Alan Wade

The one colony – One queen principle

One of the fundamental operating tenets of any honey bee colony is that it will support only one queen, an innate characteristic of the eleven or so species of honey bee. At least that is the trend, one best found in swarming where both the parent and budded off (swarmed) colony end up with just one queen. That was forced by the selective evolutionary process of ceding all reproductive capacity to one individual, the single queen (or gyne) selected to head the colony.

Yet remarkably there are ‘temporary’ exceptions to the one colony – one queen principle. The most notable is ground in the reality that the immortal bee colony – excepted by demise due to predation, disease or starvation – must periodically replace its ageing queen and indeed must also invest in replenishing its supply of sperm, the latter only possible by starting with a new queen and, at a local population scale, ample drones. The simple process of natural queen succession, so eloquently demonstrated by the great researcher Colin Butler, means there are occasions when the colony has no option but to replace its ailing monarch. The colony, in a parlous state of a failing queen will support both mother and a replacement daughter queen. Both queens may not only coexist but also lay harmoniously together. But even here, and usually after a short time, the old queen will disappear and the colony will end up headed solely by a new and vigorous daughter queen.

The principle of one colony, one queen would indeed appear inviolate.

Rules are made to be broken

It therefore remarkable that the one queen rule might be deliberately broken. One common situation where this occurs is when the colony fails to signal that a second queen (or look alike usurper called a gyne) is present but goes unrecognised.

A good pal, Cormac Farrell, hived a recombinant swarm (coalesced prime swarms each with a laying queen) a couple of seasons back. It happily settled and went on to establish likely separate brood nests, both queens continuing to lay well. That was until the game was up, the queens found each other and the colony reverted to the single queen condition.

The other situation where two queens turn up occurs amongst some African races of Apis mellifera. Here a seeming ‘generic throwback condition’ is displayed by the Cape Honey Bee, Apis mellifera capensis and probably by its sympatric (living nearby) ally, the African Honey Bee, Apis mellifera scutellata. The Cape Honey Bee in particular can support multi gyne colonies that may persist for a year or more, while they are also well known for parasitising African Honey Bee colonies and can form two-queen colonies, one from each race. But that, so to speak, is a race to the bottom, the colony dwindles and dies. Indeed whole African Bee apiaries have been wiped out as a result of this mixing of the races.

That is a complex story and one we need not pursue.

The early commercial Farrar-style two-queen colonies were more piggybacked single queen hives than true two-queen colonies. In these, queens were kept well apart, the bees not recognising their dual queen status, albeit with a very large workforce and with the upper brood nest benefitting from rising warmth generated by the presence of brood below.

The end result of all these experimentation was the development of commercial two-queen operations that greatly increased honey production but were so fearsomely complex to operate that – except in the hands of exceptionally competent beekeepers such as Robert Banker and Floyd E. Moeller – they have been deemed too complex and challenging to operate. The myth of their being too difficult to run and too hard to move persists to the present day. This is a pity given what is now known as we shall see.

Step in the unsung two-queen hive hero John Alexander Hogg

In an almost forgotten series of experiments, John Hogg demonstrated a finding, originally made by E.W. Alexander and buried in the beekeeping literature, that two queens could be maintained in any honey bee colony and in close proximity to one other. Simply distilled, the bees (the workers) can accept a second queen but the queens must be kept apart (a queen excluder suffices) to avoid accidental encounter. He also delineated the importance of worker bees being carefully conditioned to accept two queens.

Hogg says it all:

The main problem in establishing two queens in the [two-queen] hive is

acceptance of the queens by the bees, just as in single queen operation.

He further demonstrated that juxtaposed two-queen units, each with their own separate hive entrance, could be simply achieved. The colony now had a consolidated brood nest (CBN) with two queens separated only by an excluder:

Brood is continuous throughout the two chambers. The brood nest is

indistinguishable from that of a single queen occupying two brood chambers.

The exciting prospect thus existed of running a two-queen colony in just the same way as one would a single queen colony – all honey supers are stacked on top and operated exactly the same way as one would a conventional single-queen bee hive. However the colony is far less swarm prone and is far more productive.

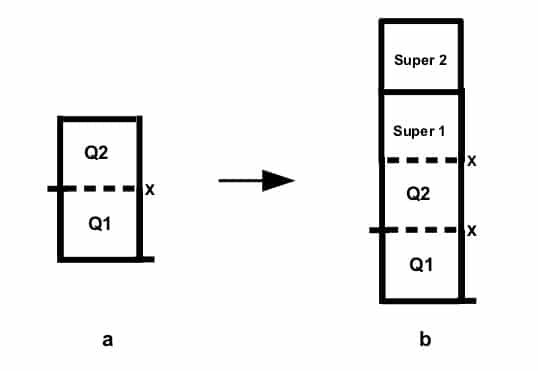

Figure 1 Operating the Consolidated Brood Nest (CBN): x = excluder; (a) consolidated brood nest; (b) supered as for single queen operation for honey flow – second upper excluder is optional

Not being content with having ‘invented’ the CBN two-queen hive, Hogg went on to explore universal conditions underpinning colony acceptance of queens. He drew his conclusions from his understanding of the role of queen bee mandibular and worker bee alarm pheromones. From his experiments he drew the conclusion that the conditions for successful acceptance of two, maybe more, queens to a colony were identical to those required for conventional single queen replacement.

Thus, in practice, you can always introduce one or two queens to a colony recently dequeened, but never a second queen directly to an already queenright hive. Eight colony conditions influence successful queen introduction:

- making a colony gyne (queen) free, ideally one to two days before a new queen or queen cell is introduced. This is an absolute prerequisite. The colony must be cleared of its reigning queen and indeed also of any additional supersedure queen, virgin queens and ripe and developing queen cells. Further it must be free of large numbers of laying workers (gynacoid queens), a condition induced by an extended period of queenlessness. It’s good practice to search all brood frames after one queen is found and removed. Often enough a second supersedure queen is present. Both queens should be removed;

- timing of queen introduction to coincide with a strong nectar flow. This or feeding bees sugar water to simulate a honey flow greatly increases the chance of queen acceptance;

- timing of queen introduction to avoid periods when bees are ill-tempered. Wait till that thunderstorm has passed, and avoid cold wet or any other conditions where you think you are likely to get stung;

- employing disruptive techniques that mask the colony defence alarm system. One technique is to smoke the bees well, necessary anyway if the bees are aggressive and in need of quietening down to effectively search for the old queen:

- using queen release delaying tactics. Slowing down queen release, think mailing cage queen candy, allows the new queen to acquire colony odour and improves her acceptance. Caged queens, kept in the brood nest without escort bees but with covering mesh screen that allow nurse bees to feed her, have been shown to further improve queen acceptance;

- matching conditions to those of the queen being replaced, especially critical to the introduction of two queens, is important. In the two queen introduction scenario, both the queens and the brood status of each chamber need to be closely matched;

- requeening using a nucleus colony. The nucleus queen with attendant nurse bees and frames of brood and stores promotes conditions very similar to those of the parent colony to be requeened. It is the most reliable method of queen introduction to large colonies; and finally

- releasing any queen or gyne (e.g. a ripe queen cell) onto frames into a small colony containing only young nurse bees and emerging bees. This technique involves first gently shaking older working bees from brood frames in making up a nuc. The technique almost invariably succeeds and a queen in any condition can be introduced without protection though a little smoke may help.

The rules applied to requeening of single queen hives

Unless a honey flow is in progress, good rules of thumb are to feed the bees in advance of queen introduction and

- to use either caged mated queens to directly requeen a hive; or better

- to make up and feed nucs to accept queens or queen cells.

Making up nucleus colonies also buys you time. You don’t have to find the old queen immediately providing of course that you take care not to transfer the parent colony queen to the nuc. You can also make up nucs several days in advance of the scheduled arrival of queens and reunite nucs promptly if queens to not arrive on time or die in transit. Further you can allow both queens to lay for a while so there is no interruption in the brood cycle and you do not risk losing both the parent colony queen that you have disposed of and possibly the newly introduced queen. This strategy ensures you always have the backup old queen at hand: you can even go to great lengths and swap out the old queen to the nuc and use her brood to strengthen the parent colony.

Waiting for the new nucleus queen in the nuc to raise her own emerging brood and nurse bees lines up well with rules 6 and 7.

The rules distilled to double queening hives

The rules to achieve successful double queening follow the same general pattern, but even greater care is required to avoid the natural tendency of the hive to return to single queen status. Like most beekeepers I’ve lost queens – especially starting up a two-queen hive, a condition arising from poor reading of colony condition and colony gyne status.

If conditions in the two nests to be queened are not closely matched, worker bees may ball one queen perceiving one of the queens to be an intruder. Secondly if one queen is of inferior status, say the second queen is unmated or not also laying, then the queen will not meet colony expectations and one will be superseded.

In early experiments Hogg got around this situation by piggybacking colonies separating the two single queen nests with a double screen. Weeks later, when both queens were laying well and had their own established brood nests they were of equal status. They could be simply papered together using only an excluder to keep them apart.

But this stepwise approach delays set up and requires more work and more apiary visits than may be needed. Hogg experimented to set up two-queen hives directly and found that the rules had to be strictly enforced for double queening to be successful. For example two caged queens can be introduced at the same time into a strong and just dequeened double brood nest colony employing, of course, a separating queen excluder.

However such short cut methods can be fraught. You really do need to have a clear and understanding of the requeening principles. Direct setup requires that the brood must be matched like-to-like in both brood boxes and that the bees in the upper brood chamber must first be trained to enter the top and usually opposite-facing entrance.

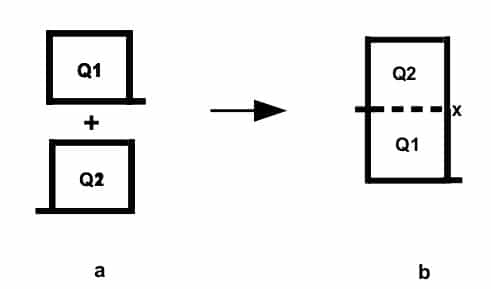

For the record I’ve found that the best and most reliable technique is to simply unite two colonies in the same condition (Figure 2) in much the same way one unites a nuc with a colony to be requeened. Ideally this combining process should be done at the beginning of the main honey flow and before gear gets too heavy or difficult to organise.

Figure 2 Uniting two single-queen colonies to establish consolidated brood nest (CBN): x = excluder: (a) single queen hives with entrances in opposite directions; (b) consolidated brood nest

Subsequently Hogg established three basic techniques for double queening of honey bee colonies. Remarkably Hogg went on to make other important findings, for example, using the CBN two-queen hive to achieve automatic requeening of hives at season’s end.

We will revisit the topic of set up and operation of two-queen colonies in Part II.

Intriguingly any full reading of the operation of two-queen colonies goes way beyond their setup to increase honey production or to enhance the pollination power of honey bee colonies. Temporary two-queen hives can be employed to accelerate development of nucleus colonies, to quickly establish swarms, to split hives to eliminate the risk of swarming in mid spring and tο achieve automatic requeening of hives. The latter strategy – replicating queen supersedure principles – avoids any need to find the old queen, ad is a technique widely employed by commercial beekeepers faced with the prospect of needing to requeen large apiaries.

In his Juniper Hill (two-queen) plan, a late and final project, Hogg modified the famous Killion method for producing section comb honey to spectacular effect. In this plan may lie the real answer to effective operation of flow hives.

Readings

Alexander, EW (1907). A plurality of queens without perforated zinc. Gleanings in Bee Culture 35(23):1136-1138. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.31951d00953180r;view=1up;seq=

Banker, R. (1968). A two queen method used in commercial operations. Apiacta 2, 4 pp. https://www.google.com.au/search?q=Banker%2C+R.+(1968).+A+two-queen+method+used+in+commercial+operations.&oq=Banker%2C+R.+(1968).+A+two-queen+method+used+in+commercial+operations.&aqs=chrome..69i57j69i60j69i59.22414j0j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8

Banker, R. (1979). Part B. Two-queen colony management. The Hive and the Honey Bee (1975 extensive revision) pp. 404-410, Dadant and Sons Inc., Carthage, Illinois.

Butler, C. (1974). The World of the Honeybee. Collins New Naturalist, London; Butler, C. (1962). Transactions of the Royal Entomological Society of London 114(1): 1-29.

Hogg, J.A. (1983a). Methods for double queening the consolidated broodnest hive: fundamentals of queen introduction. Part 1 The Fundamentals of Queen Introduction. American Bee Journal 123:383-388. http://www.twilightmd.com/Samples/Hogg/Hogg_Halfcomb___Publications/ABJ_1983_1May.pdf

Hogg, J.A. (1983b). Methods for double queening the consolidated broodnest hive: the fundamentals of queen introduction. Part 2 Conclusion. American Bee Journal 123:450-454. http://www.twilightmd.com/Samples/Hogg/Hogg_Halfcomb___Publications/ABJ_1983_2June.pdf

Hogg, J.A. (2005). The Juniper Hill plan for comb honey production, improved two-queen system. American Bee Journal 145(2):138-141. http://www.twilightmd.com/Samples/Hogg/Hogg_Halfcomb___Publications/ABJ_2005_February.pdf

Killion, E.E. (1981). Honey in the Comb. Dadant & Sons. Inc, Carthage, Illinois.

Moeller, F. E. (April 1976). Two queen system of honeybee colony management. Production Research Report 161, Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture, 15 pp. Washington DC 20402. http://naldc.nal.usda.gov/download/CAT87210713/PDF and http://mesindus.ee/files/52221134-2-queen-management.pdf

.

Be the first to comment