Alan Wade, Des Cannon and Dave Flanagan

In an unlikely tale of rivers of honey, we recently stumbled across two extraordinary beekeepers. One of them turned out to be Dave Flanagan, now a helpful author. These days he runs forty or so hives to pollinate almonds as a sideline business and says full time beekeeping as a way of making a living, and not living at home, is for the birds. The other beekeeper is Stringy Hughston of whom we know little except from some encounters by Des and from what Dave has told Alan about him.

Stringy ran an amazing enterprise, some 2400 tripled hives – hives with three queens each – on the Paroo River in the north western corner of New South Wales. Dave worked with him in the seasons of 1990 and 1991 so is well placed to relate the goings on in Stringy’s enterprise.

Doubled and Tripled Hives

Doubled and tripled hives are simply a row of single-queen hives supered over a common queen excluder or queen excluders. Gougeti is the only other beekeeper that we’ve found that has operated tripled hives though doubled hive setups are well known and stretch back to the early 1890sii. Here is a doubled hive (Figure 1) setup in Alan’s back yard early this spring.

F igure 1 Spring doubled hive set up: e = entrance; x = queen excluder; QA, QB = autumn introduced queens:

(a) colonies split and requeened on 8 March 2021; and

(b) doubled hive formed by newspapering hives together on 2 September 2021.

Ken Gray’s six-brood chamber hives working Wandoo eucalypt woodlandiii is another example of an apiary worked on the multiple queened hive principle. Bee historian Eva Crane records her encounter with Ken’s operationiv:

I saw multiple-queen hives in commercial use in Western Australia in 1967, that extended horizontally, instead of vertically as skyscrapers do; they were called coffin hives. The unit consisted of a row of six 8-frame Langstroth brood boxes, separated by dividers, their flight entrances facing alternately to either side of the row. A single super (honey-storage chamber), holding 50 frames, extended across all six brood boxes, each of which had its own queen excluder.

Alternatively a three-decker outfit was used, with a row of six separate honey supers below the 50-frame super…

The Paroo Triples

In researching doubled and multiple queened hives, Alan got to chatting to New South Wales queen breeder Frank Malfroy. He told Alan about Dave Flanagan having worked with Stringy in the early 1990s using tripled queen hives.

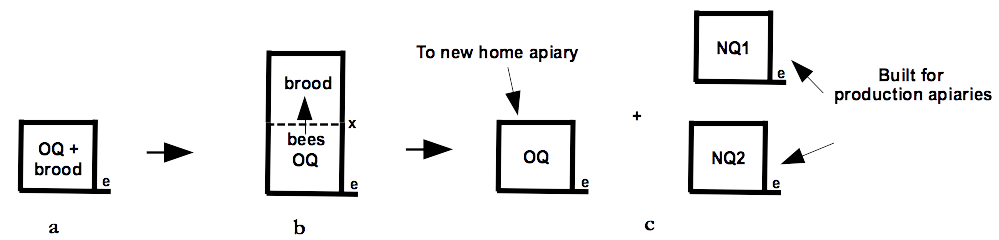

Stringy’s operation comprised around 7200 (2400 tripled) ten frame working brood chambers. This required a centralised backup apiary, needed to provide a steady and ready supply of building and replacement brood chambers. These hives were generated by splitting strong ten frame colonies and introducing a caged queen to each new colony (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Single hive establishment: e = entrance, x = excluder, OQ = old queen; NQ = new queen:

(a) strong colony;

(b) bees were shaken into empty super, brood and stores moved up; and

(c) brood, stores and bees distributed and caged queen introduced to each split.

The scale of this nursery operation is reflected in Des’s first recollection of meeting Stringy:

I watched him once at a Tocal beekeeping field day demonstrating how he used a post hole auger on a tractor to mix sugar syrup and pollen patties. That was the first time I met him.

The main apiary operation was spread some ninety kilometres upstream and a further ninety kilometres downstream of the tiny town of Wanaaring (population 49) in New South Wales Channel Country. Each apiary pod comprised 120 hive pallets, two tripled hives to the pallet. All up we’ve calculated there must have been ten apiary sites each running 240 tripled hives powered by 7200 queens. Each colony was dynamically managed for both for honey production and for regular brood box replacement.

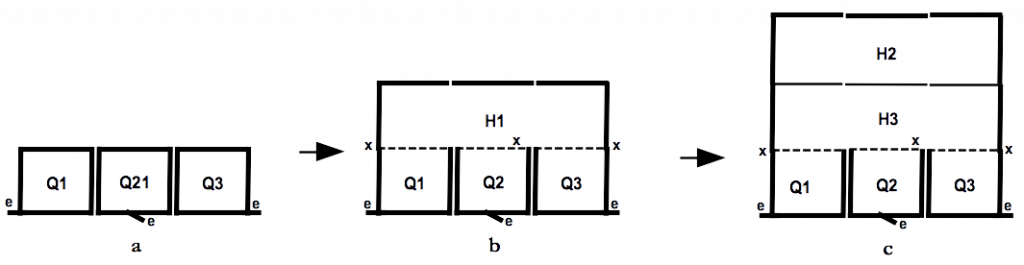

The essential set up was that of three single-queen single ten frame colonies strapped together (Figure 3). These were constituted as tripled hives by addition of thirty five frame full depth coffin supers over excluders united using the normal newspaper method. The coffin supers were dynamically managed using standard under-supering and blower techniques to remove bees from honey supers.

Figure 3 Coffin hive setup and operation: e = entrance, x = excluder, Q = queen; H = honey excluder:

(a) three single-queen ten-frame colonies strapped together,

(b) triple queen hive established by papering on a 35 frame coffin hive; and

(c) each tripled hive operated dynamically by under-supering and progressively removing fully capped honey honey supers.

The Harvest

Dave did not really have anything to do with the honey extraction plant in Wanaaring. His job was to cart away extracted stickies, work the floodplain apiaries on regular five-day round trips and bring back as many coffin hives filled with honey as quickly and efficiently as possible (Figure 4). Dave tells us that Stringy employed as many in the town who were willing to work in the honey extraction plant. Perhaps one clue as to the scale of the operation is reflected in another of Des’s recollections:

I didn’t know Dave Flanagan but did know Stringy Hughston quite well. The last time I saw Stringy was at the Capilano factory at St Marys: he was 86 and had just driven a semi load of honey down from Wanaaring. He told me at one stage the reason he went to the big 35 frame supers was so that he could use a machine loader to lift them off, figuring it was better OHS [occupational health and safety] wise or words to that effect. I don’t think OHS existed as an acronym at the time.

Figure 4 Dave Flanagan transporting coffin hives on the Paroo River New South Wales in 1990.

Photo: Dave Flanagan

Des also relates a story about Stringy that tells us that his life was not entirely devoted to bees:

I must also relate a very funny story about the NSW Conference in 1998 when we shaved his new beard (the first time he ever grew one) off with electric horse clippers to raise money for charity – the humour was in what he did when we squirted tomato sauce over his front to make out that we had cut his throat. He knew we were going to do it in advance, and jumped off the stage yelling we had cut his throat, and it was worse than The Man from Ironbark. We had to chase him around the conference dinner and drag him back screaming. His poor wife thought we had cut his throat and almost fainted.

After this, maybe you are wondering how on earth anyone except a tall tale teller might have got a name like Stringy. In Des’s words:

I also found out indirectly how he got his nickname when my truck broke down near Bemboka, and the local garage organised a lift home with a tyre distributor. This guy asked me if I knew Stringy, and said that he (the tyre guy) had carted semi loads of honey tins out of a Stringybark flow in Tumut in 1952, and that Stan Hughston had made so much honey on that flow that he was known as ‘Stringy’ ever after.

On hearing this tale, Dave Flanagan responded by telling Alan it was wet that year – most of southeastern Australia experienced once in a century floods in the early 1950s – and that most beekeepers left the area. But of course Stringy stayed and got ten 60lb tins of honey per hive. That was an amazing amount of honey and anyway, despite the fact that Stringy was running single-queen hives at that time, the name stuck for a lifetime.

As parting thought you might ask why anyone would bother running a hive with more than one queen. John Holzberleinv signals that for not too dissimilar two-queen hives, and for about 50% more work with a similar amount of gear, one can obtain the same amount of honey as a beekeeper running double the number of hives:

The two-queen system develops a higher degree of efficiency, since the larger the population the more honey is stored per bee. It permits the operation of large colonies without the danger from swarming that results when single-queen colonies are permitted to attain large populations before the honey flow begins.

The reality is of course that you need some beekeeping acumen to run hives with an extra queen and that their operation is really only suited to exceptionally productive or permanent apiary sites. That doubled or tripled hives are more or less swarm proof is signalled by the fact that failure of a queen does not result in the queen in that chamber being superseded. That unit simply fails entirely as the queen pheromone titre from any remaining queens mitigates against queen replacement.

And a disclaimer: Northern Bee Books in West Yorkshire have just published a book by Alan on doubled and two-queen hivesvi. It provides more details of Stringy’s Paroo River venture and about ways beekeepers can get a whole lot more honey out of their bees.

Readings

iGouget, C.W. (July 1953). The three-queen pyramid. Gleanings in Bee Culture 81(7):395-398. https://archive.org/details/sim_gleanings-in-bee-culture_1953-07_81_7/page/394/mode/2up

iiWells. G. (1894). Guidebook pamphlet on the two-queen system of bee keeping. G.F. Gay. Snodland Steam Printing Works, Malling Road, 15pp. Facsimile copy can be found at Wade, A. loc cit.

iiiEva Crane Gallery (1967) ECT-1096: Australia. Ken Grey’s coffin hive in Wandoo woodland. https://www.evacranetrust.org/gallery/australia ECT-1096: Australia

ivCrane, E. (1980). Multiple queen hives and hyper hives in Perspectives in World Agriculture: Apiculture, Chapter 10. pp.261-294. Farnham Royal, UK: Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux. https://www.evacranetrust.org/uploads/document/b00fb1cb4f88f874217e28dcf04930fb5639e1bd.pdf

vHolzberlein, J.W. (1955). Some whys and hows of two-queen management. Gleanings in Bee Culture 83(6):344-347. https://archive.org/details/sim_gleanings-in-beeculture_1955-06_83_6/page/344/mode/2up

viWade, A. (2021). A history of keeping and managing doubled and two-queen hives, 176pp. Northern Bee Books, Scout Bottom Farm, Mytholmroyd, West Yorkshire HX7 5JS. https://www.northernbeebooks.co.uk/?s=wade