Alan Wade

In the two previous blogs we’ve visited autumn closedown. Trouble is this year, any boxes of stickies that have been put back on hives for clean up were promptly refilled. Take the illustrated hive at an apiary down the road from the Jerrabomberra Wetlands. The top two supers were full to the gills in late February. So off the two supers came for winter. By late March we returned with the intention of feeding the colony, but an autumn apple box flow had done the job for us. With a full super of honey, a healthy hive and a young queen, the bees should now easily get through to spring.

Removing gear for overwintering at a Narrabundah Lane Apiary – Photos: Alan Wade

So as we are moving into winter there is little we or the bees can do to improve their lot. That is, of course, apart from the bees taking their occasional cleansing flight in warm spells and our doing the occasional check to make sure hive entrances remain clear. Now the bees have turned their attention to optimising their intrinsic internal hive condition and are doing their best to insulate themselves from the impending cold and wet outside.

Bees do actually slow down not shut down

Unlike bears in northern hemisphere winters and unlike crocodiles buried in black soil mud flats of Kakadu’s dry, honey bees don’t hibernate. But both worker bees and their queen do a fair approximation to ‘closing down’ in that they conserve stores and are largely freed of the task of raising bees. Consequently their lives are greatly extended.

With an also good autumn pollen flow, emerging bees have already maxed out on their protein intake. These long-lived (diutinous) bees will, like the colony, nearly all make it right through till spring. During your autumn inspection you cannot have failed but to notice pollen stored in frames located at the margin of the brood nest. That store is the bee’s elixir of life, a veritable treasure:

Eat what you can; and

Can what you can’t.

But to say that bees simply slow down is an oversimplification. Firstly at the commencement of winter honey bee colonies down regulate numbers to minimise the chance of running out of stores, that is face starvation. Any worn out field bees still around are deemed not worth rescuing and will soon disappear as keeping them would deplete precious colony stores. However young bees are essential to keep the colony operating over winter and their importance to the colony cannot be overemphasised. Secondly the bees themselves need to be in good general disease free condition and must have a good queen capable of laying as many workers as the colony will need to raise brood and collect top-up stores coming into spring.

The take home message is that by now you should have done a disease and brood pattern check and made sure there were plenty of stores. Calls for ways to feed bees in winter is a recurring club Beginner’s Corner theme but bees are ill-equipped to process artificial supplements after Anzac Day and disturbing hives in winter is very stressful. As we shall see, hive supplementary winter feeding can and may need to be undertaken, the better plan is have the stores already in place.

More on the storing instinct

European honey bees have evolved to store all their needs in a remarkably short window of opportunity – brief intense honey flows. In all but the lower alps and parts of Tasmania, this is by no means obvious in Australia. By and large our bee seasons are long and are characterised by extended long honey flows mainly associated with eucalypts. This is a global anomaly as is our Varroa free status.

In contrast northern European and the far northern Americas both bees and beekeepers work to a very tight timetable. All temperate bee colonies, even in Australia, must build quickly at winter’s close to take advantage of early-to-mid spring honey flows. Then, left alone and all other things being equal, they will swarm to produce at least one new colony. The bees must then go on to rebuild stores to end up where bees are now, well provisioned and able to hang in over winter.

Horses for courses

Middle Eastern and African races of the Western Honey Bee (Apis mellifera) have evolved under very different environmental conditions. They have adopted entirely different strategies for surviving periods of extended dearth. For example, some African Apis mellifera races and at least one of several Giant Honey Bee species, Apis dorsata, migrate over vast distances, sometimes bivouacking to chase known or likely floral oases in preference to putting away large stores of honey and pollen. Many races of both the Western and Asian Honey Bee, as well as all the other Apis species of honey bees, are known to swarm profligately and most frequently abscond when conditions deteriorate. Hence, with the possible exception of one of the two dwarf honey bee species, Apis florea, no other honey bee has shown any potential for domestication.

The eight of so honey bee species in existence are all of tropical origin. European races of the Western Honey Bee we keep (cold climate adapted Apis mellifera) – as well as some temperate Asian Honey Bee races (northern Apis cerana) – have radiated north. To do this successfully they have adapted by squirreling stores and staying put over winter.

The honey bee queen in winter

A primary function of any colony is to protect its queen year round, a tall order for a colony hell bent on fending off the ever present risks of starvation, predation and disease. Almost always the queen will be almost the last bee to survive in a dwindling colony.

Maintaining a core of warm bees throughout winter is essential not least to ensure the survival of the queen and sufficient bees to kickstart colonies un late winter. However the optimal 34-350 brood nest temperature is lowered when the colony undergoes periods of broodlessness to conserve stores. Möbus and many others have demonstrated that new bees will be raised intermittently during periods of dearth, particularly in late winter. Sub-optimal thermal regulation results in brood chilling and high mortality particularly at the margin of the brood nest. Such stress is a particularly prevalent feature of Chalkbrood disease outbreaks.

Lessons from the tree hollow

Let’s examine bees occupying a tree hollow. Bees in the wild have have a distinct preference for a tree hollow (or rock cavity) sealed at the top with a restricted bottom entrance. A swarm entering such a cavity commences to build comb in the warmest spot – the roof – insulated above by a large amount of wood or rock. After 21 days, from the time the queen commences laying, the first cohort of worker bees emerge. This comb, then filled with honey, acts as an additional thermal blanket. Gradually the colony extends downwards all the time storing honey above and some stores (honey and pollen) at the periphery of the nest. These lateral stores provision new and emerging brood while the honey larder above helps make swarming and eventual overwintering possible.

The whole downwards development process is reversed any time from late summer, that is once stores are consumed faster than nectar can be gathered. From then on bee numbers not only decline, but they also consume rather than gather honey. Meanwhile the brood nest – the engine house of the colony – moves upwards. Supplementary stores may be gathered in brief periods when it is warm enough and winter flowering resources are available but this simply does not occur in northern Europe where the bees evolved. Victor Croker and David Leemhuis made this observation very pointedly during the Jerrabomberra Field Day on the 17th of March: they found fresh nectar in the brood nest but no evidence of storage in the upper honey super.

It is worth noting that mid-year flows are not uncommon in coastal southeastern Australia, notably on winter flowering Spotted Gum (Corymbia maculata) but such flows with large brood nests are always at risk brood chilling. This can occur with the arrival of cold nights or under wet humid conditions when nectar is difficult to process, when fermentation can occur. In our southern highlands climate, bee shut up shop.

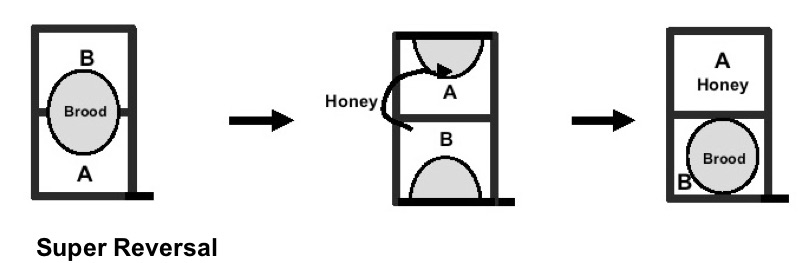

In Langstroth hive management, double brood boxes are routinely reversed in preparation for winter so that most brood is in the bottom box while spare honey is moved upstairs both to make room for the queen to lay and to insulate the space above the brood nest. Highly insulated and Warré hives are notable for surviving even with small bee clusters and limited stores.

Note it is now too late to undertake this manipulation unless you are working bees in a protected sunny location at the coast.

At our Jerrabomberra Wetlands apiary, we have tried to remove as many surplus supers as possible to avoid leaving bees to heat over-sized MacMansions. The recent prolonged and late honey flow has made this task difficult at the Jerrabomberra Wetlands apiary despite the club effort to remove the main honey crop.

Insulation and ventilation

Bees are ectothermic poikilotherms. By that we mean they adopt the temperature of their surrounding environment. But they must also work to maintain an almost constant brood nest temperature of 33-36 0C – typically close to 34 0C – year round. Pupae are particularly sensitive to temperature excursions though the winter cluster temperature is lowered slightly in periods of broodlessness.

There is emerging evidence not only that bees move freely and consume less honey in well-insulated hives but that humidity and water balance factors are also better handled. Infra-red cameras, along with thermistors deployed inside hives, are now showing that conventional wooden and plastic hive walls irradiate large amounts of heat in winter putting nutritional and thermal stress on bees – see Derek Mitchell under Readings. Victor Croker and David Leemhuis from Australian Honeybee only operate highly insulated hives They have virtually eliminated Nosema Disease as well as brood chill-linked Chalkbrood. Bees certainly work longer hours and under more extreme conditions in insulated hives. Next time you come out early to the Jerrabomberra wetland apiary check out which hives entrances are the busiest: the insulated hives are usually the first to start up..

Simple insulated cover used by club member Peter McKeahnie for insulating his wooden Langstroth hives – left detail of cabinet structure, right cover in place with hive entrance space provision – Photos: Peter McKeahnie

It is important to realise that minimising thermal losses is not the only factor in optimising overwintering colony condition. Bernard Möbus (see readings) not only opened hives in snowbound conditions to investigate intermittent brood raising over winter, but also installed mini-anemometers to investigate air flow patterns. He concluded that honey – stored in upper hive comb maintaining a single Langstroth space (~9 mm) between frames – restricted air flow and optimised its insulating value. He also observed that the double Langstroth spacing maintained between brood frames serves several purposes. It allows nurse bees to operate on facing combs, it allows bees to cluster more densely and – in the absence of overly large numbers of bees – it facilitates free air movement to remove carbon dioxide and heat during periods of active brood rearing. He also found that the air circulation pattern is up and down, not across, combs and that CO2-rich air is vented from the base of hives.

Our new Ulster Observation – Left hive just loaded with bees and right now with insulated Derwent Cover shutting out cold nights

From all these findings we conclude that the two revolutionary discoveries in hive design in the early 21st Century have been the invention of the screened bottom board and insulated wall and lid hive.

In the upcoming winter months we will reflect more on bee biology basics than on actual beekeeping practice. One topic that we often give scant attention to is the field interaction of insects with flowers, something of interest to our Native Bee Special Interest Group run by Peter Abbott and to the value we place on honey bee pollination. While the value of this service to orchards and horticulture is well recognised, to say that honey bees are good for the environment is a maxim we need to question. Bees also pollinate weeds – a valuable resource to beekeepers – but that are a menace to farmers, gardeners and the natural environment. They do complete with native birds and insects for floral resources, many of which also provide specialised pollination services.

A weed ecologist colleague of ours has noted that birds are a primary vector of fruit bearing woody weeds seed dispersal: think olives, asparagus fern, wild passionfruit, pecans and exotic palms. He wryly observes that one of the solutions to preventing spread of weeds is to ‘shoot the birds’. We might ask him if a simpler solution might be to ‘poison the bees’. But life is more complex than that and we may have him along to speak to the club. We live in a complex and much modified world and Homo sapiens, as an ecotone (forest-edge dwelling) species, has come to live with and very much depend on honey bees.

Readings

Mitchell, D. (2016). Ratios of colony mass to thermal conductance of tree and manmade nest enclosures of Apis mellifera: implications for survival, clustering, humidity regulation and Varroa destructor. International Journal of Biometereology 60: 629-638. https://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&pid=forums&srcid=MTQ1OTYwMzIwNzQ2NzIzNDE4MDcBMDc3NDA4MjkyOTA0MTMzNTYzMDUBUjE0WWxzVU9BZ0FKATAuMS4xAQF2Mg

See also Honeybee colony thermoregulation at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2813292/

Möbus, B. (1998). Brood rearing in the winter cluster, Part I. American Bee Journal 138(7): 511-514. http://polyhive.co.uk/recourses/mobus-bernard-his-work-on-swarming-and-wintering/brood-rearing-in-the-winter-cluster/

Möbus, B. (1998). Brood rearing in the winter cluster, Part 11. American Bee Journal 138(8): 587-591.

Möbus, B. (1998). Brood rearing in the winter cluster, Part III. Damp, condensation and ventilation American Bee Journal.

Parts II and III http://poly-hive.co.uk/recourses/mobus-bernard-his-work-on-swarming-andwintering/ damp-condensation-and-ventilation/

Be the first to comment