Alan Wade and Dannielle Harden

Canberra Region Beekeepers

Teaser for Somerset Beekeepers’ Association Webinar

6 January 2022

The gamble of running multi-queen colonies ‘According to Hoyle’

Edmond Hoylei (1672 – 1769) is famous for establishing game of Whist and other card playing etiquette. If we were to run bees ‘According to Hoyle’, we could ever only do so in hives headed by a single queen.

Only one queen rules

Some 30 million years ago:

- ancestral honey bees such as Apis henshawi had the same worker morphologyii as extant honey bees signalling that they likely ran best with a single queen;

- a queen in such a social group would have initially mated with one drone but colonies evolved to better survive when the queen mated with multiple drones;

- honey bees stuck to the single-queen formula; and more recently

- the first beekeepers arriving on the scene (from ~4000 y bp) soon learnt that trying to introduce an extra queen was more or less impossible.

Fossil Apis henshawi ~ 23 my bp

Honey bees have a clear preference for running with a single queen! But could this rule be broken?

Exception proves the rule

Surprising as it may seem honey bee colonies can sport an extra queen, the most notable examples of which include:

- the fleeting multi-gyne (a gyne is a potential as opposed to a laying queen) condition when bees are preparing to swarm;

- the occasional persistence of two or three laying queens when bees are replacing their ailing queen (supersedure);

- the recombinant prime swarm condition where two laying queens may both settle and lay in the one colony; and

- the Cape Honey Bee that parasitises West African Honey Bee colonies and that survives briefly as a two-queen hive.

Should you try to run hives with extra queens?

The benefits of running hives with extra queens are that more bees equates to more honey, more queen pheromone means less swarming and that colonies are unlikely to become queenless.

These advantages must be traded off against the fact that there are some serious downsides.

Firstly any drought period, case of poor queen performance, or any bumper flow condition – one that leads to giant swarms – results in colonies reverting to the single-queen hive condition. Throwing in the fact that giant colonies are physically difficult to manage, and that timing of build up and extraction is doubly challenging, has made us wonder whether all the extra effort in running two-queeners is worthwhile. However beekeepers like us, bored with the routine of just trying to keeping bees in order, have started the whole learning process again and given extra-queen beekeeping a shot.

The single-queen hive

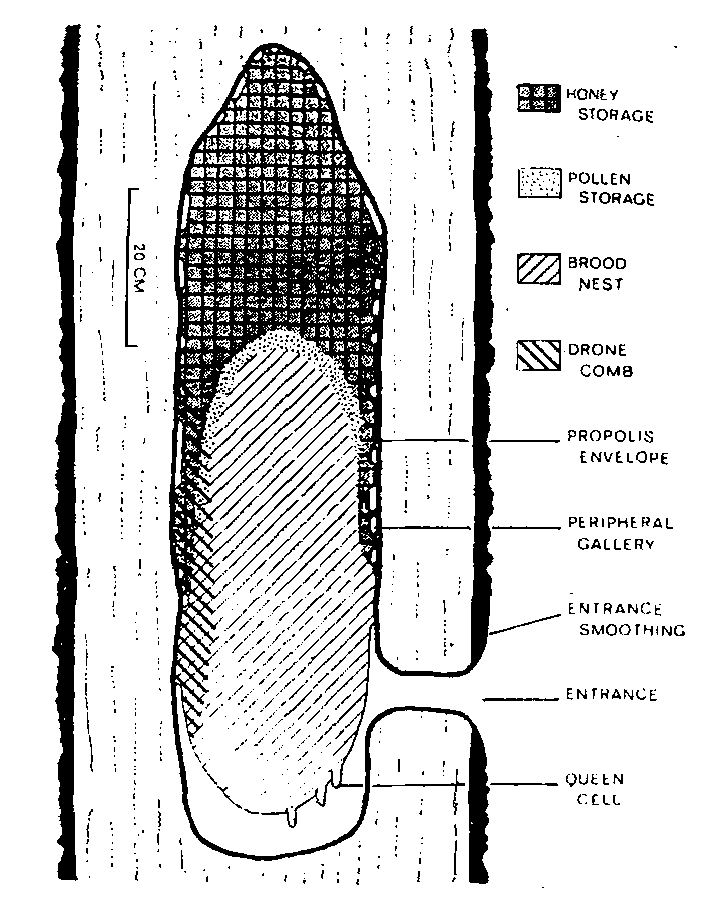

The classic Seeley and Morse 1976 study of wild hivesiii is a good place for us to start. Here we learn about hive architecture and the dynamic nature of the superorganism we call the honey bee colony.

We note first that while the colony persists all its members are regularly replaced. We once thought the honey bee colony were potentially immortal. Tom Seeley soon put us right with another study of wild hives suggesting that they have a mean lifespan of around seven years as queen replacement occasionally fails. Most unmanaged and wild hives swarm annually so that means a new colony queen every twelve or so months. Where such swarming is controlled we’ve observed that most queens are replaced every 12-18 months anyway.

Classic Seeley-Morse findings of chopping down trees with wild hives

So we learn that:

- to maintain colony vigour, honey bees replace their queens regularly;

- honey bees can, in theory, support more than one queen;

- Demareeingiv (artificial swarming) – where the queen is isolated from most of her brood using an excluder – can give rise to a two-queen colony; and

- honey bee colonies with an extra queen have a strong tendency to revert to the single-queen condition.

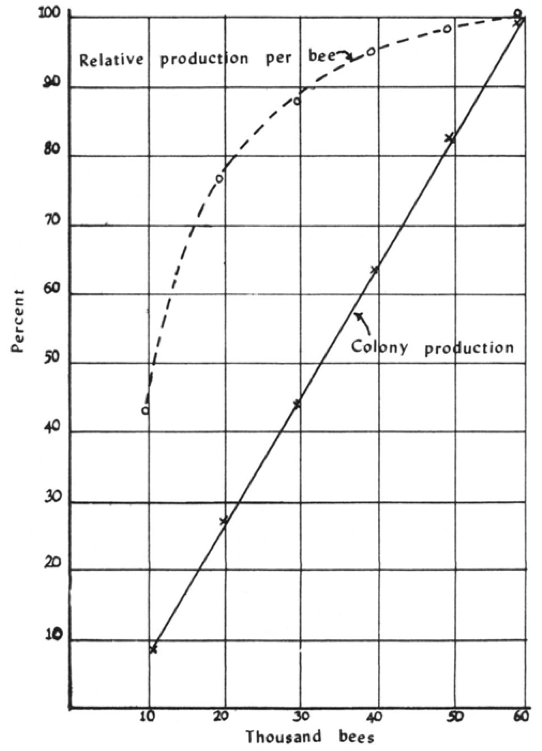

Farrar showed very elegantly that honey yield correlates closely with bee numbersv.

Farrar model of colony production in relation to bee numbers

Since the slope of yield to bee numbers turns out to be rather greater than one, doubling the number of bees more than doubles the yield of surplus honey.

How we came to two-queen beekeeping

The lure of an extra queen producing more bees and thus more honey has long fascinated beekeepers but, in execution, had eluded all but the most capable operators.

First though we relate tales of:

- Dannielle’s narrative of how a small back yard and not enough room to run all the hives she wanted motivated her to run two-queen hives from the outset; and

- Alan’s early foray into running about eight two-queen hives on a giant honey flow back in the early 90s and getting about a tonne of honeyvi. There is tons more information on doubled and two-queen hives in Alan’s book published by Northern Bee Books.

Rivers of honey aside, we have been severely chastened by the natural proclivity of bees to revert to their ancestral single-queen condition. An extraordinary once in a lifetime present (Southern Hemisphere 2021-2022) bumper season has taught us ever new lessons. Bees really intent on swarming – even two-queen colonies – may do so irrespective of the beekeeping practices adopted.

The doubled versus the two-queen hive

Two distinctive types of multiple queen hives were discovered:

- hives where single-queen brood chambers are bridged with common honey storage supers; and

- hives where there are one or more extra queens in the same colony.

Until towards the end of the 19th Century, the conventional wisdom was that hives could only ever be operated with the one queen. Let’s hark back to the dawn of their discovery 140 years ago.

Firstly in April 1892 George Wellsvii from Aylesford, Kent reported successfully operating ‘doubled hives’. We can describe these sorts of hives as a line of (mostly two) single-queen hives capped with bridging honey supers (sometimes large single ‘coffin’ supers) over ‘excluder zinc’. These captured the early fruit tree blossom flow and powered into summer flora – presumably clover, brambles and hedgerow – producing ‘astounding amounts of honey’.

Then twenty five years later (1907) E.W. Alexanderviii from New York State and Craudhix from Ballyvarra, Ireland independently reported hives with ‘a plurality of queens’, the early progenitors of the two-queen hive. This is a more complex affair (two or more queens in the one hive) but they were variously designed to build bees to giant colonies by the commencement of the main flow (e.g. aster and goldenrod in the US) and in the UK and Southern Ireland (clover and the late heather flow).

We need not dwell on the detail or the long history of development of the seemingly impossible two-queen hive except to recall Alexander’s remarkable achievement of introducing ‘any number of queens’ to an already queenright hive. Ellis and Medicusx accounts of the late heather flow demonstrated that even the standard slow development of two-queen hives could greatly increase honey crops. These schemes reached an apogee in latter half of the 20th Century with the development of the Consolidated Brood Nest two-queen hive – the CBN hive – formulated by Floyd Moeller and John Hogg. Their schemes put all the brood together, all honey supers atop, mimicking single-queen hive operation.

The essential message is that all of these apiarists were able to generate colonies of extraordinary strength. Their hives produced rivers of honey.

The chastening reality was that maintaining the two queen condition was well beyond the skills of all but the most capable and dedicated beekeepers. The exceptional demand on attending to the needs of such colonies – building tower colonies or employing non standard gear, timing operations, taking off the crop and adapting to end of flow conditions – proved to be too much effort.

These requirements have been somewhat ameliorated. Any competent beekeeper can now run hives with an extra queen using standard gear, but it is important to realise that running such hives is, and will always be, a challenge of the first order.

Setting up and running hives with two queens

The doubled hive

The essential element of this scheme (using regular gear) is autumn preparation of contiguous single queen hives and the set up of straddled supers on or about the first day of spring (1 September in the Antipodes and 21-22 March in the Northern Hemisphere). Set up of doubled hives is like falling off a log. The provisos are autumn requeening, disease checks and close attention to optimising early spring nutrition. Two queens require double stores and double pollen input to build for the flow.

Here is a traditional scheme for running a doubled hive year round, good in principle but hard to achieve in practice.

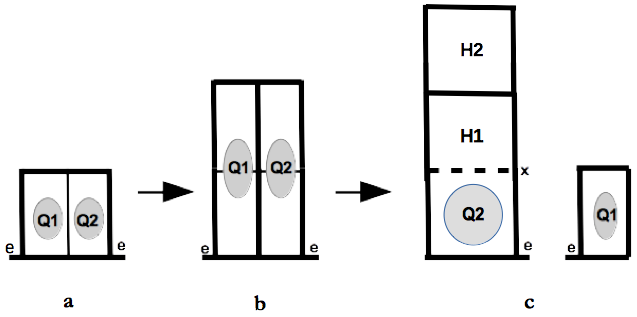

Traditional doubled hive scheme for honey production: e = entrance; x = excluder; Q1, Q2 = queens; H = honey supers:

(a) overwintered doubled – centrally divided – colony in early spring;

(b) colonies built to full ten or twelve-frame condition prior to main flow;

(c) colonies combined as a single-queen hive with sealed brood, and most of the bees are supered for the flow: the spare queen is offset to a nucleus hive.

A simpler and modern start up option is to run pairs of closely juxtaposed single-queen hives – prepared in autumn – rearranging them at the first opportunity in late winter or early spring here shown for an eight-frame set up. Larger nine, ten or eleven frame hives (such as the British National) can be overwintered a single story hive pairs.

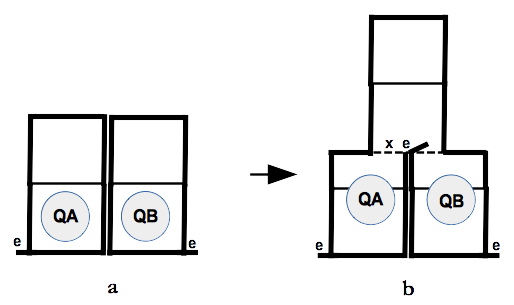

Modern doubled hive scheme for honey production: e = entrance; x = excluder; Q1, Q2 = queens; H = honey supers:

(a) overwintered pair of juxtaposed eight-frame hives prepared in autumn;

(b) double hive colonies united and reorganised in early spring using additional shallow brood boxes to allow queens to lay to maximum capacity.

The two-queen hive

Setting up and running two-queen hives is much akin to herding cats. Where there is a long lead-in time to the main flow – say an autumn heather flow – a second queen can be established as a nucleus above a division board (preferably a double screen) over a strong colony. Once well established the two colonies can be united by simply replacing the double screen with a queen excluder (or using a queen excluder and newspaper if a nuc/division board is used).

We often think back to the late 1960s and Robert Bankerxi running 1500-1600 two-queen hives and having another 1000 to 1200 nucs and packages to back up his operation as some measure of the challenge to running two-queen hives.

Here is a much simpler scheme we use for starting a two-queen hive, one that – like the doubled hive setup – gives bees an early start to achieve a crop on spring blossom flows. Note we run the two brood nests together so that – with brood below and honey supers atop – the hives can be run in the same way as single-queen hives are operated.

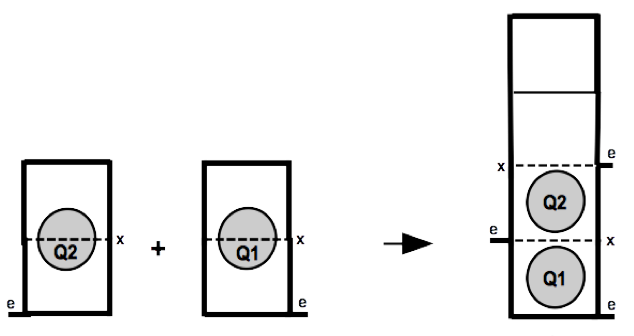

Two-queen hive system formed by uniting juxtaposed overwintered pair of hives to form an advanced Consolidated Brood Nest two-queen hive: e = entrance; x = excluder; Q1 and Q2 either an old queen and an introduced queen or two autumn-introduced queens: e = entrance; x = excluder; Q1, Q2 = queens:

(a) frames in each colony are sorted so that all unsealed brood is located in bottom brood chambers; and

(b) the colonies are united by piggybacking these overwintered doubles using newspaper to unite the colonies and an excluder to keep the queens apart.

Here are a couple of two-queen hives currently working Yellow Box (Eucalyptus melliodora) and Blakely’s Red Gum (Eucalyptus blakelyi).

Two of three hives working eucalypts in full cry at Hillside Station, Symonston, Australian Capital Territory 23 December 2021. Note offset support nucs.

Where to for multiple queen hive operation

While you may claim that operating colonies with extra queens on the prairie in Canada or in the best beekeeping locations in southeastern and southwestern Australia is a given, this is emphatically not the case. We have had some success and notable failures and we think we have a modicum of understanding of how such hives operate and why – in real time – they have sometimes failed. Commercial beekeepers we know ever only use them for seamless requeening operations.

Here is a notional hive condition trend predictor chart based on colony queen status. Note that outcomes such as nectar inflow can be temporally and locally condition dependent – a strong colony in a period of dearth may result in stores being consumed quite quickly when queens may also stop laying.

| Hive category | Number of laying queens | Population trend | Honey production potential | Swarming potential | Requeening trend |

| Non laying Queen | 0 | ꜜ | – | 0 | 0 → 0 |

| Single-Queen | 1 | ꜛ | + | ꜛꜛ | 1 → 1 |

| Doubled | 1 + 1 | ꜛ ꜛ | ++ | ꜛ | 2 → 1 |

| Two-Queen | 2 | ꜛꜛ | +++ | ꜛ | 2 → 1 |

Relative colony performance of colonies of different queen status

Getting a good honey crop off any hive is always a gamble, but good practice – and being able to build bees before the flow – makes some beekeepers using traditional single-queen hives more successful than others.

While doubled hives are easy to set up and run – as well as fix when they go awry – running two-queen hives is more akin to Russian roulette. Keeping control of queens and getting bees to super strength – especially for early flows is like starting all over again in beekeeping. The schemes we have outlined are at times nuanced, but we do owe it to British and American beekeepers for inventing the multi-queen hive.

We leave you with a famous early discussionxii between American Bee Journal editor Bud Cale and two-queen hive aficionado Clayton Farrar:

Cale: Isn’t your two-queen system of management too much work?

Farrar: If you are interested in getting those kind of crops, you will find a way to adapt yourself to the management.

Acknowledgements

We thank Lynne Ingram from Somerset Beekeepers’ Association and Richard Simpson from Devon Beekeepers’ Association for unstinted support and forum preparations.

Readings

iHoyle, E. (1741). According to Hoyle. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edmond_Hoyle

iiNatural History Museum of Los Angeles (2015). Invertebrate palaeontology. Apis henshawi Cockerell, 1907 (Henshaw’s honey bee). https://research.nhm.org/ip/Apis-henshawi/

iiiSeeley, T.D. and Morse, R.A. (1976). The nest of the honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) lnsectes Sociaux 23(4):495-512.

Seeley, T.D. (2010). Honeybee Democracy, 280 pp. Princeton University Press.

ivDemaree, G. (1892). How to prevent swarming. American Bee Journal 29(17):545-546. https://archive.org/details/sim_american-bee-journal_1892-04-21_29_17/page/544/mode/2up

vFarrar, C.L. (1968). Productive management of honey bee colonies. American Bee Journal 108(3):95-97,141-143. Republished as Farrar, C.L. (1968). Productive management of honey bee colonies. Apiacta 4:22-28. http://www.fiitea.org/cgi-bin/index.cgi?sid=&zone=cms&action=search&categ_id=55&search_ordine=descriere

viWade, A. (2021). A history of keeping and managing doubled and two-queen hives, 177pp. Northern Bee Books, West Yorkshire.

viiBritish Bee-Keepers’ Association Quarterly Converzatione (April 7, 1892). Report of meeting of 31 March 1892. British Bee Journal, Bee-Keepers’ Record and Adviser 20(511):132-133.

British Bee-Keepers’ Association Quarterly Converzatione (April 6, 1893).

British Bee Journal, Bee-Keepers’ Record and Adviser 21(563):126, 132-134. Editorial notices &c. (November 12, 1896). British Bee-Keepers’ Association Converzatione.

viiiAlexander, E.W. (September 1,1907). A plurality of queens without perforated zinc: How the queens are introduced: The advantages of the plural-queen system. Gleanings in Bee Culture 35(17):1136-1138.

ixCruadh (December 15, 1907). Plurality of queens: Another plan for introduction: Two or more queens to a colony. Gleanings in Bee Culture 35(24):1592-1593. https://www. biodiversitylibrary.org/item/74679#page/1608/mode/1up

xMedicus (February 10, February, 17 and February 24, 1910). A two-queen system: Some remarks on the adaptability for a heather district. British Bee Journal and Bee-Keepers’ Adviser 38(1442-1444):55-56; 64-66; 75-77. https://ia800301.us.archive.org/1/items/britishbeejourna1910lond/britishbeejourna1910lond.pdf

xiBanker, R. (1968). A two-queen method used in commercial operations. American Bee Journal 108(5):180-182. Republished as Banker R. (1968). A two-queen method used in commercial operations. Apiacta 2: 1-4. http://www.fiitea.org/cgi-bin/index.cgi?sid=&zone=cms&action=search&categ_id=53&search_ordine=descriere

Banker, R. (1979). Part B. Two-queen colony management in The Hive and the Honey Bee, Dadant & Sons, Hamilton, Illinois, Chapter XII, pp.404-410, 412.

xiiCale, G.H. (June 1952). The effect of the two-queen system on the harvest: An interview with Dr C.L. Farrar. American Bee Journal 92(6):236-237. https://archive.org/details/sim_american-bee-journal_1952-06_92_6/page/236/mode/2up