of the last season to ensure availability, or cells raised in a strong colonies early in the season under ideal conditions.

However spare queens, lying idly in offset nucleus colonies, do little for apiary productivity unless their brood and stores are routinely raided to strengthen colonies. Extra queens put directly into service not only boost colony numbers but also supply an additional titre of queen pheromone. These queens, working the on either side of a double screen or nucleus board, were used subsequently to replace old and failing queens or double to supersede colony queens as soon as the services of the old hive queens were no longer needed.

Put more bluntly there was a ready awareness that honey bee colony queens wear out, just as do drones and workers: a second queen could be used to work in concert with a still well-functioning queen to fortify the colony and, in due course, replace her.

You might ask what these innovative beekeepers had in common in terms of their approach to using two queens laying in parallel? The answer is not a great deal. However they all recognised the inestimable value of having a second laying queen present instead of the standard new queen replaces old queen routine. Many like Clayton Farrar and Winston Dunham went much further. They were experienced two-queen hive aficionados and could reckon on their adjudging the relative merits of a newly grafted in queen versus that of the old parent colony queen working together in the same hivei.

The goal here, however, was not to run hives with two queens but to run conventional single-queen hives at full tilt. Their shared trick was to employ a second laying queen to smooth queen succession and to avoid any interruption to the brood cycle during the period of buildup. As importantly they realised the serious downside of maintaining a second queen for any longer than were absolutely necessary. Two laying queens at the end of the main honey flow would equate to too much brood and an over supply of hungry bees, a common enough mistake made in two-queen hive operation.

In most of their schemes they introduced a new caged queen into a nucleus formed on top of the hive, that is above a double screen or division board, the nucleus being made up of bees, brood and stores taken from the powerful parent hive below. Once well established, and the main risk of swarming was over, this nucleus was united with the parent hive. No effort was made to find the old colony queen: in most instances the new queen successfully superseded the old colony queen obviating the need to search for and remove this queen.

Two queen schemes for automatic requeening, swarm control and crop increase

Here is a summary of the requeening schemes employing two queens designed to control swarming presented in the May 1952 and April 1954 issues of the American Bee Journalii broadened to include elements of advanced two-queen hive management set out in the journal in March 1953 where a second queen is commandeered to work in the same hiveiii.

Professor Mykola H. Haydak from Minnesota: The causes of swarming

Mykola Haydak [1898-1971] sets out his approach to control of swarming with a self-evident observationiv:

Swarming is a natural phenomenon in the life of bees. One reads a statement to the effect that if it were not for swarming, there would be no honeybees in the world today.

Haydak follows with a nuanced explanation of the events that precipitate swarm preparation. He notes that, during the development of the hive in spring and where the colony is crowded (27-35 bees per 100 cells), there is an increasing tendency of bees greater than 1-3 days old to be displaced from the brood nest:

In a strong colony, sooner or later, there will be a disproportion between the number of the displaced nurse bees and the space available for egg deposition…

As soon as the queen is around the swarm cells the bees do not bother her. She approaches the swarm cups and deposits eggs in them. As soon as the queen larvae appear the displaced nurse bees can lavishly supply them with food. At the same time the bees stop feeding the queen. The latter feeds herself on honey, deposits less eggs and the size of her abdomen diminishes.

He then went on to describe the loss on the control of the queen over her progeny, the consequent swarm preparations and the subsequent absconding of unemployed bees. The solution to swarming, Haydak observes, is to resolve the supply and demand condition getting out of kilter, that is to keep all the bees well employed. Other authors in these series provide the actual solutions, most employing a second queen to paper over the traditional disruptive approach to requeening that employs the emergency queen replacement impulse.

Mykola’s notes on bee idleness being a key driver of swarming are enhanced by Scottish master beekeeper Bernhard Möbus’s incisive observations on the impact of replete idle bees on their readiness to depart the parent hivev.

Henry A. Schaefer: Swarm prevention

Henry Schaefer, a once president of the US National Beekeepers Federationvi, presents an unconventional approach to swarm controlvii. It is one that I had never heard of or read about except in the writings of Eugene Killionviii and in Henry Schaefer’s reference to Gravenhorst, the latter gentleman also famous for inventing a skep with moveable framesix:

A young queen mated before the nectar flow from the hive she later heads, plus ventilation and plenty of super room [won’t swarm].

In reading Charles Miller’s famous book Fifty years amongst the beesx Schaefer records somewhat amusingly:

It was not long before I was very interested in what Dr Miller had to write about swarm prevention. Here it is: ‘A colony disposed to swarm might be prevented from doing so by blowing it up with dynamite’. But, he says, ‘that would be unprofitable’. He was seeking profitable swarm prevention.

How did Schaefer link his swarm control efforts to requeening. First he reflected on his hive records of the excellent honey crop season of 1927. In that year, amongst his 200 colonies that produced an average of 91 kg (200 lb), there were two standout colonies each producing 194 kg (405 lb) of honey. He had used the standard Demaree swarm control protocol throughout the buildup phase but still pondered on what would constitute a more ideal routine, namely mating young queens from each hive before the honeyflow while also keeping the old queen laying.

He first toyed with using nucleus colonies, each furnished with a queen cell, established above a screen on top of each hive to establish new queens. Though successful in his goal he found this technique was too time consuming. Instead he switched to a scheme, very much the reverse of standard practice, where queens were raised below a screen underneath parent hives.

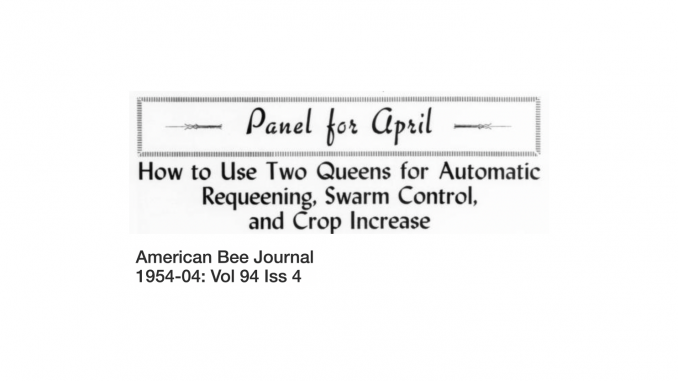

Here is what he did. Each strong colony (Figure 1a) was moved from its parent overwintered position and replaced with a new hive body to which was added a frame of eggs placed between a comb of honey and of pollen after first shaking bees back into the offset parent colony. He then added a couple of shallow supers or a single full depth hive body needed to accommodate returning field bees. To these he added a double sheet of newspaper and a screen with a rear entrance placing the parent hive on top (Figure 1b). As in other schemes, no queens needed to be found – Schaefer assiduously avoided finding them – and the parent colony, if it contained swarm cells, would normally be so depleted of bees that it would automatically destroy any present.

Ten-to-twelve days later all hives were inspected and two good queen cells found in the lower brood box were left in place (Figure 1c) where the best queen would mate and become established. As further contingency, if the upper unit with the old queen above the separator screen had been injured and queen cells had been built to replace her, it was reduced to a two frame nuc and left with one queen cell to avoid a high risk of swarming.

Then, by the commencement of the flow, the screen was replaced with a sheet of newspaper (the newspaper would only have been needed if a nuc board rather than a double screen were employed) to unite the two colonies (Figure 1e). The brood was consolidated at the next apiary visit to facilitate normal honey flow operation (Figure 1f) of hives.

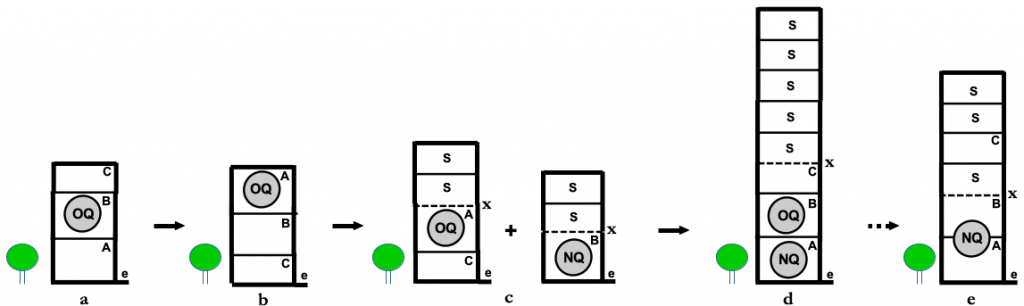

Figure 1 Schaefer requeening plan using two queens: e = entrance; x = excluder; ds = double screen; OQ = old queen; NQ = new queen:

(a) strong over wintered colony;

(b) colony is Demareed;

(c) new queen cells are raised;

(d) a new queen is mated and has her own emerging brood;

(e) the excluder is removed to allow established new queen to supersede the old; and

(f) the brood is consolidated to prepare the colony for the flow.

Carl E. Killion and Eugene Killion: Swarm control and queen rearing in comb honey

The Killions, Carl [1875-1962] and Eugene [1923-2022], lived very long and, one might say, very fruitful lives. These famous father and son producers of comb honey describe a procedurexi that almost fully controls swarming in populous colonies where crowding, essential to the successful drawing out of comb and filling of small honeycomb sections, was needed. As inspiration for their endeavour they refer to Geo Demuth’s Farmers’ Bulletin maximxii:

To bring about the best results in comb-honey, the entire working force of each colony must be heft undivided and the means employed in doing so must be such that the storing instinct remains dominant throughout any given honey-flow.

They surmise that the provision of a young queen early in the season is not sufficient to prevent swarming under their crowded brood nest conditions instead observing:

We did find that any colony requeened with a ripe cell, in the swarming period, after being queenless for eight days, did not swarm nor swarm with a young queen reared and given instead of the cell, after the honey flow was underway.

In an apparent act of self deprecation they stated:

We hesitate when we say that we welcome the swarming season, for fear that any who hear us may think we are just bragging. But we are not: to us, swarming is just as necessary as the nectar and pollen that go into the bees.

While most beekeepers do not operate bees the way the Killions did – few produce section comb honey for sale these days – their technique of breaking the brood cycle and introducing a new queen allowed them to collapse already strong hives to single brood chambers. They could then super the bees with section combs where the bees would focus on comb building and honey production, not swarming or brood raising.

It has always been abundantly clear to me that the Killion technique, outlined in detail in Honey in the Combxiii, would greatly facilitate the operation of the honey-tapping flow hivexiv. If you delve into Eugene Killion’s famous book you will discover that they offset the old queen – in their case not so old girl – in a separate colony to build sufficient stores to provision the parent colony at the end of the season. After all you want the bees to fill sections – or flow combs – not to be diverted into the task of also provisioning the parent hive bees for a far distant overwintering.

However the Killions add a rider to the many who claim to have the solution to swarm prevention:

There are many methods of swarm control. We have tried almost everything recommended in the last thirty years. Most of these sound so very convincing on paper, but if some were left on paper and never tried out in the bee yard, the bees and beekeeper both would benefit.

Newman I. Lyle: Swarm control with the nucleus system

Newman Lyle first reiterates the conventional swarm control measuresxv every experienced beekeeper is familiar with, large brood nests with ample worker and minimal drone comb and a young prolific queen. He then goes on to describe – much in the John Holzberlein style – the technique of introducing a young queen to a nucleus hive established on top of the hive by raising some sealed brood, stores and bees above a double screen. If nothing else the removal of brood from the strong colony puts back the potential of the bees to swarm but there is more to it than that. He had established a new nucleus colony and with a new queen.

Without getting into the detail of his then using this new queen to establish a two-queen hive – a topic for the rather more experienced beekeeper – it is worth noting that this newly established nucleus colony can be used to simply requeen the parent colony. By simply shuffling the brood boxes, after taking the old queen out, he replaced the old queen with a new one in the process greatly reducing the incidence of swarming. Newman provides a number of other subtle hints, not least the potential to use the nuc to requeen other hives in greater need of requeening and – under good conditions – to draw more comb foundation to keep young bees active and less inclined to contribute to the swarming impulse.

John W. Holzberlein from Colorado: Swarm prevention – not swarm control

While the offset nuc method (or the equivalent hive split technique) is perhaps the most assured method for introducing new queens, Winston Dunham [1903-1980]xvi and John Holzberlein [1902-1966]xvii had many other ideas about the usefulness of the technique. They pioneered truly sophisticated plans, ones that integrated swarm control, requeening and colony build up for the honey flow. While both were great exponents of two-queen hive operation, they were equally cognisant of the many simple practices that simply used two queens to effect automatic requeening.

Instead of introducing queens to stand alone nuclei, they adopted the now familiar practice of moving brood and stores from strong hives to a new super located on top of a hive above a double screen (or split board). To this nucleus colony they introduced a new queen rather than a queen cell to accelerate its development. While in most respects the queening is identical to that of the queen introduction technique used by Clayton Farrar, Charles Gilbert and many others, John Holzberlein was focussed on seamlessly requeening whole apiaries. To paraphrase his technique:

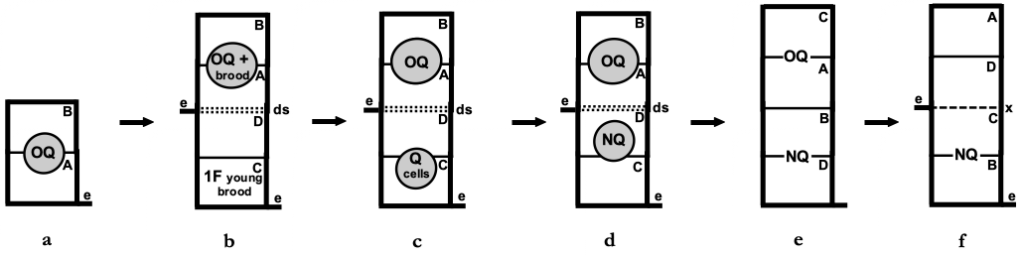

Set a strong colony (Figure 1a) back and in its place put a new bottom board and an empty brood chamber. Quickly sort the frames filling out this empty chamber with unsealed brood and some frames of honey. On top of this place an excluder and above that a further empty super returning the remaining brood combs and stores to this chamber (Figure 1b) after first shaking bees off these frames at the hive entrance. The queen will be in the bottom brood chamber and nurse bees will move up through the excluder to tend maturing and emerging brood. A day or two later the excluder is replaced with a double screen, an empty super is inserted and a new queen is introduced to the older brood and stores in the top super (Figure 2c).

Once the new queen is laying well and has her own brood some weeks later (Figure 1d), the two units are reorganised and united (Figure 2e). Newspaper will be needed only if a solid nucleus board is used instead of a double screen. The old queen is not found, the new queen superseding her.

As Holzberlein notes the early set up process can be concertinaed if the queen is seen when sorting brood (Figure 2a –> Figure 2c) where the queen can be run in at the lower entrance as the excluder is not needed to isolate the queen.

Figure 2 Holzberlein’s requeening system employing two queens: e = entrance; x = excluder; ds = double screen; OQ = old queen; NQ = new queen:

(a) overwintered colony is reversed regularly AB–>BA–>>AB;

(b) frames are sorted and queen is isolated below an excluder (a–>b)

noting that, if the queen is seen, this step can be omitted (a–>c);

(c) the excluder is replaced by a double screen (or nuc board), a super is added and the queen receptive super with old brood is moved up;

(d) a caged queen is introduced and allowed to become well established;

(e) the colony is reorganised so that the new queen supersedes the overwintered queen; and

(f) the colony with a single queen is operated on the honey flow.

The merits of the requeening scheme include:

- never having to locate the old queen;

- forcing both colonies to rebuild their brood nests reducing the risk of swarming;

- minimising the risk of queenlessness;

- avoiding any break in the brood cycle;

- allowing the new queen to be evaluated prior to removal of the old queen; and

- facilitating seamless requeening where the old queen need not be found.

While contrived supersedure (allowing an introduced queen to replace an old queen) is never foolproof, Dunham and Holzberlein were forever watchful of queen performance and always replaced unproductive queens using spare queens they kept in nucs or raised in hive splits. It seems likely that their system of requeening mirrors Don Peer’s remarkable successxviii in effecting supersedure of 80% of 4000 colony queens – introducing a queen cell to the top of hives to replace clapped out queens – late in the season.

If an old queen from the parent colony has had a good performance record and is still laying well, she can be later offset with a few frames of brood and stores as a spare nucleus colony. Such colonies are easily requeened, repurposed as spares or employed to requeen any ailing colonies.

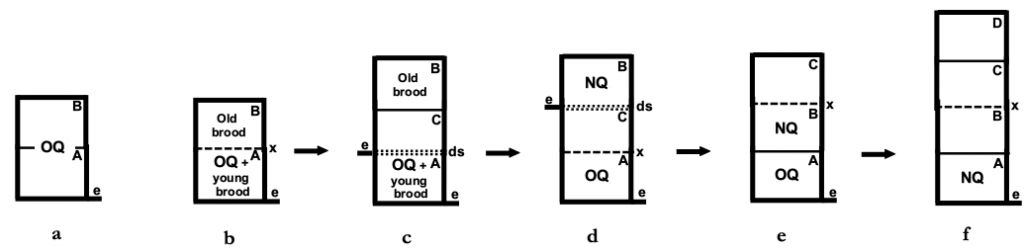

If you only operate a handful of colonies and do not wish to risk of loss of newly purchased queens, you can of course first search for and remove the old queen rather than rely on supersedure to do the requeening for you. If finding that queen in a populous hive proves difficult there is a simple remedy. Offset the brood box on the bottom board with the old queen, move the unit with new queen to the bottom of the stack and search for the old queen once most of the field bees have returned to the parent stand (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Offset hive technique to facilitate finding an old queen: e = entrance; ds = double screen; x = excluder; OQ = old queen; NQ = new queen:

(a) a new queen is well established;

(b) the old queen is offset to facilitate her easy location and removal where the chamber with the new queen is moved to the bottom of stack; and

(c) the brood is consolidated by reorganising boxes.

Elsewhere Holzberlein provides some very candid assessments of the swarming phenomenon. In framing an approach to swarm preventionxix he noted that:

The phenomenon of the swarm is one which I doubt if anyone fully understands in all its phases. We know its basic cause. It is Nature’s means for perpetuating the honey bee colony.

To give substance to this observation he describes the many confounding conditions in relating his long experience of keeping bees, on the one hand feeling that he might line up with the ‘experts’ but on the other hand flummoxed by handling bees in a super swarming year:

But then a swarming year comes along and I know for sure that I belong right where I have rated myself all those years – alone with the learners.

In describing the natural propensity of bees to swarm in beekeeping operations, Holzberlein notes dispassionately that:

Swarming is a natural instinct in bees but it has no place in modern honey production. Our great trouble [in hive] foundation is in trying to curb the urge once it takes possession of a colony. It almost parallels the sheep killing urge that develops in some dogs. The only way to stop it is to destroy the dog. Once a colony makes a firm determination to swarm, gets to the point of having sealed queen cells, with the old queen shrunken up ready for her first venture since her honeymoon days into the wide, blue yonder, there is nothing much we can do about it except to destroy the colony as such.

John Holzberlein identified two effective cures for swarming:

…One is to swarm them, that is, some phase of dividing the old bees and queen from the young bees and brood. The other is to make the colony queenless and queen cell-less, causing it to raise a young queen from scratch.

Neither he concedes is feasible in commercial operation as both are counterproductive to the building bees for the honey flow. His solution is found in a lesson that he learnt from the Nebraskan beekeeper Ralph Barnes, of Oaklands. Barnes mantra was ‘Divide or requeen’.

Holzberlein’s solution was to do both though, for the beginner, it may seem rather confronting:

The kind of dividing I am going to tell you about has no part in making increase. The divide is made all under one cover. The ‘split’ or ‘divide’ is set up over a solid or screened inner cover with an entrance of its own, and given a young queen. It is the beginning of the two-queen system, but right now it is a divide and the best little swarm preventer that you ever tried. Aside from being almost sure-fire swarm prevention it has the added advantage of getting and holding more bees in the field force of the colony than one queen could possibly produce. It keeps them all coming to the same hive, yet divides them at a time when the desire to swarm is almost sure to take over if nothing is done…

It is clear that Holzberlein understood that while two-queen colonies might produce rivers of honey in a protracted honey flow, the essence of productive bee management was to build powerful colonies and to avert the eventuality of bees swarming. He recognised that even the temporary presence of a second laying queen would achieve multiple objectives: less likelihood of colonies to swarm, much stronger bees and seamless requeening.

Charles S. Engle: Automatic Demareeing

Demareeing is an old old chestnutxx and is little more than asymmetric splitting of a colony and doing it under the one roof: most of the brood is relocated well away from the queen. She is left with minimal brood and some stores. In Charles Engle’s approachxxi the queen and a single frame of brood are confined to a bottom brood chamber over which is placed an excluder while the remaining brood is lifted above a new empty super of combs and placed on top of the hive, the technique adopted by Henry Schaefer.

Engle’s very early account of operating bees in the 1920s provides a nuanced application of this seemingly well-practised routine. Like all Demaree plans it upsets the division of labour in the hive and that stops the bees swarming: he could Demaree 100 colonies in one day.

Amongst his many observations he found that supersedure cells raised in the top brood chamber rarely led to swarming or to the establishment of a second queen. This only occurred when virgins could find an escape hole, that is find free flight. Such new queens would turn a super of honey into a super of brood.

He experimented further by routinely provided a flight entrance to the top super employing any new queens he found to promptly requeen the colony after first removing the old queen. Given that he was operating apiaries of 100 or so hives he found locating and removing old queens too time consuming. So he resorted to shaking bees from the top nuc with the new queen in front of the hive entrance discovering that practically every new queen was accepted and had disposed of the old queen, in essence forced supersedure.

Engle had discovered a simple and efficient method of raising queens and requeening. Here it is worth highlighting a technique independently pioneered by David Leehumis and Victor Croker at Australian Honeybee in the southern highlands of New South Wales. They introduce a select queen cell to a nucleus made up of a few frames of young as well as sealed brood and stores established above a queen excluder but without bees: this obviates the need to find the colony queen: the young brood draw bees up through the excluder.

Since cells and virgin queens have no distinguishing pheromone, they found that a queen excluder sufficedxxii to allow establishment of a new queen. By mating queens on strong colonies in isolated yards under flow conditions, most of their hives are successfully established as two-queen hives, the nucleus on top not only benefitting from rising warmth of the colony below but also from free access to colony resources below.

Australian Honeybee are migratory beekeepers so they do not then run their hives as two-queen units for honey flows. Instead they simply move the top super with the new queen to the bottom of the stack and move the bottom super with the old queen onto their truck. Most field bees drift to their parent stands and the truck with a load of single boxes with old queens is driven off into the sunset. Single brood boxes with such queens are depleted of field bees so are easily found. These colonies are re-celled in due course to provide a large number of strong nuclei with new queens.

G.H. (Bud) Cale: Emergency swarm control

Bud Cale, a then editor of the American Bee Journal and a prime instigator of the 1952 Swarming round-up series, provides an overview of the other author contributionsxxiii noting that all swarm control boils down to adopting emergency measures. Yet he concedes that the contributions of the likes provided by John Holzberlein suggest that swarming should be anticipated. Proactive measures such as splitting all strong colonies will change the mood of bees and keep them in that active expansionist condition essential to building colonies needed to gather large amounts of honey.

Like any beekeeper with a good grasp of the swarming impulse, Cale noted that:

The age of the queen has much to do with the amount of swarming because supersedure will be carried out at the same time swarming is usually imminent. The older queens therefore will be more involved in swarming than the young ones.

The key swarm control strategy that Cale floats, one he highlights in The Hive and the Honey Beexxiv, is to switch the location of strong and weak colonies. He notes this will only work if any started queen cells are first removed. It is a strategy that would be unwise to adopt unless you first checked your bees for brood diseases but it is a simple practice to adopt when you have a paddock full of beehives in need of emergency swarm control. Such hive shuffling is certainly unsuitable where parasitic mite infestation is not well controlled or where American Foul Brood is masked by use of antibiotics, a practice illegal in Australia.

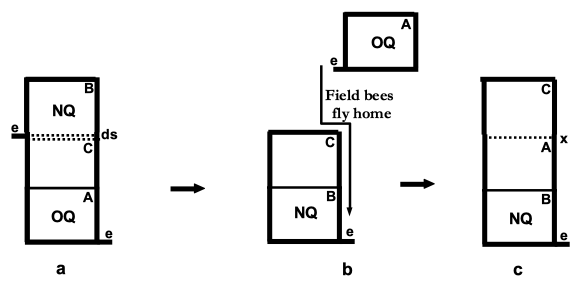

In a later foray Cale outlines a variation of the traditional hive splitting method of swarm control (Figure 4)xxv. A hive with double brood nest hive with an additional shallow food chamber (Figure 4a, super C) is first established. By spring the upper supers (B and C) are occupied by brood when the supers are reversed (Figure 4b). In most instances the queen soon migrates to the now upper super A.

About two weeks later the colony is split and supered when a caged queen securely corked is immediately introduced to the most likely queenless split (Figure 4c, super B), most bees drifting to the parent stand (Figure 4c, super A). Five days later, if hive B has no eggs, the cork is removed and the candy punctured to facilitate quick release of the queen. If, alternatively, the old queen is found laying in hive B, the caged queen is simply returned to the parent stand hive A where – after removal of the cork – she will be quickly released.

Cale’s plan was simple and flexible: he did not need to locate the parent hive queen when making the split and introducing the caged and securely stoppered queen. So he got the bees to tell him which of the splits had the laying queen but this required him to check for and remove any started queen cells if one of the splits were queenless.

Once the new queen was well established the colonies were united and supered, Cale noting that in most cases both queens both continued to lay for some time.

Figure 4 Bud Cale’s smart split to arrest swarming: e = entrance; x = excluder; s = super; OQ = old queen; NQ = new queen:

(a) strong overwintered colony;

(b) the brood boxes are reversed and left for several weeks;

(c) the colony is split and queen introduced to unit without eggs after five days (most likely brood box B);

(d) the colony is reunited and supered after new queen is well established; and

(e) the new queen supersedes the overwintered queen and supers are extracted and returned to the bottom of the honey super stack or removed as the flow ebbs.

The scheme is notable for its extraordinary simplicity and any requirement to find queens.

Loren F. Miller from Minnesota: Two queens to reclaim weak colonies

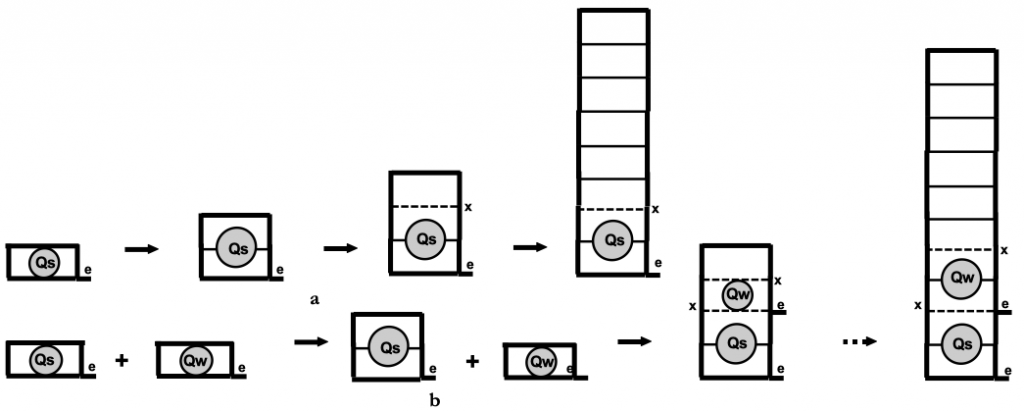

In northerly Minnesota Loren Miller started his bees each spring from package bees in shallow brood bodies, feeding them heavily to establish them quicklyxxvi. He started colonies as single-queen hives in shallow hive bodies with a full frame of honey, a week later adding a shallow super where needed (Figure 5a). To recover weak colonies, and knowing that all colonies had young queens, Miller supered them above strong colonies – those that came away promptly – recognising that the two queens laying together (Figure 5b) would produce more honey than had the hard case colonies been left alone to flounder.

In a more fulsome earlier articlexxvii Miller concedes that operating two-queen colonies can be problematic:

I found that all hives run as two-queen colonies are difficult to operate without costly extra visits and some disappointing results. Some swarm, some lose all their workers to one queen, some develop so much late brood they finally make a wonderful crop of late off-grade weed honey.

Like others Miller succeeded in building his bees faster with a second queen though only under conditions where it proved profitable to do so.

Figure 5 Miller package bee weak colony rescue plan: e = entrance; x = excluder; Qs = strong queen colony; Qw = weak queen colony:

(a) course for normal single-queen colony expansion: and

(b) employing weak colonies that come away slowly to further strengthen strong colonies.

Eugene S. Miller from Indiana: Swarm control with extracted honey

In reflecting on Loren Miller’s and the very famous Charles Miller’s [1831-1920] contributions to concomitant requeening and swarm control, it was hard to ignore the contributions of their namesake, once President of the American Honey Producers’ League and early pioneer of commercial beekeeping in North America, Eugene Miller [1861-1958]. He had an uncanny grasp of effective hive management at an apiary scale (Figure 6).

Figure 6 One of Eugene Miller’s bee yards 1918xxviii

Eugene Miller provides us with what would now appear to be a fairly conventional approach to swarm controlxxix for his era starting with a remarkable claim:

In the production of extracted honey, swarming can be prevented. It has been proved by more than six years without a swarm in a yard averaging about 50 colonies. In fact, the bees seldom started any queen cells. I believe this record can be duplicated by anyone who has a good strain of Italians and who will use the method which I will attempt to outline.

He went on to describe how he did this:

Confine the queen to the lower story. If you have trouble finding her just shake off bees and queen and let them run in under the queen excluder. Next, use as a second story a deep super of drawn combs, which is to be left in place during the next twelve months as a food chamber. Then place on top of this what was previously the second story. Time required, about 15 minutes per colony.

Miller’s scheme avoids the classic labour intensive approach of regularly reversing brood boxes to delay the onset of swarming. Instead he used an excluder to confine the queen to a single largely empty lower brood box where the queen was forced to rebuild her broodnest, a de facto Demaree. He later conducts a more formal Demaree claiming that the overall scheme had entirely prevented swarming in his apiaries:

Then about June 1 [our 1st of December or quite a lot earlier given local ACT region conditions] or whenever the brood chamber becomes crowded replace the brood with drawn combs, moving to the top or fourth story all brood except one comb, which is left below so that the bees will not desert the queen.

He emphasises that this second operation must be conducted before the bees have any inclination to swarm and certainly well in advance of swarm queen cell construction. He points out that this measure removes the brood nest congestion inimical to colony expansion and Haydak’s notion of supply and demand condition getting out of kilter.

Eugene Miller does not signal how he went about requeening his colonies but he did unite weak colonies and did set up his colonies with new queens – he lived in the US mid northwest – in August, that is mid to late summer. This would have ensured that his colonies came away early in spring and be headed by young queens, a strategy that would have averted the need for spring requeening of his colonies.

Elsewhere Eugene Miller signalled a few other essentials, notably the use of young queens, but he claimed his system was essentially foolproof and that it was backed by years of experience. In a May 1943 articlexxx he lists all the measures one should take to prevent or minimise swarming:

- queens should be bred only from the best non-swarming stock…;

- failing queens, and all queens over two years old, should be replaced, otherwise attempts at supersedure may tend to induce swarming;

- defective combs… should be discarded…;

- suitable ventilation should be provided with an entrance to the hive at least 7/8 inch deep by the full width of the hive;

- sufficient room [should be provided] for the expansion of brood and for storage of honey…; and

- …the excess of young bees and the emerging brood from the combs to be occupied by the queen [should be removed].

Much earlier he had briefly noted a scheme for successfully starting a queen in the top super using a select stock queen cell in lieu of those raised by the colonyxxxi. This technique is now part and parcel of new queen establishment amongst time-starved commercial apiarists.

It seems likely that all these schemes are imbedded into commercial practice but are not well known amongst sideline beekeepers. To the extent that these schemes are a much simpler alternative to the operation of doubled and two-queen hives and that they achieve seamless requeening, they could make backyard beekeeping a more productive pursuit especially if this resulted in annual or biennial requeening.

Readings

iThe plans by Winston Dunham, Clayton Farrar and others to operate two-queen hives (hives with more than one queen in the same hive) are not covered as their prime goal was to supercharge honey production not just swarm control and requeening.

iiHaydak, M.H., Schaefer, H.A., Miller, E.S., Killion, C.E. and Killion, E., Lyle, N.I., Holzberlein, J.W., Engle, C.S. and Cale, G.H. (1952). Swarming round-up. American Bee Journal 92(5):181, 189-198. https://archive.org/details/sim_american-bee-journal_1952-05_92_5/mode/2up

Farrar, C.L., Miller, L.F., Dunham, W.E., Schaefer, E.A., Holzberlein, J. Jr, and Cale, G.H. (1954). Panel for April: How to use two queens for automatic requeening, swarm control, and crop increase. American Bee Journal 94(4):128-132. https://archive.org/details/sim_american-bee-journal_1954-04_94_4/page/128/mode/2up

https://archive.org/details/sim_american-bee-journal_1954-04_94_4

iiiFarrar, C.L., Dunham, W.E., Miller, L.F. and Holzberlein, J.W. (1953). Spotlight: Two-queen management. American Bee Journal 93(3):107-115; 117. https://archive.org/ details/sim_american-bee-journal_1953-03_93_3/page/107/mode/1up

ivHaydak, M.M. (1952). The causes of swarming. American Bee Journal 92(5):189-190. https://archive.org/details/sim_american-bee-journal_1952-05_92_5/mode/2up

vMöbus, B. (April 1987). The swarm dance and other swarm phenomena Part I. American Bee Journal 127(4):251, 253-255.

Möbus, B. (May 1987). The swarm dance and other swarm phenomena Part II. American Bee Journal 127(5):356-362.

viRahmlow, H.J. (ed.) (September 1952/August 1953). Schaefer new beekeepers federation president. Wisconsin Horticulture 43:119. https://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/WI/WI-idx?type=turn&id=WI.WIHortv43&entity=WI.WIHortv43.p0119&isize=text

viiSchaefer, H.A. (1952). Swarm prevention. American Bee Journal 92(5):190-191. https://archive.org/details/sim_american-bee-journal_1952-05_92_5/mode/2up

Schaefer, H.A. (1954). The Shaefer two-queen swarm control method. American Bee Journal 94(4):131. https://ia804500.us.archive.org/23/items/sim_american-bee-journal_1954-04_94_4/sim_american-bee-journal_1954-04_94_4.pdf

viiiKillion, E.E. (1981). Honey in the Comb. Dadant & Sons. Inc, Carthage, Illinois.

ixMorrison, W.K. (1907). Gravenhorst’s system in Germany: The peculiar form of his hive and frame. Gleanings in Bee Culture 35(1):30-31. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.31951d00953180r;view=1up;seq=24

xMiller, C.C. (1911). Fifty years among the bees. A.I. Root Company, Medina, Ohio, Rearing queens in hive with laying queen, pp.310-312. https://archive.org/details/ fiftyyearsamongb00mill

xiKillion, C.E. and Killion, E.(1952). Swarm control and queen rearing in comb honey. American Bee Journal 92(5):190-191. https://archive.org/details/sim_american-bee-journal_1952-05_92_5/mode/2up

xiiDemuth, G.S. (1919). Commercial comb honey production. US Department of Agriculture Farmers’ Bulletin 1039, 41pp. https://ia804509.us.archive.org/26/items/CAT87202962/farmbul1039.pdf

Demuth, G.S. (1917). Comb honey. US Department of Agriculture Farmers’ Bulletin 503. Washington Government Printing Office. https://ia802209.us.archive.org/21/items/CAT87201971/farmbul0503.pdf

xiiiKillion, E.E. (1981) pp.79-80, 96 loc.cit.

xivHow flow works (downloaded 2 June 2022). https://www.honeyflow.com.au/pages/how-flow-works#:~:text=Plastic%20foundation%20in%20beehives%20is,tube%20and%20into%20your%20jar

xvLyle, N.I. (1952). American Bee Journal 92(5):194-195. https://archive.org/details/sim_american-bee-journal_1952-05_92_5/mode/2up

xviDunham, W.E. (1943). The modified two-queen system. American Bee Journal 83(5):192- 194, 203. https://archive.org/details/sim_american-bee-journal_1943-05_83_5/page/192/mode/2up

Dunham, W.E. (1947). Modified two-queen system for honey production. Bulletin of the Agricultural Extension Service, the Ohio State University 281:1-16. Cited by Butz, V.M. and Dietz, A. (1994). The mechanism of queen elimination in two-queen honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) colonies. Journal of Apicultural Research 33(2):87-94. https://scholar.google.com.au/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Dunham%2C+W.E.+%281948%29.++Modified+two-queen+system+for+honey+production.&btnG= doi.org/10.1080/00218839.1994.11100855

Dunham, W.E. (May 1948). Modified two-queen system for honey production. [Part of Bulletin No. 281, issued March 1947 by Agricultural Extension Service, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio.] and published as

Dunham, W.E. (1948). Modified two-queen system for honey production. Gleanings in Bee Culture 76(5):277-281. https://archive.org/details/sim_gleanings-in-bee-culture_1948-05_76_5/page/276/mode/2up

Dunham, W.E. (1951). The Ohio modified two-queen system. Gleanings in Bee Culture 79(4):212-214. https://archive.org/details/sim_gleanings-in-bee-culture_1951-04_79_4/page/212/mode/2up

Dunham, W.E. (1953). The modified two-queen system for honey production. American Bee Journal 93(3):111-112. https://archive.org/details/sim_american-bee-journal_1953-03_93_3/page/110/mode/2up

Dunham, W.E. (1954). Dunham’s modified two-queen plan. American Bee Journal 94(4):130-.131. https://archive.org/details/sim_american-bee-journal_1954-04_94_4/page/130/mode/2up

xviiHolzberlein Jr, J. (1954). Another way to start two-queen colonies. American Bee Journal 94(4):131-132. https://archive.org/details/sim_american-bee-journal_1954-04_94_4/page/131/mode/1up

xviiiJay, S.C. (1981). Requeening queenright honeybee colonies with queen cells or virgin queens. Journal of Apicultural Research 20(2):79-83. doi.org/10.1080/00218839.1981.11100476

xixHolzberlein Jr, J.W. (1952). Swarm prevention–not swarm control. American Bee Journal 92(5):195-196. https://archive.org/details/sim_american-bee-journal_1952-05_92_5/mode/2up

xxDemaree, G. (1892). How to prevent swarming. American Bee Journal 29(17):545-546.

https://archive.org/details/sim_american-bee-journal_1892-04-21_29_17/page/544/mode/2up

xxiEngle, C.S. (1952). Automatic Demareeing. American Bee Journal 92(5):197. https://archive.org/details/sim_american-bee-journal_1952-05_92_5/mode/2up

xxiiSuccessful introduction of a caged queen to a nucleus colony requires separation of the nucleus from the parent colony, i.e. use of a blanketing inner cover, a nucleus board or a double screen.

xxiiiCale, G.H. (1952). Emergency swarm control. American Bee Journal 92(5):198. https://archive.org/details/sim_american-bee-journal_1952-05_92_5/page/198/mode/2up

xxivCale Sr, G.H., Banker, R. and Powers, J. (1979). Management for honey production, Chapter XII, pp.382-383 in The Hive and the Honey Bee. Extensively revised edition, fifth printing.Dadant & Sons, Hamilton, Illinois.

Cale, G.H. (1943). Relocation as a means of swarm control. American Bee Journal 83(5):190-191. https://archive.org/details/sim_american-bee-journal_1943-05_83_5/page/190/mode/2up

xxvCale, G.H. (1954). Reversal, separation and reunion. American Bee Journal 94(4):128-132. https://archive.org/details/sim_american-bee-journal_1954-04_94_4/page/132/mode/2up

xxviMiller, L.F. (1954). Two queens to reclaim the weak colonies. American Bee Journal 94(4):130. https://archive.org/details/sim_american-bee-journal_1954-04_94_4/page/130/mode/2up

Victors, S. (2001). Two queen hive system from package bees. Alaska Wildflower Honey, 8pp. http://sababeekeepers.com/files/Two_Queen_Hive_System_From_Package_Bees.pdf

Winston, M. and Mitchell, M. (1986). Timing of package honey bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) production and use of two-queen management in southwestern British Columbia, Canada. Journal of Economic Entomology 79(4):952-956. https://discovery.csiro.au/primo- explore/fulldisplay?docid=TN_proquest14497293&context=PC&vid=CSIRO&lang=en_ US&search_scope=All&adaptor=primo_central_multiple_fe&tab=default&query=any,contains,Winston,%20M.%20and%20Mitchell,%20M.%20 (1986).%20%20Timing%20of%20package%20honey%20bee&offset=0

xxviiMiller, L.F. (1953). Crop insurance with two queens. American Bee Journal 93(3):113, 117. https://archive.org/details/sim_american-bee-journal_1953-03_93_3/page/113/mode/1up

xxviiiShook, S. (May 13, 2017). Honey industry of Porter County referencing The Country Gentleman (November 23, 1918) 865:29. http://www.porterhistory.org/2017/05/honey-industry-of-porter-county.html

xxixMiller, E.S. (1952). Swarm control with extracted honey. American Bee Journal 92(5):192-193. https://archive.org/details/sim_american-bee-journal_1952-05_92_5/page/192/mode/2up

xxxMiller, E.S. (May 1943). Swarm prevention. American Bee Journal 83(5):194, 203. https://archive.org/details/sim_american-bee-journal_1943-05_83_5/page/194/mode/2up

xxxiMiller, E.S. (1932). Mating queen from a top story. American Bee Journal 72(10):403. https://ia903403.us.archive.org/29/items/sim_american-bee-journal_1932-10_72_10/sim_american-bee-journal_1932-10_72_10.pdf